By Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

Soviet influence at Voice of America during World War II – documents and analysis

Soviet influence at WWII Voice of America

From VOA to communist regime journalist

Choices of VOA’s pro-Soviet journalist

VOA journalist marries Communists

A pro-Soviet propagandist at OWI and VOA

VOA communist partner Stefan Arski

Pro-Soviet collaborators at OWI and VOA

A VOA friend of Stalin Peace Prize winner

Among Soviet sympathizers at VOA

Critics of her communist influence at VOA

Was she VOA’s communist ‘Mata Hari’?

Mira Złotowska, later known as Mira Michałowska, who published books and articles in English as Mira Michal and used several other pen names, was one of many radically left-wing journalists who, during World War II, worked in New York on Voice of America (VOA) U.S. government anti-Nazi radio broadcasts but also helping to spread Soviet propaganda and censoring news about Stalin’s atrocities. While not the most important among pro-Soviet propagandists at the Voice of America during the war, Michałowska later went back to Poland, married a high-level communist diplomat, and for many years supported the regime in Warsaw with soft propaganda in the West while also helping to expose Polish readers to American culture through her magazine articles and translations of American authors. One of the American writers she translated was her former VOA colleague and friend, the 1953 Stalin Peace Prize winner Howard Fast, who in 1943 played an important role as VOA’s chief news writer. Despite today’s Russian attempts to undermine journalism with disinformation, the Voice of America has never officially acknowledged its mistakes in allowing pro-Soviet propagandists to take control of its programs for several years during World War II. Eventually, under pressure from congressional and other critics, the Voice of America was reformed in the early 1950s and contributed to the fall of communism in East-Central Europe.

A misguided supporter?

Working for the Voice of America during World War II, Mira Złotowska, later better known as Mira Michałowska, helped in a minor way to impose Soviet communism on Poland. In the post-war years, she served the communist regime for several decades as a journalist, television consultant, and wife of a prominent regime ambassador. The most serious charge against Mira Michałowska of alleged spying on an American diplomat cannot be proven beyond all reasonable doubt. Still, it is consistent with other confirmed information about her background and activities as a journalist, writer, and supporter of communism and the Soviet Union. While in the United States, both Złotowska and Stefan Arski, her Voice of America colleague, were in contact with Bolesław (Bill) Gebert, a Communist Party USA organizer who was identified in Soviet intelligence cables deciphered through the U.S. Venona project as actively assisting the KGB. Gebert’s KGB cover name was “Ataman.” Złotowska and Arski were also in contact with Professor Oskar R. Lange, who was presented in Venona KGB cables as an agent of influence under the cover name “Friend.”1

Lange, a naturalized American citizen and professor of economics at the University of Chicago, traveled in 1944 with approval from President Roosevelt for a meeting with Stalin in Moscow. Arski listed Lange as one of his references on his U.S. government job application. After the war, Lange renounced his American citizenship and became the Warsaw regime’s first ambassador to Washington. Gebert became the regime’s ambassador to Turkey. It is possible that through her close links with individuals who already worked as KGB intelligence agents or agents of influence, Złotowska was recruited after the war as a spy or an informant, but there is no definite proof. Some contact or cooperation with the communist security and intelligence services would not be unusual since the regime regarded all important journalists, diplomats, and even their family members as potential spies and informants. Regime ambassadors Lange and Gebert were former wartime KGB intelligence assets if not actual agents. Gebert was identified as receiving money from the KGB.

The communist regime in post-war Poland could offer substantial rewards to diplomats, writers, artists, and journalists who chose to support it. It also had the power to intimidate, punish, and blackmail those who did not. As it turned out later, a few Voice of America Polish Service journalists had been listed as secret police informants while they were still living in Poland. They were most likely forced to cooperate; some had stopped these contacts before leaving Poland for the West. Some are known to have resisted providing any useful information. Blackmail by those who had the power over job promotions, foreign travel, admittance to universities, publishing articles and books, and access to scarce consumer goods was a part of daily life in Poland under communism.

Unlike most people in Poland, Mira Michałowska was not forced to cooperate with the regime to survive; she did it willingly, using her outstanding talents and skills. Whether Michałowska honestly believed in Soviet communism while working to support the Polish regime is not clear. What may have been at first youthful idealism turned later into self-serving rationalization that what she was doing was right because other supporters of the regime would have behaved much worse if they were in her position, and that she could still do some good. She later identified herself with reform-minded Polish communists who claimed to be interested in improving relations with the United States and Western Europe. She worked hard to win support for the communist government among Western publics, journalists, and diplomats. She also enjoyed all the privileges of the communist elite. She did not seem to be willing to give them up for the sake of presenting the whole truth, which she would not have been able to voice publicly or publish officially in Poland. She was comfortable practicing journalism based on half-truths.

One example of this type of journalism was her article written for Harper’s Magazine in 1946. Złotowska wrote about a regime militiaman in Poland who was presented as a staunch defender of the rule of law. “We are not a nation of criminals,” she quoted the communist militiaman telling a Polish peasant that even Nazi criminals deserved a fair trial.2 At the time, local Communists, with the help from the Soviet NKVD, were already imposing a harsh dictatorial regime in Poland, falsely accusing former anti-Nazi fighters of being fascists, arresting and torturing their political opponents and condemning them to death with fake evidence. One of the victims was 17 years old Danuta Siedzikówna, alias Inka, a former nurse in the anti-Nazi Polish underground army during the German occupation, who, after the war, joined a small group of armed anti-communist partisans as a medic. After the Soviet attack on Poland in 1939, her father was arrested by the NKVD and deported to Russia. He joined General Władysław Anders’s Polish Army and left the Soviet Union with his unit but died in Iran in 1943. The German Gestapo in Poland executed her mother in 1943. A few months before Złotowska published her article in Harper’s magazine praising the communist justice system, Siedzikówna was arrested and tortured by the UB communist secret police, sentenced to death by a military court in Gdańsk, and executed on August 28, 1946. From 1944 to 1956, the communist authorities in Poland arrested approximately 300,000 persons. The Soviet NKVD arrested and deported to Siberia thousands of former Polish anti-Nazi underground Home Army fighters. Communist courts sentenced thousands more to long-term imprisonment. The majority of the 6,000 death sentences during that period were carried out. Special legislation allowed trials of non-military individuals before military tribunals, including young people and children. Danuta Siedzikówna was executed in a Gdańsk prison six days before her 18th birthday.3 The price of obscuring the truth was ultimately much higher for the Western public misled by pro-communist propaganda and for the people in Poland than the potential consequences of honest news reporting about Soviet and Polish communist human rights abuses would have been during and immediately after World War II when the Voice of America covered up such crimes.

Spying accusations

What makes Mira Złotowska-Mira Michałowka’s later life story even more sensational in this historical context are her propaganda activities in the United States after the war and her alleged but not proven spying for the Warsaw regime. She returned to America in the 1960s as the wife of the Polish People’s Republic ambassador and became an active diplomatic hostess in New York and Washington. She was described in an article inserted by a member of Congress in the Congressional Record in 1968 as “a thoroughly modern Mata Hari,” a reference to the famous courtesan who was executed in France during World War I on charges of spying for Germany.4 Whether she was spying or not, she was definitely involved in the ultimately unsuccessful business of trying to split the Polish-American community. She and her diplomat husband failed to get significant support for the regime among Polish and non-Polish Americans. Polish-American organizations were not opposed to more academic and cultural exchanges between Poland and the United States or American loans and business investments in Poland as long as they were done under careful management and monitoring to ensure that they would benefit mostly the people in Poland rather than the regime. Under no circumstances would most Polish-American civic leaders agree to give legitimacy by any of their actions to the communist regime. There were a few more exceptions to this rule among Polish-American businessmen, but even most of them showed no excessive support for the communists in Warsaw.

The “Untouchable” Parade

HON. JOHN R. RARICK

OF LOUISIANA

IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

Thursday, February 8, 1968

Mr. RARICK. Mr. Speaker, just as the Red Vietcong were able to infiltrate South Vietnam and on New Year’s Day rise to the surface In a suicidal battle against the citizens, we can better appreciate the constant threat from the American Vietcong, the “Untouchables” who are planted in our country—in our Government.

Mr. Capell’s “Untouchables, Part VII” should be revolting enough to awaken every patriotic American—liberal, moderate, or conservative—to demand action for removal of these undesirable untouchables.

The President of the United States must appreciate the danger from Madam Jerzy Michalowski, wife of the current Polish Ambassador to the United States and stationed here in Washington, D.C. the nerve center of our Republic.

Her removal needs only that President Johnson declare her husband, Ambassador Michalowski, persona non grata. Why doesn’t he do it?

Mr. Speaker, under unanimous consent I follow my remarks with “Untouchables, Part VII from the Herald of Freedom and a clipping from the Government Employees Exchange here in the District of Columbia dated February 7:

[From the Herald of Freedom, Feb. 9, 1968] THE UNTOUCHABLES—VII

Now emerging as possibility more than an innocent and duped bystander in the Warsaw Spy and Sex Scandals is the American Ambassador to Poland at that time, Jacob D. Beam. The Government Employees’ EXCHANGE, a liberal bi-weekly dedicated to civil service reform, owned and edited by Mr. Sidney Goldberg, carried a story concerning Beam’s involvement in its January 10, 1968 issue. Under the red headline, “Sex Scandals Involve Beam,” the story stated that Madam Jerzy Michalowski a Communist agent, “has been positively identified as ‘one of the chief architects of the ‘Warsaw Sex and Spy Scandals'” which disrupted the American Embassy in Warsaw during the incumbency of Ambassador Jacob Beam. . . . In addition, the informant stated the woman has also been identified ‘without any question of doubt’ as having maintained an ‘intimate personal relationship’ with Mr. Beam from 1957 to 1961. . . .”

U.S. Congressman who inserted accusations against Ambassador Beam and Mira Michałowska into the Congressional Record was ultra-conservative, strongly anti-Soviet and anti-communist Democrat from Louisiana Rep. John R. Rarick, a decorated World War II veteran but also a segregationist. He did not want Beam to be U.S. Ambassador to Moscow and, in 1969, repeated his warnings on the floor of the House of Representatives about Beam’s alleged romantic relationship with Mrs. Michałowska.5

President Johnson ignored Rarick’s warnings and did not declare Ambassador Michałowski persona non grata, which would have also meant the expulsion of his wife from the United States. But while Rarick was a far-right, anti-integration Democrat and could be dismissed as making irresponsible accusations, over the years, many other members of Congress, both moderate Republicans and moderate Democrats, spoke up during World War II and in the late 1940s and the early 1950s against the danger of Soviet influence and propaganda in Voice of America programs and their initial ineffectiveness behind the Iron Curtain. In a speech on the floor of the House of Representatives on July 24, 1951, Congressman Richard B. Wigglesworth (R-MA), a future U.S. ambassador to Canada, read excerpts from letters from listeners to Voice of America programs in Poland. Six years after World War II had ended, radio listeners in Poland still described VOA programs as “uninteresting, drab, bureaucratic in tone, unconvincing.” Some of the legacy of Złotowska and Arski’s presence lingered at the Voice of America Polish Service for several years after their departure. It took pressure from Congress and the replacement of the entire World War II Polish Service staff with new anti-communist journalists to eliminate the tendency to protect Russian interests.

Rumors of affair with U.S. Ambassador

As can be seen in the 1968 Congressional Record, Mira Michałowska was described following her return to the United States as leading “a very busy life” and “being glamorized as a Washington hostess.” Her ability to manipulate U.S. government officials and members of Congress into offering more support for the communist regime in Warsaw and limiting or eliminating support for Radio Free Europe and dissidents behind the Iron Curtain was probably a more real danger to Americans than any possible spying activities. Besides her possible influence over Ambassador Beam, she did not appear successful.

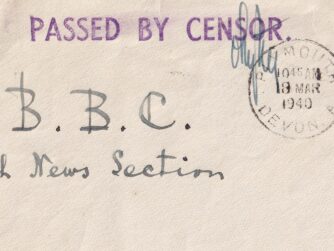

In her “Between the Lines” column, quoted in the Congressional Record, American newspaper commentator Edith Kermit Roosevelt described Michałowska as “a Warsaw charmer” whose “various marriages” and activities “may provide the incentive that could force the issue of Communist espionage and policy manipulation into the limelight.” Edith Kermit Roosevelt noted that White House and State Department circles remained silent about Ambassador Beam and Mrs. Michałowska. She reported being told that they feared that “the revelations could spark ‘a new wave of McCarthyism in the United States.'” In 1967, the columnist asked the National Archives in a letter for information about Stefan Arski’s OWI personnel records. She received a reply that there were no records for Stefan Arski. She and presumably the National Archives staff did not know that his OWI personnel records were under the name of Artur Salman, his real and legal name. Edith Kermit Roosevelt was a granddaughter of President Theodor Roosevelt and former wife of VOA Russian Service chief, ex-Soviet military intelligence service general Alexander Barmine, who had defected to the West in 1937 and became an American citizen. Barmine named to the FBI and congressional investigative committees two high-ranking officials of the Office of War Information (OWI)—the wartime parent agency of the Voice of America—as potential Russian spies and actual agents of influence, but he could not provide proof they were involved in spying for the Soviet Union. He and Edith Kermit Roosevelt had a bitter divorce after four years of marriage.6

The American columnist was hinting at rumors that Mira Michałowska became romantically involved with the U.S. Ambassador to Poland, Jacob D. Beam. It was feared among American intelligence circles that Ambassador Beam may have inadvertently helped Michałowska get information that allowed the communist counterintelligence service to unmask an important CIA agent in the Polish regime’s security apparatus, causing the agent, Michał Goleniewski, to flee to the West. Goleniewski had helped the CIA and the British intelligence service MI5 identify several Soviet spies. Still, some years after he had sought asylum in the United States, he embarrassed his American CIA handlers with his claim that he was Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich, who was saved from the Bolshevik execution of the Russian imperial family members.

Allegations against Mira Michałowska that she may have helped put Goleniewski in danger of arrest were never confirmed and may or may not be true. The information that led to his escape from Poland may have come from a Soviet mole in Britain. There is also no proof that Michałowska’s first nuclear scientist husband did any spying for the Soviet Union on U.S. atomic secrets. Likewise, there is no proof that Michałowska had anything to do with Irvin C. Scarbeck‘s sex scandal at the U.S. Embassy in Warsaw. Scarbeck was a State Department official convicted in 1961 of giving information to the Polish secret police after he had become involved with a Polish woman and was blackmailed by Polish intelligence agents. But quite possibly under the influence of charming and persuasive Mrs. Michałowska, U.S. Ambassador to Warsaw Jacob Beam became a severe critic of the Polish Service of Radio Free Europe and started to demand that it be closed down for doing damage to U.S. relations with the communist government in Poland.

Vice President Richard Nixon, who was greatly impressed by the enthusiastic reception he got on his 1959 visit to Warsaw from ordinary Polish people who had learned about the route of his motorcade from Radio Free Europe Polish broadcasts, reportedly told Ambassador Beam to stop his anti-RFE campaign, explaining to him that it was also “an American diplomat’s responsibility to maintain a close relationship with the people.”7

Ambassador Beam eventually broke off his relationship, whatever it was, with Michałowska and put the sex-spy scandal behind him. He was named U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union and eventually became a strong supporter of Radio Free Europe, serving as chairman of the RFE board.

VOA broadcasts to Poland were drastically reformed in the early 1950s when new journalists, including Zofia Korbońska, an anti-Nazi World War II fighter who had escaped arrest by communists and Soviet NKVD in Poland, were brought in to replace the previously pro-Soviet staff. She was hired in 1948 at the recommendation of former Ambassador to Poland Arthur Bliss Lane. As Zofia Korbońska and her husband, Stefan Korboński, were fleeing Poland in 1947, hidden below the deck of a ship bound for Sweden, Mrs. Michałowska was free to travel without fear between Poland and Britain as the wife of a loyal communist diplomat. Another refugee journalist from Poland who had worked at both Radio Free Europe and the Voice of America was Marek Walicki. He crossed two heavily guarded borders and found his way to Munich, West Germany, where, in 1952, he became the youngest broadcaster working in the RFE Polish Service. The regime eventually turned against Mrs. Michałowska and her husband. Jerzy Michałowski retired early from the diplomatic service two years after the anti-Semitic campaign initiated by hardline Communist Party leaders in 1968.

Ted Lipien was Voice of America’s acting associate director in charge of central news programs before his retirement in 2006. In the 1970s, he worked as a broadcaster in the VOA Polish Service and was the service chief and foreign correspondent in the 1980s during Solidarity’s struggle for democracy in Poland.

NOTES:

- John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999) 234-235.

- Mira Złotowska, “I came back from Poland, Harper’s, November 1946, https://harpers.org/author/mirazlotowska/.

- Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, “Otwarcie wystawy „Zbrodnie w majestacie prawa 1944–1956” – Kraków, 2 lutego 2006 r.,” https://web.archive.org/web/20120930192920/http://www.ipn.gov.pl/portal/pl/2/1002/Otwarcie_wystawy_8222Zbrodnie_w_majestacie_prawa_1944821119568221_8211_Krakow_2_.html.

- John R. Rarick, “The ‘Untouchable” Parade,” 114 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 114, Part 3 (February 8, 1968 to February 22, 1968), Extension of Remarks, February 5, 1968, in the House of Representatives, Thursday, February 8, 1968, 2860-2861, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1968-pt3/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1968-pt3-1-2.pdf.

- John R. Rarick, 115 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 115, Part 3 (February 5, 1969 to February 21, 1969), “Untouchables Undaunted” – Jacob Beam in the House of Representatives, February 5, 1969, 2970-2973, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1969-pt3/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1969-pt3-1-2.pdf.

- Ted Lipien, “Voice of America Russian Branch Chief Alexander Barmine Was An Ex-Soviet General and Ex-Spy Who Testified Before Senator McCarthy,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), April 17, 2023, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/voice-of-america-russian-branch-chief-alexander-barmine-was-an-ex-soviet-general-and-ex-spy-who-testified-before-senator-mccarthy/.

- Arch Puddington, Broadcasting Freedom: The Cold War Triumph of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2000) 125-126. Also see Yale Richmond, “Nixon in Warsaw,” American Diplomacy, November 2010, http://americandiplomacy.web.unc.edu/2010/11/nixon-in-warsaw/.