During World War II, Jan Ciechanowski, Polish Ambassador in Washington, helped expose Soviet propaganda and U.S. government propagandists, who, in domestic media and in “Voice of America” shortwave radio broadcasts for foreign audiences spread disinformation originating in Soviet Russia.

Photo: Jan Ciechanowski, Polish Minister, 11/30/25, LC-DIG-npcc-15231 (digital file from original), Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.

Americans concerned about Russian propaganda and Russian interference with U.S. elections are strangely not being told about similar and far more massive Soviet propaganda and disinformation campaigns in the United States during World War II, which were both openly and secretly assisted by Roosevelt administration officials in charge of American war information. In secret meetings, U.S. propagandists coordinated their news and information strategy with Soviet propagandists and wittingly or unwittingly tried to deceive Americans about the Soviet Union and Josef Stalin. They also misled foreign listeners to “Voice of America” radio broadcasts with a heavy dose of disinformation and propaganda on almost anything related to Russia.

Americans concerned about Russian propaganda and Russian interference with U.S. elections are strangely not being told about similar and far more massive Soviet propaganda and disinformation campaigns in the United States during World War II, which were both openly and secretly assisted by Roosevelt administration officials in charge of American war information. In secret meetings, U.S. propagandists coordinated their news and information strategy with Soviet propagandists and wittingly or unwittingly tried to deceive Americans about the Soviet Union and Josef Stalin. They also misled foreign listeners to “Voice of America” radio broadcasts with a heavy dose of disinformation and propaganda on almost anything related to Russia.

Americans also don’t know that one of the most relentless and formidable challengers of pro-Soviet U.S. government propaganda was a wartime Polish diplomat in Washington, Ambassador Jan Ciechanowski.

Ciechanowski started his diplomatic career in Poland’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1918 as the country regained its independence at the end of World War I. He served as secretary to Polish Prime Minister Ignacy Jan Paderewski, a statesman and a politician, a world-famous pianist and composer with strong ties to the United States, and a friend of President Woodrow Wilson. Ciechanowski attended the Paris Peace Conference with Paderewski. Later in the interwar period, he served at Polish embassies in Great Britain and the United States. He returned to Washington in 1941 as the ambassador of the Polish Government-in-Exile based in London. He remained in his post until 1945 when the Truman administration and most countries recognized the Soviet-dominated government in Warsaw. He could not return to Poland because of the threat of imprisonment by the communist regime and spent the rest of his life living in exile in the United States.

In a book published in 1947, Jan Ciechanowski described in some detail his mostly behind-the-scenes efforts in Washington to curb the pro-Soviet propaganda of some of the Roosevelt administration officials. As the Russian government of Vladimir Putin is again using some of the same disinformation tactics against the United States, Ambassador Ciechanowski’s warnings about Russian propaganda and the wartime collusion between American and Soviet propagandists have been, unfortunately, largely forgotten even though they could offer a valuable lesson on the dangers of allowing enemies of democracy to influence and corrupt national discourse and even the U.S. government itself.

Very few people today know about this remarkable Polish diplomat and his attempts to expose Soviet propaganda. Americans also don’t know about the still largely unpublicized efforts by many American government officials in the Roosevelt administration who were trying to cover up Stalin’s crimes. Among his many attempts to draw the attention of Americans to the true aggressive and cruel nature of the Stalinist regime, Ambassador Chiechanowski tried to get President Roosevelt to give political asylum to about 10,000 Polish children, many of them orphans, who had been prisoners along with their parents in the Soviet Gulag and had escaped from Russia in 1942. If successful, this could have shown the President, his administration, and the American people what Stalin was capable of doing, but Ciechanowski only succeeded in getting FDR’s approval to transport a small group of these refugee children on a U.S. ship and to resettle some of them in Mexico. Administration officials would not allow them to remain in the United States for Polish-American families to adopt them. U.S. authorities kept the Polish refugee children under military guard to prevent contact with the American public and media and to protect Stalin from any bad publicity.1

Very few Americans know that during World War II, the U.S. government’s overseas broadcasts, which later became known as “the Voice of America” and “VOA,” were under the control of pro-Soviet government bureaucrats and strongly Left-leaning broadcasters in the Office of War Information (OWI) which was created in 1942 to counter Japanese and Nazi propaganda, but not Soviet propaganda. Senior OWI officials secretly coordinated U.S. government propaganda, including the content of VOA broadcasts, with Soviet officials to match Stalin’s propaganda.

It is also worth noting that the Voice of America did not start broadcasting in Russian until 1947 because early OWI officials feared offending Stalin. Their enthusiasm for the Soviet dictator and Moscow-controlled communist movements was so pronounced in VOA radio broadcasts and other forms of wartime propaganda that it became intolerable at one point, even to President Roosevelt. He himself was more than willing to appease the Soviet Union on his own in order to keep Russia in the war with Hitler, and he also naively believed that Stalin could be persuaded to support peace and democracy in the post-war world. But Roosevelt drew the line when the lives of American soldiers were at immediate risk because of Voice of America commentaries reflecting the Kremlin’s point of view and supporting communist causes.

According to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the World War II Supreme Commander, communist-inspired excesses by early VOA broadcasters threatened the safety of U.S. troops when Voice of America programs ridiculed tactical agreements reached by him with some of the Vichy France and Italian leaders to lure them out of their former cooperation with Nazi Germany. President Eisenhower noted in his memoir published in 1965 that President Roosevelt put a stop to VOA’s “insubordination.”2 Of all the post-war U.S. presidents, Eisenhower was least enthusiastic about the Voice of America and was involved in creating more hard-hitting Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty.

Even after President Roosevelt’s brief intervention and the forced resignation in 1943 of John Houseman, who was later described as the first Voice of America director, pro-Soviet and pro-communist propaganda in wartime VOA broadcasts continued for the rest of the war regarding Poland and other countries in East Central Europe. President Roosevelt had secretly agreed that they should fall under Russia’s influence in response to Stalin’s aggressive demands at their wartime summit conferences in Tehran and Yalta.

Jan Ciechanowski, who from 1941 until July 5, 1945, served in Washington as the Ambassador of the Polish Government-in-Exile based in London, wrote in his 1947 book Defeat in Victory about his struggles with pro-Soviet propagandists in the Roosevelt administration. During the war, Ciechanowski tried to warn administration officials, members of Congress, and journalists about Soviet influence within the Office of War Information, including the Voice of America radio broadcasting section. He and other critics of the Office of War Information persuaded enough Congress members to limit drastically OWI’s funding for domestic propaganda in the United States. In 1943, the House Appropriations Committee slashed the Roosevelt administration’s request for the Domestic Branch of the Office of War Information’s budget by nearly 40 percent to $5.5 million (approximately $97 million in 2023) after President Roosevelt indicated that he would not battle with Congress on behalf of the agency. The whole House voted 218 to 114 to abolish the OWI’s Domestic Branch entirely, with most Republicans and Southern Democrats wanting to end government-funded domestic propaganda activities. The Senate voted to preserve approximately $3.6 million, and the conference committee left the Domestic Branch with only $2,750,000 (approximately $48 million in 2023).3 Progressive and pro-labor northern Democrats who represented large ethnic communities with origins in Eastern Europe and had heard from their constituents and Ambassador Ciechanowski about OWI’s pro-Soviet activities also voted to end domestic government-funded political propaganda. OWI’s larger budget for overseas broadcasts was saved only by a few votes. Republicans in Congress were particularly upset by what they saw as OWI’s and VOA’s partisan electoral messages designed to benefit President Roosevelt. Even the State Department secretly intervened with the White House to get some of the most pro-Soviet Voice of America officials and broadcasters removed, including VOA Director John Houseman, who later became a successful Hollywood actor.

Ambassador Ciechanowski’s efforts were, however, ultimately unsuccessful in changing President Roosevelt’s overall policy of appeasing Stalin. Only several years after the war, his warnings about Russian propaganda were publicized in bipartisan hearings conducted by the U.S. House of Representatives, which prompted programming reforms at the Voice of America. Along with Radio Free Europe, VOA played a significant role later in the Cold War in helping to undermine the communist monopoly on news and contributed to the eventual peaceful collapse of the Soviet empire.

Jan Ciechanowski, Polish Minister, 11/30/25, LC-DIG-npcc-15231 (digital file from original), Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.

Jan Maria Włodzimierz Ciechanowski (1897-1973)

Defeat in Victory (Doubleday, 1947)

“Of all the United States Government agencies, the Office of War Information [where Voice of America radio broadcasts in English and many other languages originated], under its new director, Mr. Elmer Davis, had very definitely adopted a line of unqualified praise of Soviet Russia and appeared to support its shrewd and increasingly aggressive propaganda in the United States. The OWI broadcasts to European countries had become characteristic of this trend.”4

“But, curiously enough, while some [U.S.] government departments realized the danger of unduly encouraging Soviet-Russian appetite, some of the new war agencies actively conducted what could only be termed pro-Soviet propaganda.”5

“So-called American propaganda broadcasts [Voice of America, originally called “America Calling Europe”] to occupied Poland were outstanding proofs of this tendency. Notorious pro-Soviet propagandists and obscure foreign communists and fellow travelers were entrusted with these broadcasts.”6

“I protested repeatedly against the pro-Soviet character of such propaganda. I explained to those responsible for it in the OWI that the Polish nation, suffering untold oppression from Hitler’s hordes, was thirsting for plain news about America and especially about her war effort, her postwar plans, and her moral leadership, that Soviet propaganda was being continuously broadcast anyway to Poland directly from Moscow, and there seemed no reason additionally to broadcast it from the United States.”7

“When I finally appealed to the Secretary of State and to divisional heads of the State Department, protesting against the character of the OWI broadcasts to Poland, I was told that the State Department was aware of these facts but could not control this agency, which boasted that it received its directives straight from the White House.” 8

“I was painfully conscious at the time,” former World War II Polish Government-in-Exile Ambassador to Washington Jan Ciechanowski wrote in October 1952, “that the sole aim of winning the war militarily and the consequent anxiety to avoid any gesture that might irritate that most valuable ally – the Soviets, dominated American policy so completely that all other political and even human considerations were subordinated to the one major objective of preserving Soviet friendship.”9

One of the human considerations in international politics during much of World War II was the mystery over the fate of thousands of Polish prisoners of war in Soviet captivity and the uncertain fate of hundreds of thousands of Polish deportees languishing in prisons, labor camps, and in forced exile in the Soviet Union. In 1939, the Red Army took as prisoners of war officers and soldiers of the Polish Army and Border Defense Corps, officers of the state police, and functionaries of other Polish state services. From 1939 to April 1940, they were kept in special prison camps of the Soviet NKVD secret security service in Kozelsk, Starobelsk, and Ostashkov. The NKVD also arrested thousands of Polish civilians for being “intelligence agents and gendarmes, spies and saboteurs, former landowners, factory owners and officials.” They were placed in prisons on the eastern territories of the Republic of Poland occupied by the USSR in 1939. The Soviet occupation of eastern Poland followed the secret protocol of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, also known as the Nazi-Soviet or the Hitler-Stalin Pact. Under this treaty, signed in Moscow on August 23, 1939, Hitler attacked Poland on September 1; Stalin on September 17, violating the 1932 Soviet–Polish Non-Aggression Pact and starting the Second World War.

Some 250,000 Polish officers and soldiers were taken into captivity during the Soviet occupation of eastern Poland in 1939. Of these, the Soviets executed over 21,800 Polish citizens in a mass murder carried out at various locations between March and an unspecified date in 1940. Stalin and other members of the Soviet Politburo signed their death warrant on 5 March 1940, condemning Polish 21,857 prisoners to “the supreme penalty: shooting” for being “hardened and uncompromising enemies of Soviet authority.” The NKVD murdered about 4,400 prisoners from the camp in Kozelsk in the Katyn forest near Smolensk in Russia. Other executions happened elsewhere. The Katyn massacre usually refers to all executions of Polish citizens under the 1940 Soviet Politburo secret decree, but only some of the victims were killed and buried in Katyn.

Those murdered were Poland’s military, political, and intellectual leaders. Katyn’s victims included 20 university professors, 300 physicians, several hundred lawyers, engineers, teachers, and more than 100 writers and journalists. They were among 3,420 non-commissioned officers found dead in the Katyń graves. Among the dead were also one admiral, two generals, 24 colonels, 79 lieutenant colonels, 258 majors, 654 captains, 17 naval captains, about 200 pilots, seven chaplains, three landowners, a prince, 43 officials, 85 privates, and 131 refugees.10

The Soviets did not announce this and other executions, which the NKVD carried out in complete secrecy. Joseph Stalin and other Soviet leaders later refused to provide definite information about the fate of these missing prisoners of war to Polish, American, and British officials seeking answers. When the German soldiers discovered the mass graves in Katyn in the spring of 1943, the Soviets falsely blamed the crime on the Nazis. When the Polish Government-in-Exile requested an impartial investigation by the International Red Cross, Stalin used it as a pretext to break diplomatic relations, thus opening the way for installing in Poland after the war a communist government dominated by Moscow.

According to estimates by the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN), roughly 320,000 Polish citizens were deported to the Soviet Union, of which nearly half, 150,000, died under the Soviet rule during World War II as a result of starvation, disease, hard labor, harsh weather, degrading treatment, torture, and executions. Other historians believe the total numbers of deportees and those who had perished in Russia were even higher. After Hitler launched his surprise attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Polish Government-in-Exile in London reached out to Moscow. The two sides signed an agreement in which the Kremlin promised to release all Polish prisoners in the Soviet Union. A Polish army was to be formed in Russia under the command of Polish general Władysław Anders, newly released from a Soviet prison. To his surprise and great concern, he could not find thousands of Polish officers nor get any reasonable explanation for their possible whereabouts from Soviet leaders. Eventually, the Polish government got Stalin’s approval to move General Anders’ army from Russia to Iran. It later fought on the side of the allies in North Africa and Italy. Thousands of Polish civilian refugees were also evacuated from Russia, including many orphans whose parents were killed or died in Soviet captivity.

In his memoirs, Ambassador Ciechanowski describes his conversation with U.S. Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles after Stalin broke diplomatic relations with the Polish Government-in-Exile on April 26, 1943. Stalin objected to Poland’s request to the International Red Cross for an independent investigation of the Katyn massacre.

“On my part, I drew Mr. Welles’s special attention to the necessity of curbing the exaggerated pro-Soviet tendency of OWI propaganda at this delicate moment.”11

“He promised he would try to do so.”12

“Thus, in the case of Katyń,” Ambassador Ciechanowski noted in his 1952 letter to a congressional staffer, “the unprecedented horror of the cold-blooded murder of thousands of allied officers and men, the fact that their murder had deprived the Polish army, then being formed in Russia of a most valuable cadre of officers, the fact that this dastardly act might seriously affect the fighting spirit of the Polish Armed Forces and of the Polish Nation were all brushed aside by the United States Government in its anxiety to hush up the so-called ‘Katyń incident,’ lest it affect the all-important good relations between Washington and the Kremlin.”13 In his 1948 book Defeat in Victory, Ambassador Ciechanowski wrote: “Some of the new war agencies actively conducted what could only be termed pro-Soviet propaganda.” “So-called American propaganda broadcasts to occupied Poland were outstanding proofs of this tendency. Notorious pro-Soviet propagandists and obscure foreign communists and fellow travelers were entrusted with these broadcasts,” he added. He was right.

This thoughtful, old-school Polish diplomat was well aware of official American eagerness to appease the Soviets during World War II and to promote Soviet propaganda while restricting and censoring news that might have presented Soviet Russia in a deservedly negative light to Americans and foreign audiences. These historical facts remain unknown to most Americans because they were also suppressed by U.S. Executive Branch officials who replaced those who had worked for American propaganda during World War II. But not all Americans participated in the official cover-up. Members of the U.S. Congress of both parties were most emphatic in establishing the truth about Katyń and exposing other Soviet crimes. While serving in Washington as the ambassador of democratic Poland, Jan Ciechanowski reached out to many of them and found positive reception as he waged fierce behind-the-scenes battles with the wartime Office of War Information and the Voice of America.

“Contrary to OWI and fellow-traveler propaganda, American public opinion was becoming apprehensive that the Soviets were not turning out to be an ideal of ‘radical democracy’ and beginning to wonder if it was not more judicious to seek reinsurance in world affairs in a more natural association between the two English-speaking democracies.”14

“In the atmosphere of silence inspired by the OWI on all Soviet-Polish matters, the publication of excerpts from the Polish and Soviet declarations suddenly revealed to public opinion the existence of an acute Soviet-Polish problem.”15

“This revelation coincided with the rising anxiety that, contrary to officially inspired enthusiasm, the Teheran meeting had not been the unqualified success it was made out to be. I frequently heard expressions of criticism of the President for his ‘secret diplomacy,’ and suspicious that, behind the curtain drawn around Teheran, secret agreements had been concluded. The approach of the election campaign was making public opinion noticeably more alert and critical.” 16

Ambassador Ciechanowski’s account of his 1944 conversation with Louis Fischer, an American writer and expert on Soviet affairs.

“In his opinion, the President and American official circles had become so personally engaged in pro-Soviet propaganda that it was difficult to imagine how they could ‘go into reverse’ at this time, when internal political considerations were playing such a big part.”17

In his posthumously published memoirs, Loy W. Henderson, a U.S. diplomat who was one of the prominent early experts on Soviet Russia and later served as ambassador to Iran and India and occupied senior positions in the State Department, devoted a long and highly favorable section to his dealings with Ambassador Ciechanowski and his book Defeat in Victory.

His book has been read by relatively few Americans. Professors in our universities rarely place it on the prescribed reading lists of their students. In general, we Americans prefer to forget what happened to Poland, the country for the independence of which Great Britain and France allegedly went to war with Germany to defend. The book does not make pleasant reading for those who believe in the rights of peoples, which President Roosevelt and Churchill eloquently proclaimed during the early years of the war, or who subscribe to the principles set forth in the charter of the United Nations. My main criticism of the book is the tendency of the author to place too much of the blame on the members of the Department of State for the decisions that contributed to the failure of Poland to regain independence. The members of the department of whom he was critical were not responsible for these decisions. They merely had the unpleasant duty of putting them into effect.18

Count Jerzy Potocki was the Polish Ambassador in Washington when Henderson served in the East European area of the Department of State in 1938. Henderson wrote in his memoirs that following the invasion of eastern Poland by Soviet armed forces in the middle of September 1939 under the secret terms of the Hitler-Stalin Pact, left-wing groups in the United States began to argue that Poland was a fascist country and claimed that the Soviets were liberating workers and peasants from the Polish exploiters. Henderson noted that because of his background and aristocratic landowner family, which made Potocki a vulnerable target for this type of pro-Soviet propaganda, the Polish Government-in-Exile in London replaced in 1941 Potocki with Ciechanowski, who had a reputation of being more to the left of the political spectrum in Poland and thus more “acceptable to the more moderate New Dealers.”19. Henderson expressed his deep personal disappointment that despite Ambassador Ciechanowski’s tenacious and courageous struggle, Poland lost its independence because “most of the New Dealers who had influence in the White House, as well as President Roosevelt, were prone to yield to the insistence of the Soviet Union.”20

For additional information, see one of the earlier Cold War Radio Museum articles updated and reposted below.

Polish Ambassador’s Fight With Pro-Stalin Voice of America and Soviet Propaganda in the U.S.

By Ted Lipien

Polish envoy Jan Ciechanowski with family in front of the Polish Embassy in Washington in 1925. LC-DIG-npcc-15230 (digital file from original), Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 2054

Anybody looking for evidence of widespread and effective Russian interference in American politics and considerable influence within the U.S. government must look no further than the World War II era Voice of America (VOA). The U.S. wartime mega propaganda agency, the Office of War Information (OWI), included since 1942 a radio broadcasting division that only later became known as the Voice of America. From the beginning, the OWI and its Voice of America radio broadcasts generated plenty of controversy in Washington, much of which is now forgotten and omitted from many historical accounts. However, during the war and into the early 1950s, pro-Soviet propaganda and Soviet influence among VOA staffers was the subject of many congressional speeches and newspaper articles, most of them highly critical of the Voice of America and its federal parent agency.

Voice of America reporting during the war was, in fact, closely coordinated with Soviet propaganda by one of VOA’s founders, Hollywood playwright and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s speechwriter Robert E. Sherwood. The coordination was conducted, for the most part, with full approval from FDR. It was no secret that VOA engaged in pro-Soviet propaganda, which one critic, a former VOA journalist Julius Epstein, later described as “Love for Stalin.”

Officials and VOA writers deceived international public opinion and, at that time, also many Americans, since their programs were distributed in the United States, by covering up Stalinist crimes and Moscow’s true intentions with regard to Eastern and Central Europe. At one point during the war, even the AFL and CIO, a U.S. labor federation that could hardly be called reactionary, severed its cooperation with the Voice of America and accused its leadership of being dominated by communists and communist sympathizers.

Perhaps only a few of OWI’s employees were members of the Communist Party. Still, many of them, and especially their bosses, pushed the Soviet line, often to the detriment of U.S. interests. By 1942, both Poland, represented by the Polish Government in Exile based in London, and the Soviet Union, were America’s allies in the war against Nazi Germany. By that time, the Soviets, who earlier in the spring of 1940 had secretly murdered over 20,000 Polish military officers, Polish government leaders, and intellectuals, were already hard at work trying to discredit the democratic Polish government, as well as democratic governments in exile of other Nazi-occupied European nations, including Greece and Yugoslavia. Stalin broke diplomatic relations with the Polish government when the Germans discovered the mass graves of murdered Polish officers in the spring of 1943 in Katyn near Smolensk in western Russia. The Voice of America, under its strongly pro-Soviet director, Hollywood actor John Houseman, immediately adopted and promoted the Soviet lie that the Germans were responsible for the murders. Even the U.S. State Department urged VOA to be cautious in accepting the Soviet version, but those in charge of VOA ignored the warning. At the same time, VOA’s parent agency, the Office of War Information, intensified its illegal efforts to censor American media outlets, mostly of Polish-American and other ethnic origin, which were reporting that Stalin had ordered the mass murder of Polish prisoners of war and was planning to turn Poland into a Soviet satellite state. They were right on both accounts, but the OWI censors viewed their honest reporting as detrimental to the war effort.

The Polish Ambassador to Washington, Jan Ciechanowski, who represented the Polish Government-in-Exile during the war, was responsible for exposing the Soviet influence within the Office of War Information and the Voice of America to members of Congress and mainstream American media. As a traditional diplomat, he worked mainly behind the scenes, and his activities in fighting Soviet propaganda never became well known, even after the war. But thanks to his efforts, the Office of War Information nearly lost all of its funding from Congress in 1943 over management scandals and domestic media censorship that he helped to expose. Eventually, only part of the OWI budget was cut for its domestic propaganda service, but Congress sent a strong message of displeasure with the agency over the pro-Soviet activities of its officials.

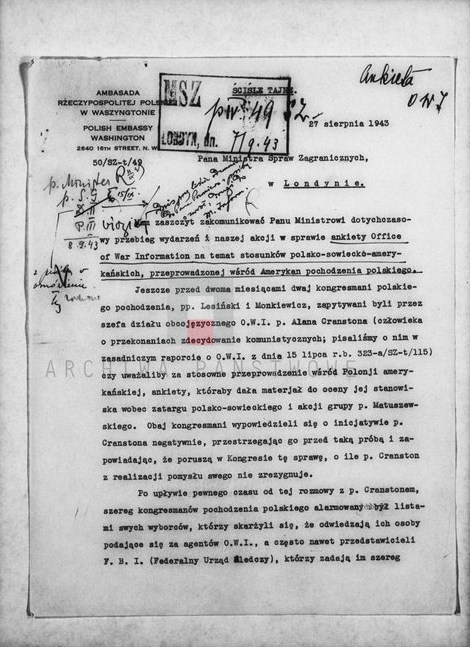

Ambassador Ciechanowski’s then-secret diplomatic cables to his government in London, which are now archived at the Hoover Institution, describe in detail the extent of pro-Soviet WWII Voice of America propaganda (VOA was not yet then widely known by its current name; the diplomatic cables refer to OWI’s overseas and domestic media activities) and the staffing of the OWI Polish desk by pro-Soviet activists and writers. The cables also reveal Ciechanowski’s protests to the State Department and his lobbying among members of Congress to stop OWI’s pro-Stalin propaganda and illegal censorship of U.S. media.

This is the first time information from Ambassador Ciechanowski’s secret diplomatic cables about the pro-Soviet activities of the U.S. propaganda agency during World War II is being reported in significant detail in English. Jan Ciechanowski (1887-1973) was an economist and a distinguished Polish diplomat in London and in the United States before the war. He served in Washington during the war. One of his last diplomatic acts before the United States Government withdrew its recognition from the democratic Polish government in London and recognized the Communist-dominated government in Poland was to point out to State Department officials that their initial decision to make the formal announcement on the 4th of July 1945 was less than appropriate to make on America’s Independence Day. The United States made the announcement on July 5th.

In 1947, Jan Ciechanowski published his diplomatic memoirs, Defeat in Victory. The book includes descriptions of his battle with the Office of War Information and its Voice of America officials and staffers to counter Soviet propaganda and censorship. After the war, he continued to live in exile in the United States until his death in 1973.

In 1947, Jan Ciechanowski published his diplomatic memoirs, Defeat in Victory. The book includes descriptions of his battle with the Office of War Information and its Voice of America officials and staffers to counter Soviet propaganda and censorship. After the war, he continued to live in exile in the United States until his death in 1973.

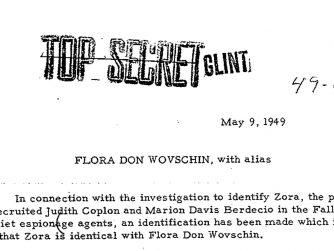

Ambassador Ciechanowski’s actions, described much more frankly and in much greater detail in his WWII cables, had only a temporary and minimal effect on VOA’s pro-Soviet propaganda at the time. Still they prompted Congress in 1943 to cut the OWI’s budget for domestic propaganda activities, which included censorship of U.S. domestic media. After the war, the bipartisan Madden Committee (named after Democratic lawmaker from Indiana Ray Madden and charged with investigating the Katyn massacre) condemned these U.S. government media censorship activities as illegal. (OWI was also responsible for producing films in support of the internment of U.S. citizens of Japanese ancestry.) OWI’s key functionary responsible for domestic U.S. media censorship, including the silencing of Polish American radio programs in Detroit and Buffalo, which broadcast the truth about Katyn, was the future U.S. Senator from California Alan Cranston. In a secret diplomatic cable, Ambassador Chiechanowski described Cranston as a man of definite pro-communist convictions.

As a result of Ambassador Ciechanowski’s relentless behind-the-scenes actions, members of Congress and U.S. media started to ask questions about OWI activities and VOA programs. The management, staffing, and activities of these propaganda organizations became very controversial and eventually led to the abolishment by President Truman of the Office of War Information in 1945. He placed the much reduced Voice of America under the State Department. Congress passed, and President Truman signed the Smith-Mundt Act of 1948, which imposed restrictions on the U.S. government’s domestic propaganda and established strict hiring procedures and security checks to avoid employing foreign agents.

Contrary to the legend of the U.S. government-funded and run Voice of America as the purveyor of nothing but the truth, no matter how bad the news was for the United States, WWII VOA was a powerful propaganda tool of the White House, but primarily for its own officials and staffers. VOA broadcast Soviet disinformation and covered up Stalin’s crimes, not just the brutal killing of over 22,000 Polish officers, other POWs, and political and intellectual leaders, but also executions and deportations of hundreds of thousands of Polish civilians from the Polish territory occupied by the Soviet Union in 1939 in accordance with the Secret Protocol of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. OWI and VOA deceived Americans and foreign audiences about Polish refugees fleeing Russia, including many children who had lost their parents in the Soviet Gulag. While other European countries, including Greece and Yugoslavia, were also targets of pro-Soviet VOA propaganda, Ambassador Ciechanowski’s focus was understandably on Poland. Still, he also cooperated with diplomats of these countries in Washington in exposing Soviet influence within the Voice of America.

Ambassador Ciechanowski was right to issue his warnings. After the war, the head of wartime VOA Czechoslovak Service, Dr. Adolf Hofmeister, returned to Czechoslovakia and joined the communist government as its ambassador to Paris. The wartime VOA Polish Service also had its famous defector to the communist side, Stefan Arski. Former OWI editor Julius Epstein wrote after the war about Soviet sympathizers in the German Service and among the top leadership of the Voice of America.

In his July 13, 1943 cable to Edward Raczyński, Foreign Minister of the Polish Government-in-Exile in London, Ambassador Ciechanowski wrote:

“I would like to inform the Minister of an action I am undertaking to call attention of the American public opinion, Congressional circles and some American government circles which have an objective view of Soviet affairs, to the biased attitude of the [U.S.] government propaganda bureau, the Office of War Information (OWI), toward Polish-Soviet issues.”

“Initially, when American propaganda offices were headed by Colonel Donovan (Coordinator of Information) and Archibald MacLeish (Office of Facts and Figures), the Embassy had very close relations with these two offices, and their friendly view of Poland’s cause could not be questioned,” Ambassador Ciechanowski reported to his government.

“The situation worsened from the moment when the C.O.I. and O.F.F. offices were combined under the leadership of Elmer Davis, a journalist little familiar with European issues, crude, completely committed to the idea of using commercial advertising methods—in the American style—in political propaganda,” Ciechanowski’s cable continued.

According to Ciechanowski, Elmer Davis’ shortcomings and advertising methods scared away from OWI some of the best American journalists to be replaced by mediocre reporters “completely subservient to Davis’ politicized assistants.” Ciechanowski described Davis’ closest assistants as “pronounced sympathizers of Russia and communism.” He listed Robert E. Sherwood, James Cowles, James P. Warburg, and Joseph Barnes.

“Polish affairs were placed in the hands of a group of Polish citizens manifesting their pro-Soviet stand,” Ciechanowski wrote. He said that he had personally protested to Elmer Davis but that his protest had no effect. He also reported that Ambassadors from Greece, Holland, and Yugoslavia made similar protests about communist influence at the OWI, reflected in Voice of America broadcasts abroad, also to no avail.

Ciechanowski pointed out later in the July 13, 1943 cable that, as a result of his complaints, Elmer Davis hired Dr. Ludwik Krzyżanowski, a Pole friendly to the Polish Government in Exile, to work at the OWI headquarters in Washington (Voice of America programs to Poland were mostly done by the pro-Soviet team in New York). Ambassador Ciechanowski noted, however, that Dr. Krzyżanowski may not have had enough influence to stop pro-Soviet propaganda.

Dr. Krzyżanowski indeed could not make much of a difference in the bureaucratic government agency committed by its senior leadership and through the work of many of its staffers to promote appeasement of Joseph Stalin, which was, in any case, the official U.S. policy set by President Roosevelt and his closest advisors, including Elmer Davis. Dr. Ludwik Krzyżanowski (1906-1986), who had come to the United States in 1938 to be a cultural attache of the Government of Poland, was later a professor in the Department of Slavic Studies in Columbia University and Editor-in-Chief of The Polish Review—a scholarly quarterly of the Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences of America.

As relations between the Polish Government-in-Exile and Russia worsened over the Katyn massacre, “the OWI’s attitude toward us started to worsen more and more,” the Polish Ambassador reported.

He wrote that OWI officials refused help with arranging a special U.S. nationwide broadcast to commemorate the May 3rd Polish Constitution Day in 1943, even though the Embassy arranged for Congressional leaders of both parties to speak. These observances came a few weeks after the Germans announced the discovery of the Katyn graves of thousands of executed Polish officers, and the OWI and VOA started to push the Soviet propaganda line that the Nazis had committed the murders. Acting independently, however, the Embassy managed to get the Columbia Broadcasting System to give airtime for the special program on all stations on its network. Ambassador Ciechanowski then explained how the OWI censored, in overseas Voice of America broadcasts, the Polish Government’s statements about the Katyn Massacre while airing Soviet statements.

“…our relations with the press were not damaged by OWI’s hostile attitude. On the contrary — adjusting efforts by directly contacting the media while avoiding the O.W.I. produced better results than going through an intermediary. But in spite of this, the OWI made our life difficult, especially during the period of the “Katyn Affair,” by withholding through censorship all of our major statements while letting the Soviet ones go through.”

President Roosevelt was convinced that pro-Soviet propaganda activities and censorship of Stalin’s political and war crimes were necessary to keep Russia as America’s ally against Germany and later Japan. The Office of War Information was a huge federal bureaucracy accountable to no one except its director, Elmer Davis, and through him to President Roosevelt. But VOA became so unabashedly pro-Soviet that it eventually drew the wrath of many members of Congress, the U.S. press, and even the State Department, and, in one case, the White House.

In 1943, OWI officials planned and partially conducted what was presented as a public opinion survey among Polish Americans, which included leading pro-Soviet questions. Some of them implied that Poland, which was then a military ally of the United States with her troops fighting alongside the Western allies, should consider agreeing to Stalin’s territorial demands. Other questions seemed to cast doubts on the legitimacy of the Polish Government-in-Exile in London, with which Washington still maintained full diplomatic relations. At that time, Ambassador Ciechanowski continued to meet regularly with State Department officials, including Secretary of State Cordell Hull, and had meetings with President Roosevelt, as did the visiting Polish Government-in-Exile prime ministers, Władysław Sikorski and later Stanisław Mikołajczyk, until Washington broke relations with the London-based Polish Government in July 1945. U.S. media commentators critical of OWI’s activities declared the poll to be intentionally biased in favor of Russia.

In a column published on August 20, 1943 in the WashingtonTimes-Herald, newspaperman John O’Donnell wrote:

“The misnamed Office of War Information has apparently decided to end its career by suicide and this may be all for the best.

Few honest newspaper tears are going to be shed over the demise of an outfit which from birth was a New Deal Roosevelt propaganda body (as discovered by the last Congress which amputated its domestic claws) and throughout its career gave off the distinctly unpleasant stench of being a parking place for pay-roll patriots, political stumble bums and the incompetent sweepings of editorial rooms.”

(…)

“Freedom might well shriek if some of the descendants of that original liberty Pole [General Tadeusz Kosciuszko] were faced with these latest OWI questions to Americans with Polish names. … the questions are framed with a strictly pro-Russian slant, in our opinion.”21

As a result of public criticism and pressure, including a protest from the U.S. State Department and members of Congress, the OWI was forced to stop its polling of Polish Americans. But Elmer Davis and VOA broadcasters continued to ignore advice from high-level State Department officials, including Assistant Secretary of State Adolf A. Berle, who warned them not to place the blame of the Katyn massacre on the Germans and to avoid the entire controversy as much as possible. President Roosevelt’s friend and foreign policy advisor, Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, secretly warned the White House that the Office of War Information, including its Voice of America division, was heavily under the influence of a foreign power.

Even before the Office of War Information launched the controversial poll in 1943 among Polish Americans, the U.S. Congress drastically reduced the OWI domestic division’s budget as criticism of the mega propaganda agency grew nationwide, and legislators expressed their strong disapproval of the agency’s foreign and domestic activities. Detailed information about the OWI poll was given to the U.S. press and members of Congress by Ambassador Ciechanowski and Polish diplomats in Washington and other major U.S. cities.

Overseas audiences were not the only ones being misled by the U.S. Government with pro-Soviet propaganda. During World War II, the Office of War Information engaged in censoring private commercial Polish American broadcasters who were accurately accusing Stalin of ordering the 1940 massacre of thousands of Polish officers and other POWs at the Katyn Forest near Smolensk and other locations in the Soviet Union.

Sometime in April 1943, OWI director Elmer Davis wrote a special radio commentary in which he blamed the Katyn Massacre on the Nazis. At the time, he State Department advised the OWI to avoid reporting on the Katyn story altogether “if at all possible” because the evidence was inconclusive.

This kind of news censorship would have also been bad, but Elmer Davis and the Voice of America made it even worse and gave full support to the Soviet lie. Davis later claimed he was convinced the Germans were responsible for the murders. He, however, almost certainly had access to information that the evidence pointed strongly to the Soviet responsibility for the crime. As a journalist, he could have easily asked questions of the right sources, including State Department officials, Ambassador Ciechanowski, and some American reporters who covered the Soviet Union from Washington, New York, or Chicago. “Mr. Davis, therefore, bears the responsibility for accepting the Soviet propaganda version of the Katyn massacre without full investigation,” the bipartisan Select Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives, which investigated the Katyn Massacre, concluded in its final report in 1952,

Not satisfied with censoring VOA news, another OWI official, Alan Cranston, who later became a U.S. Senator from California, used illegal tactics to pressure commercial U.S. broadcasters to drop Polish American radio programs in which the truth about Katyn was being told. After the war, the Select Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives also investigated these activities and declared them illegal.

But even during the war, OWI’s pro-Soviet bias, its handling of the Katyn story in overseas Voice of America broadcasts, Elmer Davis’s commentary, the censorship of Polish American radio stations, and finally, OWI’s public opinion poll became known, largely through the efforts of the Polish Embassy. They outraged the Polish American community and their representatives in Congress.

Speaking on the floor of the House in 1943, members of Congress revealed that some OWI managers lacked any experience in foreign affairs and some OWI journalists were open Soviet sympathizers if not actual members of the Communist Party. A few WWII Voice of America broadcasters and contributors later joined Communist governments in Eastern Europe. Only two or three were later identified through the Venona counter-intelligence program initiated by the United States Army Signal Intelligence Service (a forerunner of the National Security Agency) as actual Soviet agents or Soviet agents of influence.

Voice of America Polish desk commentator Artur Salman, who wrote under the pen name Stefan Arski, left VOA and the United States after the war and returned to Poland. He became the chief anti-American propagandist in Warsaw, writing articles virulently attacking the U.S. Congress for its investigation of the Katyn Massacre. Voice of America’s censorship of the Katyn story in one form or another continued into the late 1970s. That was not true with the U.S.-funded surrogate broadcasters Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty. They were able to broadcast the whole truth about Katyn in newscasts, interviews and historical programs. They were created after the OWI was broken up, and the Voice of America, then under the State Department, proved to be initially ineffective in responding to Soviet propaganda.

Jan Ciechanowski with his wife and children. No date. LC-DIG-ggbain-38809 (digital file from original negative), Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540, USA.

1943

Copy of the first page of Ambassador Jan Ciechanowski’s cable from the Polish Embassy in Washington to the Polish Government in Exile in London, dated August 27, 1943.SECRET

POLISH EMBASSY

WASHINGTON

July 13, 1943

To Minister of Foreign Affairs in London

I would like to inform the Minister of an action I am undertaking to call attention of the American public opinion, Congressional circles and some American government circles which have an objective view of Soviet affairs, to the biased attitude of the government propaganda bureau, the Office of War Information (OWI), toward Polish-Soviet issues.

This above topic has already some history behind it. Initially, when American propaganda offices were headed by Colonel Donovan (Coordinator of Information) and Archibald MacLeish (Office of Facts and Figures), the Embassy had very close relations with these two offices and their friendly view of Poland’s cause could not be questioned. Polish affairs were in the hands of such Americans as: Edgar A. Mowrer, Betty Carter, A. Oldes, Lee House and several others. With their help, the Embassy was able to organize several propaganda campaigns of first-rate significance of which the Minister is aware, such as: the 3rd of May [Poland’s Constitution Day] observances last year throughout the entire United States, publication of the booklet “Tale of a City,” excellent press coverage of the visits by Prime Minister General Sikorski, etc. The Embassy also relied on the friendly attitude of the leadership and officials of the propaganda offices in its daily, very frequent interventions, suggestions, and delivery of materials to the press and radio commentators, etc.

The situation worsened from the moment when the C.O.I. and O.F.F. offices were combined under the leadership of Elmer Davis, a journalist little familiar with European issues, crude, completely committed to the idea of using commercial advertising methods — in the American style — in political propaganda. Davis, aware of his ignorance, left political affairs in the hands of its assistants, such individuals as: Robert E. Sherwood, James Cowles, James P. Warburg, Joseph Barnes — all, without exception, pronounced sympathizers of Russia and communism, and — in the case of Cowles and Barnes — Willkie’s traveling companions on his trip to Russia and top promoters of the policy of “appeasement” toward Stalin.

Davis’ ignorance and advertising methods scared away from O.W.I. many of some of the most serious journalists who had been recruited before by Colonel Donovan and MacLeish, for example Henry F. Pringle, a well-known writer for the “Saturday Evening Post”; Ph. Hamburger, a commentator for the famous “New Yorker” and the author of our booklet “Tale of a City; Edgar A. Mowrer, I. Visson, and fifteen others who had left the O.W.I. under some scandal. The chief of the O.W.I. press section, outstanding former editor of the “San Francisco Chronicle,” Paul Clifford Smith, our sincere friend, also resigned.

The O.W.I. started to attract mediocre journalists completely subservient to Davis’ politicized assistants mentioned above. Polish affairs were placed in the hands of a group of Polish citizens manifesting their pro-Soviet stand, such as T.N. Hudes, Al. Hertz, Art. Salman, M. Zlotowska and politically disoriented because of her long-term absence from Poland Mrs. Irena Balinska. She reports to Joseph Barnes, a declared communist, preparing flyers and propaganda publications designed for distribution in Poland.

As soon as this situation developed, I personally called Mr. Davis’ attention during a special visit to the inappropriate selection of Polish personnel. Despite his promises, my intervention produced no results. Similar interventions by Ambassadors from Greece, Holland and Yugoslavia– countries whose O.W.I. desks are staffed by communists and army and navy deserters, etc.–also met the same fate.

As our relations with Russia worsened, O.W.I. attitude toward us started to worsen more and more. For example, we were refused help in organizing this year’s 3rd of May radio program to be broadcast in the United States nationwide despite willingness by Congressional Majority and Minority leaders, McCormack and Martin, to record speeches. This, however, did not prevent us from moving forward with the program. Thanks to our personal contacts, the Columbia Broadcasting System gave us airtime needed on all stations on its network within two days. As the Minister knows from my report on the 3rd of May observances (No. 337a/SZ-114 from June 10, [19]43) the program was excellent. Similarly, our relations with the press were not damaged by O.W.I.’s hostile attitude. On the contrary — adjusting efforts by directly contacting the media while avoiding the O.W.I. produced better results than going through an intermediary. But in spite of this, the O.W.I. made our life difficult, especially during the period of the “Katyn Affair,” by withholding through censorship all of our major statements while letting the Soviet ones go through.

I have been exerting pressure on the O.W.I and will continue to exert it through several avenues. First of all, I inform the State Department about each confirmed O.W.I.’s biased report. However, the State Department is powerless. Secondly, I maintain very friendly relations with Mr. George Creel, currently the editor of the “Collier’s” weekly, the chief of American propaganda during the previous war and President Wilson’s close associate. Thanks to his position and his previous activity, Creel who is a very courageous man and, unlike Davis, very informed, in his direct talks with Davis points out mistakes and is not shy with sharp criticism. Additionally, Creel has access to leading members of the Senate, such senators as Bridges, Tydings, Byrd, and presents them with all of our complaints against the O.W.I. without revealing their source.

Thirdly, and finally — I am conducting my action through members of Congress who are of Polish descent. The Minister can be informed in detail by reading the attached “Congressional Record” (from June 17, 1943).

Our intensified pressure on the O.W.I., especially in regard to the disastrous selection of the Polish staff, convinced Elmer Davis to look for a Polish citizen whose views are close to our official propaganda in the United States. The person selected was Dr. Ludwik Krzyzanowski, a former P.I.C. employee, editor of “New Europe.” Presently, Dr. Krzyzanowski works in Washington at the O.W.I. headquarters and maintains a close contact with us. In his view, the attack on the O.W.I. in Congress, led in large part by us and by Creel and which resulted in a significant cut in the institution’s budget, sobered some O.W.I. elements and convinced them to slow down the tempo of official pro-Soviet American propaganda. He does not believe, however, that this will last long. The O.W.I.’s staffing is too one-sided to expect changes in its political stand without major removals which are unlikely at the present time.

Our cooperation with Dr. Krzyzanowski is developing satisfactorily, but it remains to be seen whether he will have sufficient influence to neutralize, at least partially, the very strong anti-Polish trends within the O.W.I., especially in light of the pro-Soviet attitudes of the group of Polish citizens employed there whom I have described above.

Our pressure warned O.W.I.’s pro-Soviet elements that they cannot continue their bias with impunity. Our careful monitoring of O.W.I’s actions will determine our future actions.

Signed

J. Ciechanowski

Ambassador of Poland

1943

Capitol Stuff

By John O’Donnell

Times-Herald, Washington, D.C., August 20, 1943

“The misnamed Office of War Information has apparently decided to end its career by suicide and this may be all for the best.

Few honest newspaper tears are going to be shed over the demise of an outfit which from birth was a New Deal Roosevelt propaganda body (as discovered by the last Congress which amputated its domestic claws) and throughout its career gave off the distinctly unpleasant stench of being a parking place for pay-roll patriots, political stumble bums and the incompetent sweepings of editorial rooms.”

(…)

“Freedom might well shriek if some of the descendants of that original liberty Pole [General Tadeusz Kosciuszko] were faced with these latest OWI questions to Americans with Polish names. … the questions are framed with a strictly pro-Russian slant, in our opinion.”

1943

NOWY ŚWIAT

New York, NY August 21, 1943

O.W.I OR F.B.I

AN EDITORIAL

American public opinion was shocked by an article by John O’Donnell in the Daily News about the mysterious investigation conducted by the OWI through the Denver University.

(…)

Americans of Polish extraction give expression to their thoughts on politics by the way of casting their votes on election day; they give expression to their feelings with their blood in Africa, Alaska, Guadalcanal, etc. They know more about Hitler and Stalin than the O.W.I. can or cares to tell them. To the theorists and propagandists of the O.W.I., Russia, the Russians, communism and Stalin’s designs are merely clay with which they are playing. To the Poles these are realities. Tragic realities indeed — not theories, not politics.

We have been watching O.W.I.’s disturbing meddling and mysterious activities among the foreign born groups and have repeatedly expressed our resentment and our worry over the reaction. We must bear in mind that the O.W.I. is a part of our Government; that the O.W.I. speaks in the name of America and acts in the name of our Government not only when addressing nations enslaved by Hitler, but also when meddling here at home.”

1943

In order to block media access to prevent the publication of negative stories about life in the Soviet Union, American officials in charge of Polish refugee orphans who had arrived in the United States in 1943 after fleeing Russia put them in a former detention facility for Japanese Americans at the Santa Anita U.S. Army training camp near Los Angeles. After a few days of quarantine, they promptly dispatched the entire group to Mexico, where they were placed in a refugee camp under an agreement reached earlier between Polish Prime Minister General Władysław Sikorski and the Mexican government. Sikorski had traveled to Mexico in December 1942, where he met with Mexican President Manuel Avila Camacho. The Polish-Mexican agreement called for providing assistance to several thousand Polish refugees from Russia, who were then held in temporary camps in Iran. Out of 37,272 civilians who were Polish citizens evacuated from Russia to Iran in 1942, 13,948 were children. 1,434, most of them children, eventually arrived in Mexico. The Polish children had to be transported from India on a U.S. Navy ship to a U.S. port to get to Mexico. Their transport and support were negotiated between the Polish Government-in-Exile, represented in Washington by Ambassador Jan Ciechanowski, and the Roosevelt administration.

In order to block media access to prevent the publication of negative stories about life in the Soviet Union, American officials in charge of Polish refugee orphans who had arrived in the United States in 1943 after fleeing Russia put them in a former detention facility for Japanese Americans at the Santa Anita U.S. Army training camp near Los Angeles. After a few days of quarantine, they promptly dispatched the entire group to Mexico, where they were placed in a refugee camp under an agreement reached earlier between Polish Prime Minister General Władysław Sikorski and the Mexican government. Sikorski had traveled to Mexico in December 1942, where he met with Mexican President Manuel Avila Camacho. The Polish-Mexican agreement called for providing assistance to several thousand Polish refugees from Russia, who were then held in temporary camps in Iran. Out of 37,272 civilians who were Polish citizens evacuated from Russia to Iran in 1942, 13,948 were children. 1,434, most of them children, eventually arrived in Mexico. The Polish children had to be transported from India on a U.S. Navy ship to a U.S. port to get to Mexico. Their transport and support were negotiated between the Polish Government-in-Exile, represented in Washington by Ambassador Jan Ciechanowski, and the Roosevelt administration.

The children who came from the eastern part of Poland, occupied by the Red Army in 1939, were not direct victims of Hitler’s Fascism; they were primarily victims of Stalin’s totalitarian Communism. Most of them never saw any German occupiers since they lived in the eastern part of Poland, which had been invaded and occupied by the Soviet Union. As the Polish American newspaper Nowy Świat pointed out in January 1944, they were arrested with their parents by the Soviets and sent to the Soviet Gulag.

“The OWI purposely omitted the explanation and has not added that these tragic children came from Russia, that they forgot to smile there, that they learned there of hunger and want, that they there learned of fear.”

“A careless reader may gain the impression that with the beginning of the war, some group of Poles started on their journey to America, and after four years, had reached this continent. Not a word about the fact that together with millions of Polish citizens this group of refugees which has now reached Mexico was deported from Poland by the Soviets and was kept by Russia under the most miserable conditions. But seeing the obvious is not a virtue with the OWI. That Office is not evidently free from fear. (Fear) before whom?”

NOWY ŚWIAT

DECLASSIFIED

Authority S – 78 – 11

EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT

OFFICE FOR EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT

OFFICE MEMORANDUM

TO: Mr. Alan Cranston

DATE: January 4, 1944

FROM: Paul Sturman

SUBJECT: Nowy Swiat and OWI releases

The Nowy Swiat of January 4, 1944 carries, on its editorial page the recent OWI release on “Polish Children refugees in America” and makes this editorial comment, freely translated:

“We are submitting this OWI article to our Polish readers as an example of the service Polish press receives from the Office of War Information. The observations of the American soldier on duty at Santa Anita, where Polish refugees en route to Mexico were housed, excited all. That is true. But the OWI purposely omitted the explanation and has not added that these tragic children came from Russia, that they forgot to smile there, that they learned there of hunger and want, that they there learned of fear. Freedom of fear… Polish children did not know of that freedom upon their arrival to America. But it also appears that neither

does the OWI know of this freedom. It is afraid to admit that these children reached America from Russia. It speaks of a four-year journey, which they completed fleeing Hitler.“A careless reader may gain the impression that with the beginning of the war, some group of Poles started on their journey to America, and after four years, had reached this continent. Not a word about the fact that together with millions of Polish citizens this group of refugees which has now reached Mexico was deported from Poland by the Soviets and was kept by Russia under the most miserable conditions. But seeing the obvious is not a virtue with the OWI. That Office is not evidently free from fear. (Fear) before whom?”

1942

NOTES:

- Eileen Egan, For Whom There Is No Room: Scenes from the Refugee World (NewYork: Paulist Press, 1995), p. 19.

- Dwight D. Eisenhower, The White House Years: Waging Peace 1956-1961 (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, 1965) 279.

- Allan M. Winkler, The Politics of Propaganda: The Office of War Information, 1942-1945, Yale Historical Publications : Miscellany 118 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978), pp. 70-71.

- Jan Ciechanowski, Defeat in Victory (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1947), pp.115-116.

- Ibid., p. 130

- Ibid., p. 130

- Ibid., pp. 130-131.

- Ibid., p. 131.

- Jan Ciechanowski, Ambassador, to John J.Mitchell, Chief Counsel, United States House Select Committee to Conduct an Investigation and Study of the Facts, Evidence, and Circumstances on the Katyn Forest Massacre, Paris, October 14, 1952, Select Committee on the Katyn Forest Massacre, 82 Congress, Record Group 233, “Individual File,” A – Re, Box 5; National Archives Building, Washington, D.C.

- Fischer, Benjamin B. (1999–2000). “The Katyn Controversy: Stalin’s Killing Field”. Studies in Intelligence (CIA) (Winter). Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- Jan Ciechanowski, Defeat in Victory , p. 161

- Ibid.

- Jan Ciechanowski, Ambassador, to John J.Mitchell, Chief Counsel, United States House Select Committee to Conduct an Investigation and Study of the Facts, Evidence, and Circumstances on the Katyn Forest Massacre, Paris, October 14, 1952, Select Committee on the Katyn Forest Massacre, 82 Congress, Record Group 233, “Individual File,” A – Re, Box 5; National Archives Building, Washington, D.C.

- Jan Ciechanowski, Defeat in Victory, p. 201.

- Ibid., p. 264.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 267.

- Loy W. Henderson, A Question of Trust: The Origins of U.S.-Soviet Diplomatic Relations: The Memoirs of Loy W. Henderson, ed. George W. Baer, Hoover Archival Documentaries 333 (Stanford, Calif: Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University, 1986), pp. 518-519.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- John O’Donnell, “Capitol Stuff,” Washington Times-Herald, August 20, 1943.