By Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

Soviet influence at Voice of America during World War II — documents and analysis

Soviet influence at WWII Voice of America

From VOA to communist regime journalist

Choices of VOA’s pro-Soviet journalist

VOA journalist marries Communists

A pro-Soviet propagandist at OWI and VOA

VOA communist partner Stefan Arski

Pro-Soviet collaborators at OWI and VOA

A VOA friend of Stalin Peace Prize winner

Among Soviet sympathizers at VOA

Critics of her communist influence at VOA

Was she VOA’s communist ‘Mata Hari’?

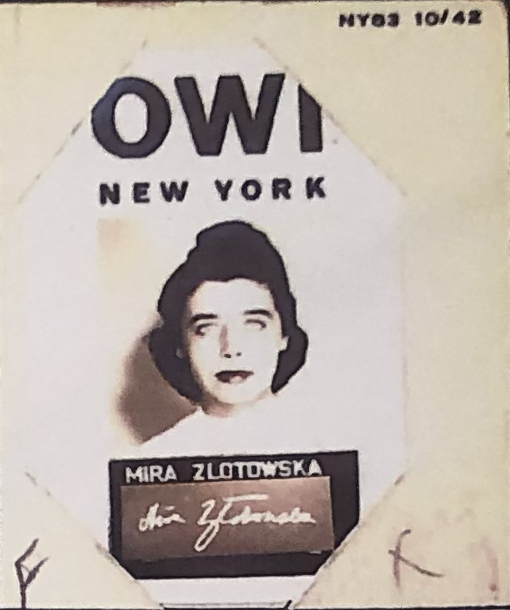

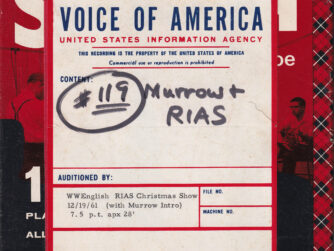

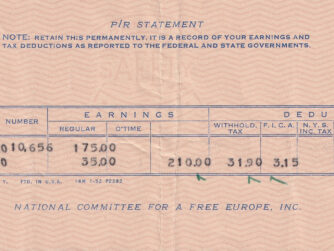

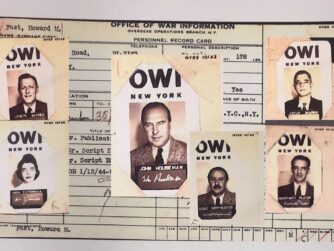

Mira Złotowska, later known as Mira Michałowska who published books and articles in English as Mira Michal and used several other pen names, was one of many radically left-wing journalists who during World War II worked in New York on Voice of America (VOA) U.S. government anti-Nazi radio broadcasts but also helping to spread Soviet propaganda and censoring news about Stalin’s atrocities. While not the most important among pro-Soviet propagandists at the Voice of America during the war, Michałowska later went back to Poland, married a high-level communist diplomat and for many years supported the regime in Warsaw with soft propaganda in the West while also helping to expose Polish readers to American culture through her magazine articles and translations of American authors. One of the American writers she translated was her former VOA colleague and friend, the 1953 Stalin Peace Prize winner Howard Fast who in 1943 played an important role as VOA’s chief news writer. Despite today’s Russian attempts to undermine journalism with disinformation, the Voice of America has never officially acknowledged its mistakes in allowing pro-Soviet propagandists to take control of its programs for several years during World War II. Eventually, under pressure from congressional and other critics, the Voice of America was reformed in the early 1950s and made a contribution to the fall of communism in East-Central Europe.

Refugees from Fascism and Communism

As the wife of the Polish communist regime’s ambassador, former Voice of America (VOA) and U.S. government employee Mira Michałowska may have found some friends among left-leaning American intellectuals, a few magazine editors, and some rich American businessmen, but one group she could not convert to her side were the journalists hired after the war to work for the VOA Polish Service in Washington. A former communist regime’s reform-minded political analyst Daniel Passent wrote that in Britain and in the United, States Michałowska helped Polish journalists establish contacts and provided them with useful information. These would have been pro-regime journalists like himself and Michałowska who were allowed to travel abroad and could publish in Poland while others could not. Radio Free Europe reporters, some of them also talented writers of books, were banned from traveling to Poland during the Cold War. Some of the Voice of America reporters were banned as well. None of them could have their books published in Poland under communism.

Most Polish-American community leaders and Polish World War II and Cold War refugees were well beyond Mira Michałowska ability to convert to the regime side even with her sophisticated and subtle propaganda of claims that the leaders in charge of Poland deep down wanted to be more liberal and wanted to welcome back any former refugee willing to alter his or her earlier opposition to communist rule. Failing to win over Polish political refugees to her point of view, she continued in the 1950s and the 1960s her work of changing the hearts and minds of somewhat more naive Americans to make them appreciate and support left-wing governments in East-Central Europe.

This was also her mission when she first came to America in 1940, herself a Polish-Jewish refugee from German-occupied Europe. While she was in France and in the United States, almost all of her Jewish family members in Poland are believed to had been murdered in ghettos or in German extermination camps. She also must have experienced anti-Semitism in pre-war Poland. What the Germans did in the Holocaust was the genocide of six million Jews—men, women, and children. About three million of them were Polish Jews. Her defenders believe that this explains and partly excuses her political choices during and after the war. According to Soviet propaganda claims, anti-Semitism had been stamped out in the Soviet Union and the imposition of socialism followed by communism in Poland and in other countries would guarantee that anti-Semitism would also be stamped out and would never return. Many naively believed these claims to be true.[ref]Piotr Oczko, “Wybór Miry. O Mirze Michałowskiej, Miesięcznik Znak, nr 769, June 2019.[/ref] She might have also accepted these communist propaganda claims at face value, but the choices she made as a journalist were ultimately tragic for both ethnic Poles and for Polish Jews who should have been warned not to trust Stalin and Communists seeking to establish a pro-Soviet government in Poland even if there were no viable alternatives to communist rule. VOA’s World War II broadcasts also turned out to be tragically misguided and misleading for Jews in Russia, although VOA did not broadcast in Russian until 1947, for more of them could have escaped when it was still possible during the final phases of the war. Jews in other nations which fell under Soviet domination were also misled. Hundreds of thousands of Poles stayed as refugees in the West because they were afraid of Communism. They knew better and could not be fooled by Soviet propaganda if they ever listened to VOA wartime broadcasts, but a few might have been convinced that it was safe to return to a country governed by Communists. Eventually, tens of thousands of Jews left the Soviet Union and the Soviet Block countries because they were afraid of both anti-Semitism and Communism.

Refugees from World War II and from Communism became the core of the post-war reformed Voice of America Polish Service and the Polish Service of Radio Free Europe. However, during World War II, anti-communist refugee journalists were not hired in any large number to produce Voice of America broadcasts, and if they were, they were quickly marginalized by their radically leftist colleagues and forced to resign by the pro-Soviet management if they wanted to avoid perpetuating the lies of Stalin’s propaganda.

Victims of history or victims of their choices?

Various explanations have been advanced as to why journalists like Mira Złotowska and Stefan Arski chose to support the establishment of pro-Soviet regimes in East-Central Europe. What they saw was the mass extermination of Jews and for reasons still difficult today to explain fully they associated ideas of progressivism and protection of human rights with radical socialism and communism, Soviet Russia and even Stalin himself. During the war, they found a welcoming place at the Voice of America building in New York among Americans who shared their views about Marxism and its presumed benefits for humanity. The usual excuse given then and now was that when faced with rampant and deadly anti-Semitism in Europe and ugly racism in the United States, journalists and intellectuals had no choice but to align themselves with communist parties and the Soviet Union or allow right-wing dictatorships to triumph. A young person in pre-war Europe like Mira Złotowska, as a potential victim of nationalism and anti-Semitism, could only choose to declare herself a communist and support Soviet communism. It was a false choice promoted by Soviet propaganda, which even many supposedly sophisticated journalists, much older than her, embraced without questioning. The New York Times no longer brags about Walter Duranty, its Pulitzer-winning foreign correspondent who lied about Stalin’s crimes. In the past, The New York Times had acknowledged, albeit timidly, Duranty’s duplicity in his denial that millions of Ukrainians and members of other nationalities were starved to death or murdered by communists. The Voice of America has not yet reached a similar stage of admitting its past mistakes and in 2019 still hides its past links to its former communist journalists.

What is rarely mentioned also by mainstream media is that some progressive America and other Western journalists started to repeat propaganda messages of the left-wing dictatorship in Russia in their fight against right-wing dictatorships. It did not occur to them that an ideology calling for a political system of the dictatorship of the working class based upon class hatred and class struggle would give a single party an absolute power when its leader or leaders saw it as desirable or convenient to turn the state security apparatus against any other group, including Jews or Christians. All these journalists had to do was to study information coming out of the Soviet Union without being blinded by ideology. It was a major failure of critical thinking and honest reporting on their part and on the part of many other left-leaning American and European newspaper writers, editors and other members of the creative group of individuals who at that time shaped public opinion.

Luckily, not all liberal journalists were fooled by such communist and Soviet propaganda. The Congressional Record from the 1940s includes many newspaper articles, transcripts of radio talks and statements by members of Congress of both parties, some ultra-conservative and right-wing but also many moderate Republicans and Democrats, warning against a threat from Soviet Russia and the risks of appeasing Stalin. Unfortunately, these voices were in the minority and were largely ignored by the Roosevelt administration, especially when the United States and the Soviet Union were for a few years military allies fighting against Nazi Germany. A few ultra-liberal Democrats praised and defended Stalin, but they were in the minority. Today, in a sad and disturbing change, Putin is increasingly finding support among Republican politicians who seemed now more prone to be misled by his more sophisticated new version of pro-Russian, anti-U.S. propaganda. They would be wise to read some of the old articles in the Congressional Record about Soviet disinformation efforts in the 1940s and the subversion of Voice of America broadcasts.

Since history had proven past pro-Soviet American politicians and propagandists wrong and since VOA drastically changed its programming policy toward Russia during the Cold War, Mira Michałowska and Stefan Arski’s names and those of other communists and communist-leaning fellow travelers were no longer mentioned in public discussions, in newspaper articles or in scholarly books in connection with wartime U.S. government radio broadcasts. The fact that, together with their agency’s top officials, they had duped what later became a U.S. government-run news organization into supporting an ultimately hostile foreign power and a dangerous foreign dictator became such an embarrassment to various new American administrations and the station’s management that the story of their subversion of honest journalism had to be obscured and hidden. During the Cold War, this erased and forgotten history allowed Mira Złotowska and a few others like her to renew their soft power propaganda activities in the United States as agents of influence for communist regimes without being easily identified with their similar activities in the past. She cleverly used a different name for her articles written after the war for U.S. news magazines.

Part of what Złotowska and others like her were doing with their post-war propaganda was to counterbalance the influence of left-leaning and liberal refugee intellectuals who had made a different choice and stayed in the West or escaped later from Poland rather than be forced to align themselves with the regime implementing a murderous ideology. They included such great Polish writers of various ideological and religious backgrounds as Czesław Miłosz, Witold Gombrowicz (who decided to stay in Buenos Aires), Gustaw Herling-Grudziński (Rome, later Naples), Jan Lechoń (New York) and Marian Hemar (London). Those who left Poland rather than to continue to live under communism included Jerzy Kosiński (1956), Marek Hłasko (1958), Aleksander Wat (1959), Irena Krzywicka (1962), Sławomir Mrożek (1963) and Leopold Tyrmand (1965).

To her credit, Mira Michałowska tried to stay on friendly terms with some of them and met some of them. After the fall of communism, she translated Jerzy Kosiński’s novel Cockpit. What she could not do was to get the regime to lift the ban on publishing in Poland books by most of these authors, including Kosiński, who were viewed as overly political and dangerous. When Polish émigré writer Melchior Wańkowicz returned to Poland from exile in the United States and cosigned an open letter in 1964, protesting against the censorship, he was put on trial and sentenced to three years of imprisonment for “spreading anti-Polish propaganda abroad.” The sentence was imposed partially due to broadcasting of some of his works by Radio Free Europe, but it was not carried out, and he was ultimately released. His trial showed, however, that writers and journalists were expected to cooperate with the regime or face retaliation. Many of them participated in Radio Free Europe and Voice of America programs. Almost all of these refugee or émigré writers, with perhaps one exception, can be described as social and political liberals. Tyrmand was a conservative libertarian. A few of the most well-known writers who chose exile in the West rather than submitting to censorship in Poland were Polish Jews.

Czesław Miłosz was the most famous Polish writer and poet associated with socialist groups in pre-war Poland, who after a brief career as the regime’s cultural attaché made his break with it, condemned it and stayed in the West. He was one of the most liberal Polish writers of his generation. During the martial law in Poland, imposed by the communist regime of General Wojciech Jaruzelski in 1981, I convinced Miłosz to record his message to Poland for the film Let Poland be Poland produced by the United States Information Agency (USIA), which was at the time the parent U.S. government agency for the Voice of America. The VOA Polish Service, of which I was then in charge, broadcast the audio from Let Poland Be Poland. I also interviewed the Nobel Prize-winning author for other VOA broadcasts to Poland. Some of the interview focused on anti-Semitism in pre-war Poland. In commenting on the expulsion of thousands of Jews by the communist authorities in Poland in 1968, Miłosz said that for a country in which the Germans murdered almost the entire Jewish population, organizing the 1968 anti-Semitic affair was such a shameful act which brought infamy to the country that it would be difficult to imagine enemies who could have thought up a better action against Poland.[ref]”1984 Interview with Czesław Milosz on Polish-Jewish Relations,” September 19, 1984, recorded by Ted Lipien for the Voice of America Polish Service. Cold War Radio Museum, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/1984-interview-with-czeslaw-milosz-on-polish-jewish-relations/.[/ref]

I also interviewed for the Voice of America was Jan Józef Lipski, a longtime opponent of the regime who signed open letters protesting against censorship, organized help for Polish workers imprisoned for their participation in strikes, and in 1987 helped recreate the Polish Socialist Party. I remember that he had refused to meet for our interview at the luxurious and modern Hotel Victoria in Warsaw, built by the regime with Western loans. It was to him a symbol of the regime’s corruption as it was used by the regime’s own functionaries, their local and Western supporters and enablers. The hotel was also closely watched by the regime’s secret police. We met instead at the nearby pre-war Hotel Europejski. During one period of the martial law, Lipski was arrested and kept in a prison hospital because of his heart disease.

Some of the Polish Socialists who had refused to support the communist regime paid earlier even a higher price for their principled opposition to communism and Soviet influence. Interwar and World War II Polish Socialist Party politician Kazimierz Pużak was imprisoned in Poland and taken to Moscow for the show Trial of the Sixteen of Polish anti-Nazi underground leaders. He died in prison in Poland in 1950. Many liberal political leaders, writers and journalists, including many Socialists, and both Catholic Poles and Jewish Poles, had made quite different political and life choices than Mira Michałowska and Stefan Arski. Many American Progressives also made quite different choices than another early Voice of America journalist, American Communist Howard Fast. Others like Mira Złotowska and Stefan Arski chose a different path and did not substantially alter their choice.

Liberal or right-wing?

However, because of an intentionally created memory lapse about choices that these individuals made or choices that could have been made but were not made when confronting dangerous ideologies on the right and on the left, new generations of Voice of America leaders, editors and writers could not learn from the mistakes made during World War II. It is therefore not surprising that they still make some of the same mistakes today as they face propaganda and disinformation from Putin’s Russia. An important part of Russian propaganda message today is to divide America and Europe along the same lines promoted by Soviet propagandists at the time Złotowska and Arski were working on Voice of America broadcasts to Poland: one can either be a Fascist and be called a Fascist or be a believer in leftist ideas of Marxism and Socialism. There was no room for dialogue and compromise in that scenario. Everything was either black or white. There was no middle ground.

During World War II and perhaps early in the Cold War, the Soviet Union was to propagandists such as Michałowska and Arski who believed in socialism the only acceptable, albeit imperfect liberal model. They were entirely wrong on this point, but in their geopolitical assessment of Poland’s future they were right. Stalin was going to control Poland no matter what the United States and Great Britain would do short of going to war with the Soviet Union, which was not an option most people in America or in Britain would support. Stalin had the Red Army troops on the ground in East-Central Europe. Obviously, the entire population of Poland could not pack up their belongings and move to Western Europe and the United States. An argument could be made that by going back to Poland to work for the communist regime, some of the more Western-minded communists and communist sympathizers like Michałowska had a moderating impact on the system. It was a self-serving explanation that they had told themselves to justify their political choices. At the same time, they helped to perpetuate regime rule in Poland. There are no easy answers whether, ultimately, they did more harm or good with their media activities. While living in Poland, they could not tell the whole truth about the regime and the Soviet Union. When they were in the United States during the war, they also would not have been able to tell the whole truth because the pro-Soviet Voice of America management would not have allowed it. However, they also chose to lie and censor on their own. In America, they had many other choices which they did not make. In communist-ruled Poland, their choices were limited if they wanted to avoid risking poverty and repression, but many Poles, including Polish Socialists, made different choices. Even if some of them initially supported the regime for practical or idealistic reasons, many withdrew their support later when they realized that it helped to perpetuate its rule.

Putin’s Russia today no longer has a liberal appeal, but his aim now is to wage an ideological war and divide Western societies rather than to sell any particular ideology. Michałowska and Arski could serve as examples of what was wrong with their pro-Soviet ideological journalism in the first and middle part of the last century when the double threat of German and other forms of European Fascism, American racial segregationism and Soviet Communism desperately called for independent reporting, analysis and solutions that would not result in the death of millions of people and subject even more millions to several decades of virtual enslavement. The civil rights movement in the 1950s and the 1960s showed that Americans were capable of solving some racial problems through largely non-violent actions and protests. In a perversion of honest journalism, Michałowska, at least initially, was selling to Poles and Americans as liberal and progressive a Soviet political system which, while radically left-wing, also deserved to be called right-wing and repressive. There may have been no geopolitical alternative to the Soviet domination over the region immediately after World War II, but the regime in Poland should have been described by Michałowska as totalitarian, just as the Russian government headed by Putin today should also be described as being in charge of a right-wing authoritarian state. Instead, she deceived American readers by reporting that Poland was a country rebuilding itself under a progressive and law-abiding government led by forward-looking, progressive and liberal Communists and their socialist allies. Her book about diplomatic family life published in English in the United States in the early 1960s is a classic example of soft-power manipulative public relations unless her intention was to embarrass the communist regime by showing its apparatchiks living the life of aristocratic privilege. It is doubtful that is what she had in mind.

Ted Lipien was Voice of America acting associate director in charge of central news programs before his retirement in 2006. In the 1970s, he worked as a broadcaster in the VOA Polish Service and was the service chief and foreign correspondent in the 1980s during Solidarity’s struggle for democracy in Poland.