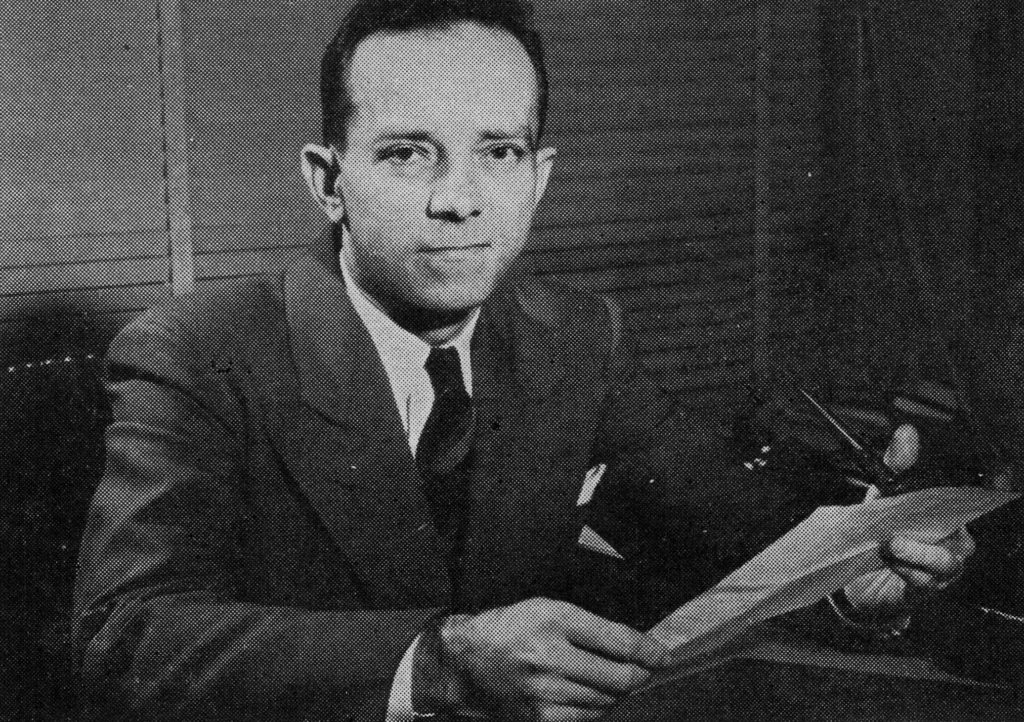

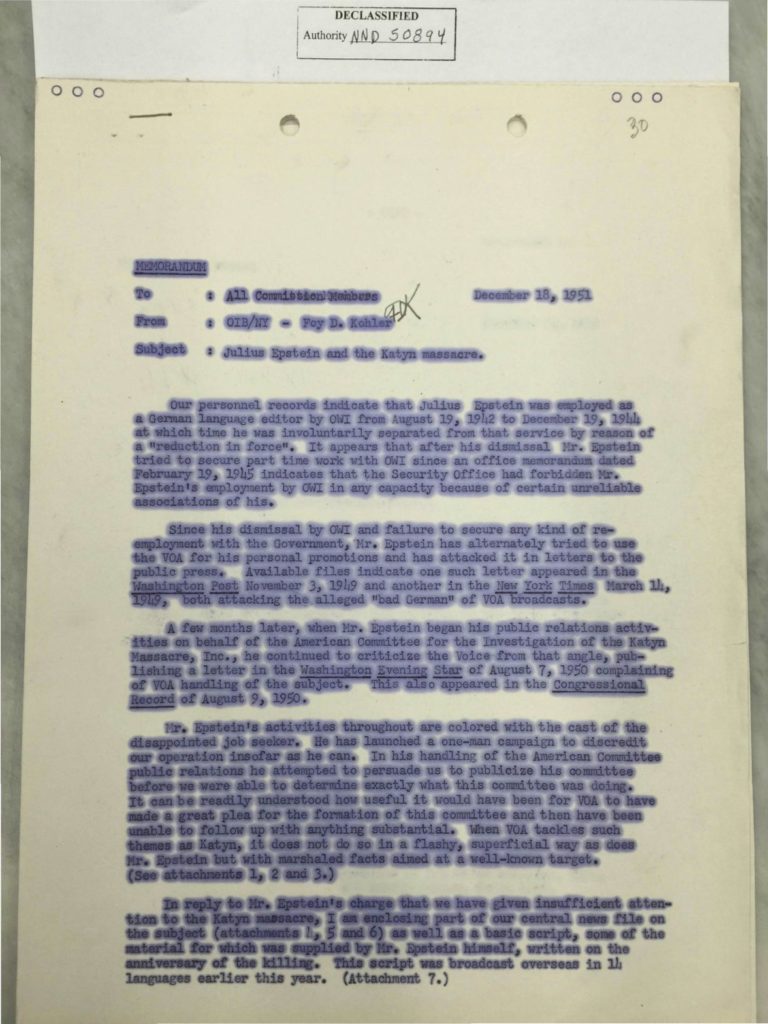

State Department diplomat and Soviet affairs specialist who was Voice of America director at the time (from October 1949 to September 1952), Foy D. Kohler, denied all the charges of Soviet propaganda influence within the Voice of America, made by former Office of War Information (OWI) German desk editor Julius Epstein, a World War II Jewish refugee from Nazi-occupied Europe, and proceeded to tarnish his reputation to contacts outside the U.S. government. In a memo dated December 18, 1951, which was declassified many years later, Kohler wrote that Mr. Epstein’s activities were “colored with the cast of the disappointed job seeker.” In the same memo, Kohler also suggested that Epstein himself should be investigated.

— U.S. State Department Diplomat and Voice of America Director (Oct. 1949-Sept. 1952) Foy D. Kohler

For many decades, the Voice of America’s U.S.-born senior managers discriminated against foreign-born VOA journalists and treated them as second-class citizens. In the early years, such discrimination was directed especially against those foreign-born journalists who, like Julius Epstein, held strongly anti-communist views. Epstein was himself briefly a member of the Communist Party in Germany in his youth before turning against Communism and the Soviet Union.

The Truman administration managed to lessen this type of discrimination and allowed refugee journalists greater independence in reporting on human rights abuses in the Soviet Bloc, but as late as the end of 1951, the VOA director, who was a career State Department diplomat, lashed out against a former Office of War Information German editor and internationally-published journalist for daring to expose the impact of Soviet propaganda on Voice of America broadcasts.

Finally, I cannot forbear adding that perhaps the time has arrived to investigate Mr.Epstein himself. His immigration status is not known but it is assumed he has become naturalized since taking out his first papers in 1942. His actions would seem to indicate that he is not be [sic] best type of new American citizen.

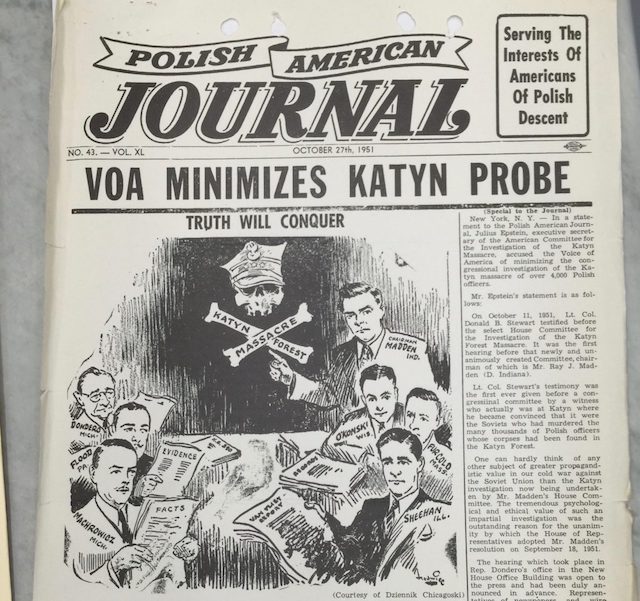

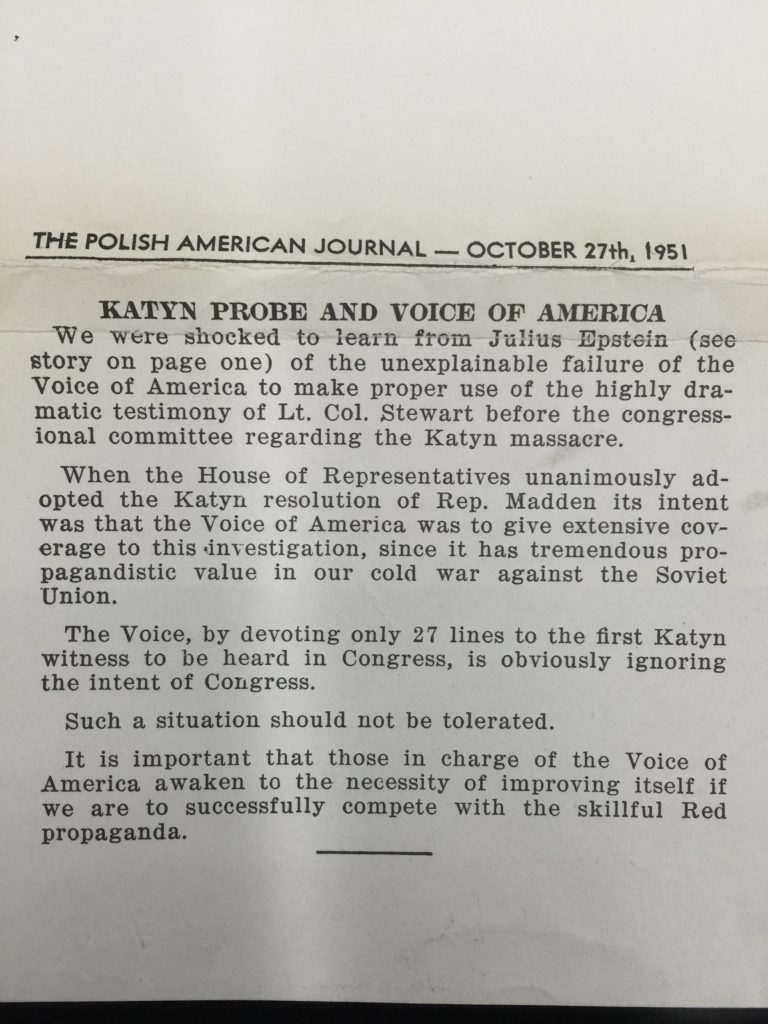

Despite assertions to the contrary from Voice of America officials, even as late as 1951, VOA still avoided full reporting on Soviet and other communist atrocities and provided only limited coverage of the initial stages of the congressional investigation of the Katyn murders. On October 27, 1951, the Polish-American Journal published an editorial, “KATYN PROBE AND VOICE OF AMERICA.”

We were shocked to learn from Julius Epstein (see story on page one) of the unexplainable failure of the Voice of America to make proper use of the highly dramatic testimony of Lt. Col. Stewart before the congressional committee regarding the Katyn massacre. When the House of Representatives unanimously adopted the Katyn resolution of Rep. Madden, its intent was that the Voice of America was to give extensive coverage to this investigation, since it has tremendous propagandistic value in our cold war against the Soviet Union. The Voice, by devoting only 27 lines to the first Katyn witness to be heard in Congress, is obviously ignoring the intent of Congress. Such a situation should not be tolerated. It is important that those in charge of the Voice of America awaken to the necessity of improving itself if we are to successfully compete with the skillful Red propaganda.”

One of the internal memos advised VOA officials to present Julius Epstein as “a disgruntled job-seeker who has proven himself to be an irresponsible promoter, an unscrupulous opportunist and a consistent liar.”[ref]”VOA CRITICS” Memorandum, Voice of America Historical Files 1946-1953 Reports-Psychologial Operations POC THRU Katyn Forest Massacres, RG59-Department of State-Entry#P315, National Archives at College Park, 8601 Adelphi Road, College Park, MD 20740-6001. [/ref]

Foy David Kohler (February 15, 1908 – December 23, 1990, a career Foreign Service Officer and a specialist in Soviet affairs, found himself under investigation when he and his wife were arrested in December 1952 for drunk driving near Washington shortly after his assignment as the VOA director. At the time of the arrest, he had with him two secret documents in violation of the State Department’s security regulations. The incident did not damage his diplomatic career.[ref]The New York Times, “Inquiry Is Begun on Acheson Aide: Kohler Had 2 Secret Papers When Arrested After Auto Wreck Near Washington,” December 2, 1952, page 18.[/ref] Despite his condescending attitude toward foreigners as demonstrated by his memo, he apparently performed well as an American diplomat in Moscow. After being nominated in 1962 by President Kennedy to be U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union, he served as one of the key liaisons with the Kremlin during the Cuban Missile Crisis and helped in a small way to defuse the threat of a nuclear confrontation, although the key decisions were made at the highest levels at the White House and at the Kremlin.

In response to criticism from Julius Epstein and others, Voice of America officials in the State Department denied that they were censoring the Katyn story. They pointed to what was VOA’s extremely minimal coverage until then as proof that there was no such censorship.

There was a VOA report on October 26, 1950, about the letter of former U.S. Ambassador to Poland Arthur Bliss Lane to Soviet Foreign Minister Andrey Vyshinsky calling on him to provide information about Katyn, but the report had only five and a half lines. This was typical VOA coverage on Katyn in 1949 and 1950 despite tremendous interest in the topic and severe press censorship in Poland, as well as in other countries under Soviet domination, and in Russia itself. Newly-established Radio Free Europe, which had no restrictions on Katyn coverage and much better news service about developments behind the iron curtain, quickly became the most listened to Western radio station in Poland.

In an attempt to hide their censorship, VOA officials also falsely claimed that a Polish officer, an outstanding writer, and artist Józef Czapski, one of the very few survivors of the Katyn murders and the person who had searched for the missing Polish officers in Russia whom Epstein mentioned in the excerpt inserted in the Congressional Record, had voluntarily agreed with the management of the VOA Polish Service to have references to Katyn eliminated from in his 1950 radio talk broadcast by VOA to Poland during his visit in the United States. Czapski was, in fact, pressured by VOA’s management and was outraged by the censorship. Several years later, he wrote about it in a private letter (1959) to Polish-American scholar Prof. J.K. Zawodny whose in-depth study of the Katyn massacre, Death in the Forest, was published by the University of Notre Dame Press in 1962.