by Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

On June 8, 1950, American novelist and Communist Party USA (CPUSA) activist and journalist Howard Fast, a former Voice of America’s (VOA) chief news writer and editor in the wartime United States Office of War Information (OWI), began serving his three-month prison sentence at Mill Point Federal Prison in West Virginia. Three years earlier, in June 1947, a federal court convicted him and ten other members of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee of contempt of Congress for refusing to give records of their organization to the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA). Quoting Henry A. Wallace, the former pro-Soviet U.S. Vice President during President Franklin Delano Roosevelt‘s second term, Fast accused the HCUA of Fascism, even though the committee under its various chairmen, Democrat and Republican, investigated both Communists and Fascists and monitored both Communist and Nazi propaganda. The HCUA and the U.S. Department of Justice considered the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee a subversive communist front organization serving the interests of Soviet Russia, but the defendants who were convicted and went to prison in 1950 claimed that they were only involved in helping Spanish refugees, mainly orphans and widows of those who had fought against the Franco regime in the Spanish Civil War.

Howard Fast was only one of many early Voice of America programmers and officials suspected of being Soviet and communist sympathizers, Soviet agents of influence, and, in a few cases, spies and intelligence contacts. There is no evidence to suggest that the Soviets recruited him as an active agent or spy. Still, he had emerged as one of Joseph Stalin‘s most important agents of influence in the United States during World War II and the early part of the Cold War. His loyalty to Communism and the Soviet Union was rewarded in 1953 when he received the Stalin Peace Prize. He joined the Communist Party in 1943 while still working for the Voice of America, radicalized by “his creative Communist colleagues at the OWI.”1 Fast would remain an admired figure among Communist Party activists and other left-leaning writers, journalists, and artists in New York and Hollywood. One of his extramarital affairs was with the future second wife of Alger Hiss, a State Department diplomat accused of espionage for the Soviet Union and convicted of perjury.

In 1957, Howard Fast publicly announced that he had left the Communist Party after Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev disclosed some of Joseph Stalin’s crimes. However, Fast did not return the Stalin Peace Prize he received in 1953, which included a substantial monetary award. Fast also did not apologize to the victims of the Stalinist regimes, which he had supported while they imprisoned, tortured, and murdered hundreds of thousands of real and imagined enemies and for decades kept entire populations, except the privileged Red aristocracy, in socialist poverty behind the Iron Curtain. His break with the Communist Party in 1957, described in his book The Naked God: The Writer and the Communist Party was lukewarm–not a total repudiation of violent Marxism and Soviet totalitarian Communism that other former Communists and fellow travelers, Louis Fischer, André Gide, Arthur Koestler, Ignazio Silone, Stephen Spender, and Richard Wright–presented much earlier (1949) and much more forcefully in their book of essays The God that Failed.

The support Communist Party members and Soviet sympathizers among American, British, French, Italian, and other Western journalists gave to a violent ideology based on class and religious hatred, and their willingness to ignore or excuse the aggressive nature of the regime in Russia had a significant impact on history. The support of left-leaning American journalists for the Soviet Union and their censorship of information about massive abuses of human rights in Russia allowed President Roosevelt to give in to almost all of Stalin’s demands without effective opposition in the United States and facilitated the post-war Soviet takeover of East-Central Europe.

Yet, despite his pioneer role as the Voice of America’s first chief news writer and editor, Howard Fast’s name and names of other Voice of America journalists and officials engaged in pro-Soviet propaganda have been erased from VOA’s official history–not unlike Stalin’s enemies among the early Bolsheviks who had disappeared from Soviet history books during his rule. These American fellow travelers are rarely mentioned in books and articles written by former American-born VOA directors and broadcasters, who seem to want to avoid causing embarrassment to the U.S. government’s media entity. Even though Howard Fast was a prolific writer who, during his career, had published more than 70 books and whose novel Spartacus was made into a Hollywood film starring Kirk Douglas, he is not mentioned in the official presentation of books authored by Voice of America employees. His name is not to be found in the often-cited Voice of America, A History by Alan L. Heil.2

As reported by the New York Times, Howard Fast and the other communist activists and anti-fascist progressives who went for several months to prison in 1950 after their conviction for contempt of Congress was upheld in U.S. v. Barsky told reporters that “they were victims” of the [U.S.] Government’s effort to support Fascist Spain in the ‘cold war’.”3 They were convicted before Senator Joseph McCarthy‘s (R-WI) anti-communist witch-hunt that targeted some individuals guilty of spying for Moscow and being Soviet agents of influence but also many who were innocent and acted in good faith in supporting civil rights and other progressive causes in the United States.

Still, many of them, including Fast, were duped by the Kremlin’s peace propaganda and, like Fast, refrained from any criticism of Stalin and his totalitarian regime. They opposed President Truman, the Marshall Plan, and NATO and supported former U.S. Vice President Henry A. Wallace, who had served under President Roosevelt from 1941 to 1945 and was the nominee of the new Progressive Party in the 1948 presidential election. In the spring of 1948, Wallace secretly met with the then-Soviet Ambassador to the U.N., Andrei Gromyko, to propose that he would travel to Moscow before the Democratic and Republican conventions to meet with Joseph Stalin. He also suggested that he and Stalin would issue a joint statement about “peace” with Russia to help Wallace in his presidential campaign. According to Fast’s biographer, “Fast agreed with Wallace in every instance,” including his condemnations of the Marshall Plan and the Truman Doctrine.4

Despite Wallace’s hopes, the Kremlin did not agree to his trip to Moscow and a meeting with Stalin, but the Soviet dictator responded to Wallace’s open letter to him, which he secretly sent to the Kremlin for review and editing before making it public.5

Following directives from the Soviet Union, the Communist Party USA and Howard Fast backed Wallace’s candidacy in his 1948 presidential campaign. Fast was the principal speaker at a pro-Wallace rally at Columbia University on April 16, 1948, at which he denounced President Truman, his Secretary of Defense James Forrestal, and the future Secretary of State John Foster Dulles during the Eisenhower administration as “obscene, hideous people who can sign a death warrant that will murder 50,000,000 people without a thought.”

Using a Nazi and communist propaganda technique of dehumanizing opponents, Fast said they “were no longer of the same species as you and I.”6

His biographer described Fast’s rhetoric as “a kind of unwitting warrant for murder.”7 Still, Fast would present himself later as a victim of Senator McCarthy’s anti-communist witch-hunts when in fact, it was the Democratic administration of President Truman that initiated court cases against Fast and other Communists and communist sympathizers suspected of membership in Soviet front organizations. Truman administration officials also eliminated them from various Voice of America positions in the State Department while hiring anti-communist refugee journalists to replace them.

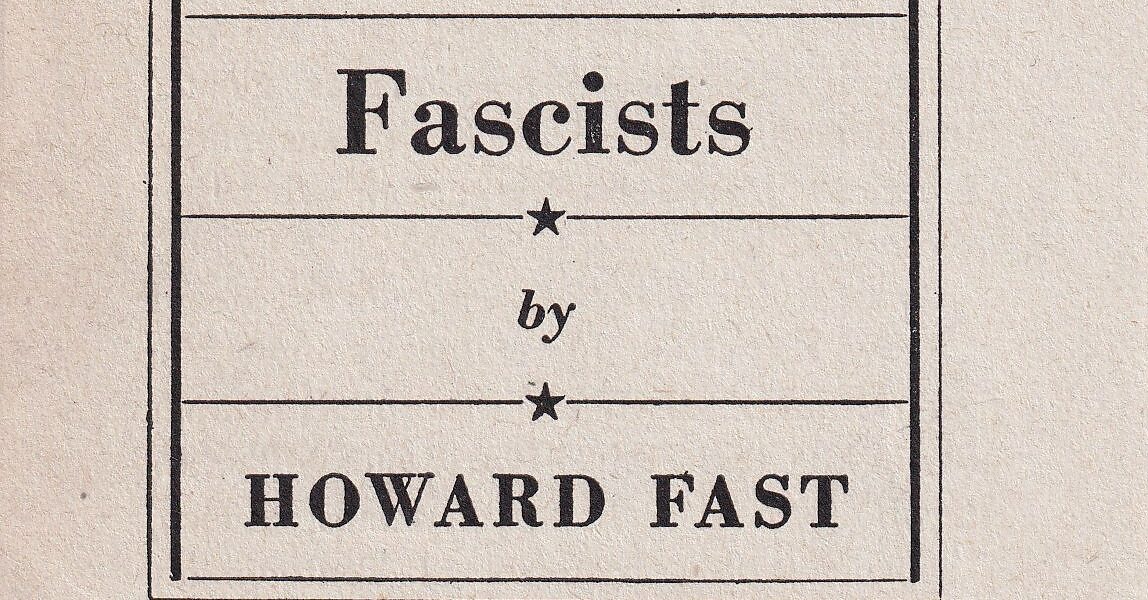

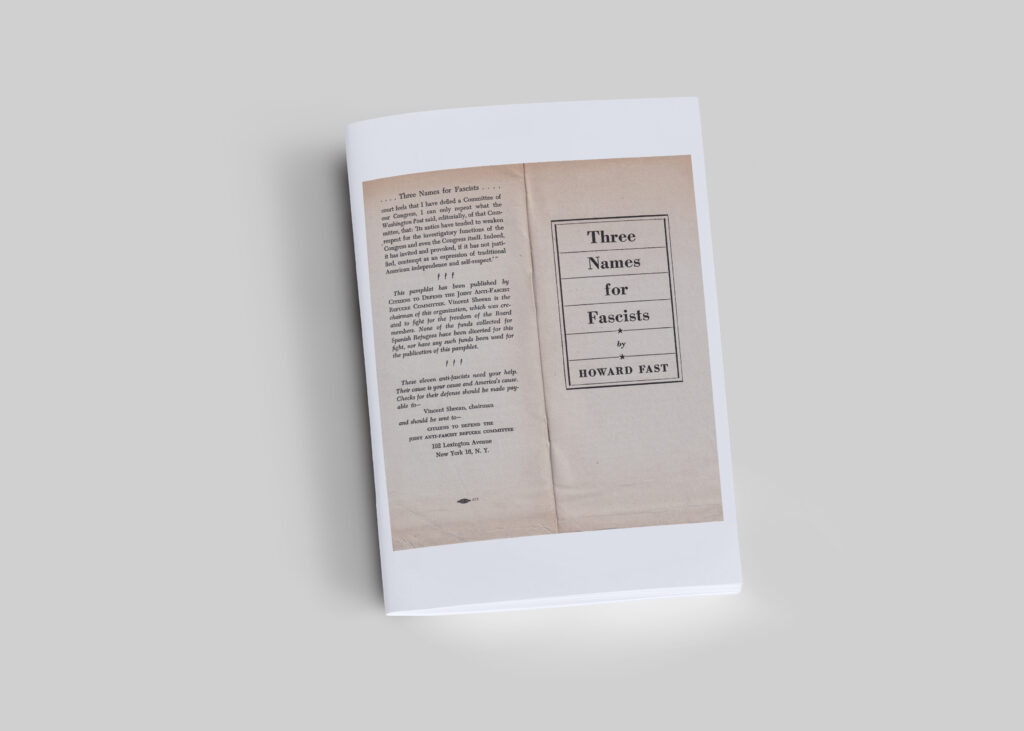

Another method of demeaning opponents was to accuse those who criticized Communism and the Soviet Union of being Fascists, nationalists, and reactionaries. Fast used such an attack in one of his propaganda pamphlets published in 1947 by quoting Henry Wallace. The attack was directed against members of Congress who were investigating Soviet influence within the United States government. In his pamphlet, Fast was defending himself and other members of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee convicted of contempt of Congress.

“I speak of only one source of shame to decent Americans who want their country to be admired by the world. I mean the group of bigots known as the Dies Committee–then the Rankin Committee, and now the Thomas Committee–THREE NAMES FOR FASCISTS the world over to roll on their tongues with pride.”

–HENRY A. WALLACE

WHEN eleven Board members of the Join Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee were given prison sentences of from three to six months, there were varying reactions in this America of ours. Progressives seemed to have been stunned into silence; reactionaries gloated, and through their press–which means most of America’s press–told the nation what they chose to tell.

Howard Fast, “Three Names for Fascists” pamphlet published by Citizens to Defend the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee, New York, 1947.

Supported by the Kremlin, the Communist Party USA and Howard Fast, one of the CPUSA’s most public figures, Henry Wallace lost spectacularly, receiving just 2.4% of the popular vote in the 1948 presidential election.

Supported by the Kremlin, the Communist Party USA and Howard Fast, one of the CPUSA’s most public figures, Henry Wallace lost spectacularly, receiving just 2.4% of the popular vote in the 1948 presidential election.

While working at VOA during World War II, Howard Fast followed in the footsteps of American and other Western fellow traveler journalists who reported on Soviet Russia in the 1930s. One of them was his boss, Joseph F. Barnes.8 In his autobiography, Being Red, published in 1990, Fast wrote that he kept “anti-Soviet propaganda” out of Voice of America’s World War II broadcasts.

As for myself, during all my tenure [1942-1943] there [the Office of War Information (OWI)- the Voice of America (VOA)] I refused to go into anti-Soviet or anti-Communist propaganda.9

VOA continued to protect Stalin for several more years after the war until President Truman, with bipartisan pressure and support from Congress, implemented management reforms at the State Department, where he had placed VOA in 1945. The Truman administration carried out personnel and programming changes that resulted in more forceful countering of Soviet and other communist propaganda from about 1951 onward.

Howard Fast’s biographer, Prof. Gerald Sorin, the author of Howard Fast: Life and Literature in the Left Lane (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012), for which he won the National Jewish Book Award, saw Fast and other pro-Soviet Russia American intellectuals and journalists of that period as misguided propagandists and censors for Stalin.

They failed to acknowledge the human inclination to abuse power, ignored horrific consequences, and often rationalized Soviet barbarities as historically necessary. One of the benefits of examining the life of Howard Fast is that it enables us to make yet one more exploration into the hoary question of how this could have happened.10

According to Prof. Sorin, Howard Fast got his job with the U.S. government’s Office of War Information, which included the Voice of America, thanks to Louis Untermeyer, an idealistic American poet and editor of Marxist magazines.

[Louis]Untermeyer, a former editor of the Marxist journal The Masses, who was writing propaganda pamphlets for the Office of War Information (OWI), suggested that Howard [Fast], instead of aimlessly wandering the streets, apply for the same sort of position. Fast was reluctant, never having done that kind of work before. But during his visit to the OWI building on Broadway and 57th Street, he was impressed with the people he met, especially Elmer Davis, the well-known writer and news reporter who directed the OWI; Joseph Barnes, veteran editor and foreign correspondent for the Herald Tribune, who (along with Walter Duranty of the New York Times), did much to put a veil of ignorance over the worst of Stalin’s crimes; and John Houseman, the [future] Academy Award–winning actor and filmmaker, who worked at the OWI for the Voice of America (VOA).11

According to Fast, there was no third way between Fascism and Communism, but even while he was still writing and editing news for VOA in 1943, American labor unions supported by the progressive wing of the Democratic Party stopped their collaboration with the Office of War Information over complaints that pro-Soviet Communists were in charge of VOA programming.

As noted by Julius Epstein, a Jewish-Austrian refugee journalist and writer who had worked at the Office of War Information during World War II and became later a longtime critic of pro-Stalin censorship at the Voice of America, the AFL-CIO, which in 1943 had refused to have anything to do with Communists like Howard Fast, was hardly a fascist organization. In 1943, when Howard Fast was in charge of Voice of America news writing and broadcasts to Europe, the two American labor federations, the AFL and the CIO, broke their collaboration with VOA in producing programs about the American labor movement, when they discovered that many VOA broadcasters were Communists. The mainstream American labor organizations were opposed to Communism. The controversy became public. Rep. Richard B. Wigglesworth (R-Massachusetts), who was later U.S. Ambassador to Canada, described it on the floor of the House of Representatives on November 4, 1943. 12

In his student years in Germany, Epstein was briefly a member of the Communist Party but left it and became a critic of Communism and Stalinist Russia. Before joining the Office of War Information in 1943, Epstein was an independent reporter for several major European and American newspapers and wrote about the threat from Fascism and Hitler’s Germany. He and his family left Europe for the United States before the Holocaust.

Unlike Epstein, Howard Fast was not a news journalist when he started his job at the Voice of America as the organization’s first chief news writer and editor, and neither was his patron, John Houseman, whose claim to fame before he was hired was his pioneer work as a producer of a fake news radio play in 1938 that duped many American radio listeners into believing in an invasion of the United States by aliens from outer-space.

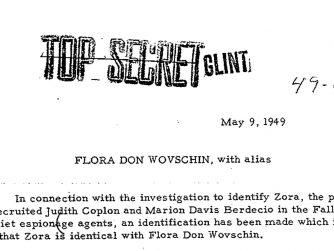

Howard Fast also did not speak any foreign languages to qualify him for work at the Voice of America. He was mostly known for being a bestselling author of historical novels. In his 1990 autobiography, he disclosed that he sought and received information from the Soviet Embassy for his World War II VOA broadcasts. Such embassy contacts would not have been unusual when the United States and the Soviet Union were military allies in the war against Nazi Germany, but Fast did not indicate that he had suspected his contacts of being Soviet intelligence operatives. Some of his friends among foreign journalists at the Voice of America were Soviet spies or were in contact with Soviet agents identified from secret Soviet cables by the U.S. counterintelligence Venona project.13 A few former OWI and VOA journalists, with whom Fast collaborated at VOA, joined East European communist parties after the war and became anti-American propagandists.

At that time, Fast was in charge of writing and editing the U.S. government’s radio programs for overseas audiences. They were not yet officially known under the Voice of America name, but some broadcasters at the Office of War Information were already using that name during the war.

I established contact at the Soviet embassy with people who spoke English and were willing to feed me important bits and pieces from their side of the wire. I had long ago, somewhat facetiously, suggested ‘Yankee Doodle’ as our musical signal, and now that silly little jingle was a power cue, a note of hope everywhere on earth…14

According to one description on the official Voice of America website, VOA adopted its “Yankee Doodle” station identification tune when John Chancellor was the VOA Director between 1965 and 1967 and had used earlier “Columbia, Gem of the Ocean,” but the information about Yankee Doodle being adopted by VOA in the 1960s may be wrong. Still, Fast’s claim of having proposed Yankee Doodle as VOA’s station identification music theme during World War II could not be independently confirmed.

In 1953, more than three years after serving his prison term for contempt of Congress, Howard Fast received the Stalin Peace Prize, later renamed the Lenin Peace Prize.

In his biography of Fast, Prof. Sorin leaves no doubt that he played a key role in writing news for Voice of America broadcasters, many of whom were Communists. According to Prof. Sorin, his new friends among VOA broadcasters were instrumental in bringing him into the elite group of communist and anti-fascist activists and the Communist Party, which he formally joined in 1943 while still working for the Office of War Information.

Fast wrote concise, dramatic pieces for broadcast, which were read by actors transmitting via BBC into Nazi-dominated Europe. … Eighteen of the twenty-three actors available for narration were Communists.15 Fast was not just “impressed” by them, he said, but “overwhelmed” by his associates “knowledge” and “sensitivity”.16

Communist broadcasters were hired by John Houseman, whose job was the chief of radio production, although he was later declared to be the first Voice of America director. The first program director at the Voice of America was another fellow traveler journalist, Joseph F. Barnes, who was a close friend of the New York Times Pulitzer Prize-winning Moscow correspondent Walter Duranty when both of them worked in the Soviet Union in the 1930s.17

They and nearly all other left-leaning Western journalists based then in Moscow hid most of Stalin’s atrocities from the American public and minimized the extent of the Soviet-engineered Holodomor famine in Ukraine that took millions of lives. One of them, Eugene Lyons, who in 1930 interviewed Stalin but later became disillusioned with Soviet Russia and Communism, wrote in an article in the June 1935 issue of Harper’s magazine titled “To Tell or Not to Tell”:

“Whatever happens,” I pledged in my own mind on my way to Soviet Russia, “I shall never attack the Soviet regime. No matter how disappointed I may be in the Bolshevik reality, I shall keep the disappointment to myself.”18

Even long after World War II and the Cold War, some members of the media community in the United States were still unwilling to admit that Walter Duranty did not deserve his 1932 Pulitzer Prize. The 2002-2003 Pulitzer Prize Board refused to revoke Duranty’s prize, claiming that while some of his reports were flawed, there was no evidence of deliberate lies in his reporting.19 A former Voice of America director and current (2024) U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM) CEO, Amanda Bennett, a group Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, was a member of the 2002-2003 Pulitzer Prize Board.20 As the successor U.S. government agency to the Office of War Information, the United States Information Agency (USIA), and the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG), the USAGM currently oversees the Voice of America and other U.S. government-funded international media entities.

Both Houseman and Fast were forced to resign from the Voice of America (Houseman in 1943 and Fast in 1944) when the State Department refused to give them U.S. passports for official travel abroad and secretly warned the Roosevelt White House about the hiring of Communists by the Office of War Information and their support for Soviet interests. Joseph Barnes resigned from his OWI and VOA position in 1944, after the New York Times reported about VOA broadcasts inspired by communist propaganda that could have put American troops in danger by criticizing General Eisenhower’s tactical deals with the French Vichy and Italian government officials, including Italy’s King Victor Emmanuel III, designed to shorten the war and save lives.

The ideological blindness and journalistic shortcomings of early VOA officials and broadcasters were profoundly dangerous. Supreme Allied Commander and later U.S. President General Dwight D. Eisenhower accused them of “insubordination” for endangering the lives of American soldiers with their pro-Communist and pro-Soviet propaganda.21

After the death of President Roosevelt in 1945, Howard Fast became a strong critic of all U.S. administrations, both Democratic and Republican. He supported Soviet and other communist propaganda peace offensives even after resigning from the Communist Party. In his 1990 autobiography, Fast repeated his earlier condemnations of post-war U.S. government efforts to stop further Soviet aggression and to counter Soviet propaganda. These actions included the creation of Radio Free Europe (RFE) and Radio Liberty (RL) to broadcast uncensored news and commentary to Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, but Fast wrote that the U.S. government also targeted Americans.

“…starting with the end of World War Two, the American establishment was engaged in a gigantic campaign of anti-Communist hatred and slander, pouring untold millions into this campaign and employing an army of writers and publicists in an effort to reach every brain in America.”22

In reality, because of the abuses by the Office of War Information in attempting to spread Soviet propaganda not only abroad through Voice of America broadcasts but also to propagandize directly to Americans, the U.S. Congress passed the 1948 Smith-Mundt Act to restrict the distribution of VOA and State Department programs in the United States while authorizing funding for U.S. public diplomacy and other information programs abroad. The Smith-Mundt Act also imposed much stricter security clearances for Voice of America staff.

Before he resigned from the Voice of America in January 1944, Fast had hoped that he would be transferred to North Africa, where new medium-wave radio transmitters were being constructed. Once they became operational, his job of writing radio news in New York would be eliminated. He received, however, bad news from the new VOA Director Louis G. Cowan, a future president of the CBS broadcasting network, that the State Department has refused to give him a U.S. passport for travel abroad because it suspected him of having strong Communist Party connections. The same refusal happened to John Houseman, which forced him to resign, but Cowan apparently did not want Fast to leave and offered him a job as a writer of propaganda pamphlets. According to Fast, Cowan also told him that the FBI had unmasked several card-carrying Communists on the Hungarian Desk, the German Desk, and the Spanish Desk. Fast was angry, declined the new job offer, and resigned to become more active in the Communist Party and pursue his journalistic and literary career outside the U.S. government. Louis G. Cowan also held radically leftist views, and pro-Soviet propaganda continued in VOA broadcasts under his directorship during the war. On January 21, 1944, he wrote a glowing recommendation letter for Howard Fast, in which he stressed that accepting his resignation was “pure compliance with your wish — not at all what we want.”

“…what a fine job you have done for this country, the OWI, and the Radio Bureau [the Voice of America] in particular….Please accept my own sincere thanks and with that the gratitude of an organization and a cause well served.23

Louis G. Cowan ended his letter to Howard Fast with a note that he was being grateful for his service at the Voice of America, not only on his behalf but also on behalf of Office of War Information Director Elmer Davis, Overseas Bureau directors Robert E. Sherwood and Joseph Barnes, and former VOA Director John Houseman. Many people at the agency “have been inspired by your sincerity and your achievement,” Cowan added. Josef Stalin had to be also among those pleased with Howard Fast’s performance at the Voice of America.

Several years after Howard Fast had left VOA and received his three-month prison sentence for contempt of Congress for refusing to provide names of members of a Communist front organization, he became a victim of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-Communist witch-hunt and blacklisting by Hollywood film studios. These actions were not directly related to his World War II work at the Voice of America. At that time, VOA was only of minor interest to Senator McCarthy, who in 1953 asked Fast only a few questions about his job at VOA and mainly concentrated on his membership in the Communist Party and the availability of his books at the libraries of U.S. embassies abroad.

Testifying on February 13, 1953, before the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations, chaired by Senator McCarthy, Fast refused to answer the question of whether he was a member of the Communist Party, claiming his rights and protection under the First and Fifth Amendments to the Constitution of the United States.

The Chairman [Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-WI)]. Have you ever been consulted by anyone in the Voice of America?

Mr. Fast. Now, I want to clarify this: You see, I know from the papers that this is a hearing on the Voice of America. I read that. When you say, “The Voice of America,” what do you mean?

The Chairman. Well, we mean just that, the Voice of America. Let us make it broader. Have you ever been consulted by anyone in regard to any of our government information programs, regardless of whether it is the Voice of America or any other government information program?

Mr. Fast. Consulted by someone?

The Chairman. Yes.

Mr. Fast. Yes, I have.

The Chairman. Who have you consulted with?

Mr. Fast. When you use the term “consulted,” I presume you mean discussed this question with me?

The Chairman. Yes, using it in its broadest sense, any discussion you have had with any of the people over in any of the information programs.

Mr. Fast. Various people who were a part of the Office of War Information, overseas radio division.

The Chairman. Will you name some of them? Name all those you can remember.

[Mr. Fast confers with his counsel.]Mr. Fast. Before I do that, I want to just clarify my position there. I worked in the Office of War Information.

The Chairman. How long did you work in the OWI?

Mr. Fast. I worked there, I believe, from November of 1942, from about November of ’42, to about November of ’43. That is a long time ago. My memory isn’t too certain on that. But I believe about then.

The Chairman. In other words, about a year?

Mr. Fast. About a year.

The Chairman. And I assume your answer would be the same as it was previously, but I will ask you the question anyway. At the time you were working in the OWI, were you a member of the Communist party?

Mr. Fast. I would have to refuse to answer that question for the reasons previously given.

The Chairman. Who hired you in the OWI? Who recruited you?

Mr. Fast. What do you mean “recruited”?

The Chairman. Well, would you just give us a description of how you happened to get the job in OWI?

Mr. Fast. I want to again preface my remarks by saying this is ten years ago, and I am not too clear. It is over ten years ago, and my memory would play false with me. But as I remember it, I was at that time living in Sleepy Hollow, New York, with my wife, the same one I am married to now, and I received my draft notification, and this gave my wife and myself reason to believe I would be drafted within the next couple of months. So we closed up our house in the country and moved into town. And I knew some people then who were working at the Office of War Information, and I dropped up to see them, and I said–

Senator [Henry M.] Jackson [D-WA]. Whom did you know?

Mr. Fast. Let me finish this, and I will go to that–to fill in this interim period, I would like to do some work with the Office of War Information, and, “How do I go about applying?” And I think I was told how I go about applying, and I simply applied. This, I think–I am very unclear about it because it was so long ago.

The Chairman. Mr. Jackson asked the question: Whom did you know there and whom did you consult?

Mr. Fast. Excuse me.

[Mr. Fast confers with his counsel.]Mr. Fast. You want to know who I knew before–

The Chairman. Yes. You told us a minute ago that after your draft notice came through, you knew some people in the OWI, and you went to see them and discussed with them the possibility of getting in the OWI. The question Mr. Jackson asked was: Who were those people?

Mr. Fast. Again, I must preface this by saying my memory is unclear, due to the length of time. I believe I knew, or else I knew by reputation, and he knew me by reputation, Jerome Weidman, the writer. Most likely by reputation. I don’t know whether I had ever met him before, as I remember it.

The Chairman. Jerome Weidman was holding what position in the OWI?

Mr. Fast. I don’t know, because this area of the Office of War Information into which I was brought to work, I remained in only a very short time, possibly only three weeks, and then I was transferred to the overseas radio division.

The Chairman. You said he knew you by reputation. At that time, did you have a reputation as a Communist writer?

Mr. Fast. I must refuse to answer that, too, on the same grounds stated before. But another point: Aren’t you asking me what another person thought?

The Chairman. You said he knew you by your reputation. I want to know what that reputation was. Was that your reputation as a Communist writer? And I am going to direct you to answer that question. You understand, Mr. Fast, that we are not asking you to pass upon whether that reputation was an earned reputation or not. Many people have a reputation which they do not deserve. The question is: What was the reputation?

Mr. Fast. You are asking me an exceedingly ambiguous question. You are asking me what my reputation was and I could not poll a reputation. In so far as I was aware of it at the time, my reputation….

[Mr. Fast confers with his counsel.]Mr. Fast [continuing]. My reputation was such as to cause me now, when I refer to it, not to mean certainly my reputation as a Communist writer. In other words, when I refer to my reputation, that Weidman knew me by, I was not referring to a reputation as a Communist writer.

The Chairman. I am not asking you at this time whether you were a member of the Communist party, but were you generally considered, in the writing field, in other words, did you have the reputation at that time, of being a Communist writer?

Mr. Fast. I think you would be more suited to answer that question than I would, don’t you?

The Chairman. Except that I am not under oath and not on the witness stand.

Mr. Wolf. That is an advantage sometimes.

Mr. Fast. I really can’t say. I just don’t know. I couldn’t say under oath, with any sense of clarity, what my reputation was eleven years ago. It was a reputation–I will say this–it was a reputation which was spelled out by Time magazine when they reviewed my book, The Unvanquished, and said that The Unvanquished was one of the finest American sagas to come out at the beginning of the war. Conceived in Liberty was reviewed everywhere throughout the country.

By the early 1950s, real Communists were long gone from VOA, and Senator Joseph McCarthy was chasing ghosts, mainly at the State Department. McCarthyism was a shameful episode in American history that claimed many innocent victims. If they did not work as foreign agents, writers, and journalists recruited by a hostile foreign government, they should not have been blacklisted. Still, Howard Fast’s support for Stalin and Communism at the Voice of America deserved to be more thoroughly investigated and exposed instead of being hidden by VOA officials and friendly journalists.

An appropriate punishment would have been exposure and moral condemnation of Fast, Barnes, and Houseman as a warning to future VOA broadcasters and radio listeners. Unfortunately, this did not happen. Fast’s blacklisting did not last long, and he quickly resumed his successful writing and publishing career. Meanwhile, millions of East Europeans, to whom Fast had tried to sell in VOA broadcasts the image of Stalin as a freedom-loving democrat, remained under brutal Soviet rule and a failing socialist economy for several more decades.

Fast eventually left the Communist Party in 1957, one year after Khrushchev revealed Stalin’s crimes, but he remained unapologetic about his promotion of Soviet “news” in VOA’s World War II broadcasts. His memoir Being Red, published in 1990, is a testimony to his ability to manipulate readers into believing that to fight Fascism, one had to become a Communist. For a journalist, he was supremely naive. In a 1998 radio interview, he described how staff members of the Communist Daily Worker cried when they read Khrushchev’s speech for the first time:

“And we heard this speech, and many of us wept. Because we did not know, and would not believe, the truth about the Soviet Union.

We had erected a Socialist state to our beliefs and to our dreams, and this for us was the Soviet Union.”24

The 2019 Voice of America online presentation “VOA Authors: Many Years – Many Stories – 75 Years of After Hours Wisdom” lists over 60 authors who had worked for the Voice of America over the years but did not mention Howard Fast–the author with by far the largest number of published books (several dozen), including bestsellers. He is also not mentioned in the introduction by former VOA Deputy Director Alan L. Heil Jr. (36 years with VOA) and Michele D. Harris (26 years). The VOA author featured in the presentation with the largest number of books (six) was Amanda Bennett, the then-VOA Director.

Former Voice of America Director Sanford J. Ungar, who served under President Clinton from 1999 to 2001 and is now Director of the Free Speech Project at Georgetown University, said in response to a question during a panel discussion on February 3, 2022, organized to commemorate the 80th anniversary of VOA’s first broadcast, that the news about Howard Fast receiving the Stalin Peace Prize in 1953, was merely “amusing.” Ungar implied that asking such a question about Fast’s links to the Communist Party could be proof of “McCarthyism” and that his critics were “white supremacists.” However, the most knowledgeable and honest critics of Soviet influence at the Voice of America were not right-wing “reactionaries”–there were a few, mostly among southern Democrats– but rather former communist sympathizers or even former Communist Party members who had turned against Soviet totalitarianism. Some of them, like Bertram Wolfe and Alexander Barmine, were well-respected journalists and writers who ended up working for the Voice of America during the Cold War.

Many moderate Republicans and northern Democrats in the U.S. Congress were also critical of Soviet propaganda influence at the Office of War Information and the Voice of America in its early years. Some of the other critics of the Roosevelt administration officials’ collusion with Stalinist Communism–Julius Epstein, Elinor Lipper, a young German-Jewish Communist who spent 11 years in Soviet Gulag prison camps, and Eugene Lyons–were political progressives and defenders of universal human rights. Many were Jewish and could hardly be accused of supporting Nazi white supremacy. Notable African Americans, writer Richard Wright, and journalist Homer Smith, also gave up their youthful fascination with Communism and condemned it. In his memoir, Black Man in Red Russia, Smith wrote about Stalin’s secret executions of thousands of Polish POW military officers, government workers, and intellectual leaders, known as the Katyn massacre, which the Voice of America started to cover up and falsely blame it on the Nazis while Howard Fast was writing VOA news.

However, while Fast was more than willing to protect Stalin from criticism, the order to censor information about the Katyn news story came from his superiors. OWI Director, broadcaster and journalist Elmer Davis, OWI and Voice of America executive and program manager Wallace Carroll, who became a news editor in the Washington bureau of the New York Times (1955-1963) and subsequently editor and publisher of the Winston-Salem Journal and Sentinel, and OWI and VOA freelancer-volunteer Kathleen Harriman Mortimer, the daughter of FDR’s wartime ambassador in Moscow W. Averell Harriman, actively spread Soviet disinformation to protect Stalin from accusations of ordering the massacre of thousands of Polish military officers captured by the Soviets in 1939.25

Another Office of War Information fellow traveler, Owen Latimore, was responsible for broadcasts to Asia, where China soon became a communist-ruled nation. As an OWI representative, he accompanied Vice-President Henry Wallace on his 1944 trip to Siberia, China, and Mongolia. After their return to the United States, in an article published in the December 1944 issue of the National Geographic Magazine, Latimore claimed that the workers in the Kolyma gold mines, visited by the American delegation, were volunteers of socialist labor, for whom special hothouses were constructed to grow vegetables so that they could be fed a vitamin-rich diet to keep them healthy and productive.26 While touring Siberia, Wallace and Lattimore never saw the prisoners of the Gulag slave labor enterprise. They were dying there by thousands from hard work, malnourishment, and untreated illnesses. The well-fed NKVD camp guards took the prisoners’ place for the duration of the American delegation’s visit.

In an article written in 1952, Wallace, whose quote Howard Fast used to accuse members of Congress of being Fascists, admitted that he was duped by Soviet propaganda.

More and more I am convinced that Russian Communism in its total disregard of truth, in its fanaticism, its intolerance and its resolute denial of God and religion is something utterly evil.27

Henry Wallace’s repudiation of Russian Communism in 1952 was considerably more honest than Fast’s criticism of Soviet and American communist parties in his 1957 book, The Naked God. Wallace met with Elinor Lipper and expressed remorse for being misled by Soviet officials about the Gulag. In The Naked God, Fast was incapable of offering a direct apology. If he did feel remorse for how his pro-Soviet propaganda may have contributed to the suffering of millions of victims of Communism, he tried to excuse his human and journalistic failures by self-pity over being deceived. In his 1990 autobiography, he mocked the Voice of America and resumed attacks on the Western Cold War institutions that helped to liberate East-Central Europe from Communism.

The obscuring of the pro-Soviet activities of the early VOA broadcasters, editors, and program directors prevented the organization from drawing lessons for protecting itself from pro-Russian, pro-Chinese, pro-Iranian, and pro-Hamas influence operations in the post-Cold War period. As students and followers of communist and Nazi propagandists, Russia’s Vladimir Putin’s regime, and the regimes in China and Iran, as well as Hamas terrorists, are exceptionally skillful in manipulating Western journalists on the right and on the left. Unlike the previous era, most American journalists and commentators duped today by Russian propaganda are on the right, most prominently Tucker Carlson,who failed to counter Putin’s lies when he interviewed him in the Kremlin. However, Russia, China, Iran, and Hamas also target left-leaning journalists.

The latest example of the effectiveness of the old Soviet propaganda techniques in today’s mainstream journalism is a recent refusal by a number of VOA reporters, editors, and managers to call Hamas “terrorists” while attempting to find excuses for the murder of defenseless Jews, including women and children, by citing Israel’s colonial occupation of Palestine.28 It is the same type of excuse for terror that Howard Fast and other fellow traveler journalists used for many decades to justify Stalin’s totalitarian rule and crimes against humanity. In the words of the Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times Moscow correspondent, Walter Duranty, who in his report titled “Russians Hungry But Not Starving,” published on March 31, 1933, tried to discredit Welsh journalist Gareth Jones‘ reports of mass starvation and millions of deaths in Soviet Ukraine and Russia as a result of the Bolsheviks’ forced collectivization of agriculture, “But – to put it brutally – you can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs.”29

The New York Times eventually mildly condemned Duranty’s “consistent underestimation of Stalin’s brutality.”30

The Voice of America will not even admit that Howard Fast, a Stalin Peace Prize winner, was one of its writers and editors.

NOTES:

- Gerald Sorin, Howard Fast: Life and Literature in the Left Lane, The Modern Jewish Experience (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012), p. 55.

- Alan L. Heil, Voice of America: A History (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003).

- The New York Times, “11 ‘Anti-Fascists’ Are Sent to Jail,” June 8, 1950, pp. 1 and 11, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1950/06/08/89735063.html?pageNumber=1.

- Sorin, Howard Fast, p. 160.

- Benn Steil, The World That Wasn’t: Henry Wallace and the Fate of the American Century, First Avid Reader Press hardcover edition (New York: Avid Reader Press, 2024), pp. 433-469.

- The New York Times, “1000 at Columbia Hear Howard Fast,” April 17, 1948, p. 9, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1948/04/17/86897354.html?pageNumber=9.

- Sorin, Howard Fast, p. 140.

- President Roosevelt’s close personal friend and foreign policy advisor, Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, warned the FDR White House in April 1943 about Barnes: “It is reliably stated that there has been no crucial point in Russian development, since 1934, when Barnes has not followed the Party line and has not been much more successful than the official spokesman in giving it a form congenial to the American way of expression.” State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944, From Collection: FDR-FDRPSF Departmental Correspondence, Series: Departmental Correspondence, 1933 – 1945 Collection: President’s Secretary’s File (Franklin D. Roosevelt Administration), 1933 – 1945, National Archives Identifier: 16619284.

- Howard Fast, Being Red (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990), p. 23.

- Gerald Sorin, Howard Fast: Life and Literature in the Left Lane (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012), p. 19.

- Sorin, p. 60.

- “MR. WIGGLESWORTH. I call as witness in this connection the American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations. I refer specifically to an article appearing recently in the World-Telegram. The gentleman from New York [Mr FISH] put the article in the CONGRESSIONAL RECORD, and you will find it in the RECORD of Tuesday, October 12, 1943, I shall not reinsert it, but here is the original of that article. You will notice the headlines. The leading headline is ‘Unions label O. W. I. radio program communism.’ That article very briefly asserts that the American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations made a joint protest over 10 months ago to Elmer Davis to the effect that the O. W. I. overseas branch had been regularly broadcasting Communist propaganda in its daily short-wave radio programs. It states further that after months of futile negotiation the A. F. of L. and C. I. O. liquidated their labor short-wave bureau set up to collect nonfactual news to be turned over to O. W. I. as broadcast material.”

- As a Professor of History at Emory University, Harvey Klehr, and a Library of Congress historian, John Earl Haynes, showed in their book Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America, secret Soviet intelligence messages monitored by the U.S. counterintelligence services as part of the World War II Venona project contained “the unidentified cover names of several Soviet espionage contacts in the Office of War Information,” including one in the OWI French section. John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America, Yale Nota Bene (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2000), pp. 197-199.

- Howard Fast, Being Red, pp. 18-19.

- Fast, Campenni interview, April 16, 1968; Fast on CBS Nightwatch, December 7, 1990.

- Sorin, Howard Fast: Life and Literature in the Left Lane (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012), pp. 45-46.

- In March 1939, Walter Duranty wrote in a letter to his American journalist friend John Gunther that he was angered by the Herald Tribune‘s decision to pull Joseph F. Barnes out of Moscow. Duranty thought very highly of Joe Barnes, describing him to Gunther as a journalist “who knows more about it [the Soviet Union] than anyone and was the best friend I had here, and lived quite near me.”S. J. Taylor, Stalin’s Apologist: Walter Duranty, The New York Times’s Man in Moscow (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), p. 280. Waler Duranty to John Gunther, 2 March 1939, Personal Files of John Gunther.

- Eugene Lyons, “To Tell or Not to Tell,” Harper’s, June 1935, p. 98.

- Pulitzer Prize Board, “Statement on Walter Duranty’s 1932 Prize,” November 20, 2003, https://www.pulitzer.org/news/statement-walter-duranty.

- Pulitzer Prize Board 2002-2003, https://www.pulitzer.org/board/2003.

- Dwight D. Eisenhower, The White House Years: Waging Peace 1956-1961 (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, 1965) 279. Also see Ted Lipien, “President Eisenhower condemned biased Voice of America officials and reporters,” Cold War Radio Museum, December 5, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/president-eisenhower-condemned-biased-voice-of-america-reporters/.

- Howard Fast, Being Red, p. 27.

- Howard Fast, Being Red, 25.

- Pacifica Radio’s Democracy Now, April 8, 1998, “Interview with Howard Fast,” https://www.trussel.com/hf/democnow.htm.

- For a journalist who has acquired such a stellar reputation, even eight years after the Katyn Forest massacre, Wallace Carroll still defended one of Stalin’s greatest propaganda lies as truthful in his 1948 book, Persuade or Perish, designed to teach Americans how to recognize and fight propaganda. Yet this fact is strangely omitted from his biography by Mary Llewellyn McNeil, Century’s Witness: The Extraordinary Life of Journalist Wallace Carroll, published in 2022, even though she devotes several pages to discussing his Persuade or Perish book. Century’s Witness jacket includes a quote from Donald Graham, former publisher of the Washington Post, saying, “Only after reading this wonderful book, did I understand how great Carroll was.” His biographer, however, failed to mention that Carroll was duped by Soviet propaganda. Mary L. McNeil, Century’s Witness: The Extraordinary Life of Journalist Wallace Carroll (Buena Vista, VA: Whaler Books, 2022). The Donald Graham quote appears on the front jacket above the title.

- Owen Lattimore, “New Road to Asia,” National Geographic, December 1944, p. 567.

- “Henry A. Wallace (1952) on the Ruthless Nature and Utter Evil of Soviet Communism,” Cold-War Era God-That-Failed Weblogging, a reprint of “Where I Was Wrong”, The Week Magazine, September 7, 1952, https://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2013/02/henry-a-wallace-1952-on-the-ruthless-nature-of-communism-cold-war-era-god-that-failed-weblogging.html.

- Ted Lipien, “Sometimes editorial ‘neutrality’ means propagandizing for totalitarians,” The Hill, December 29, 2023, https://thehill.com/opinion/international/4380310-sometimes-editorial-neutrality-means-propagandizing-for-totalitarians/.

- Walter Duranty,”RUSSIANS HUNGRY, BUT NOT STARVING: Deaths From Diseases Due to Malnutrition High, Yet the Soviet Is Entrenched. LARGER CITIES HAVE FOOD Ukraine, North Caucasus and Lower Volga Regions Suffer From Shortages. KREMLIN’S ‘DOOM’ DENIED Russians and Foreign Observers In Country See No Ground for Predictions of Disaster.,” filed March 30, 1933, published March 31, 1933, p. 13, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1933/03/31/99218053.html?pageNumber=13.

- “New York Times Statement About 1932 Pulitzer Prize Awarded to Walter Duranty,” 2003, https://www.nytco.com/company/prizes-awards/new-york-times-statement-about-1932-pulitzer-prize-awarded-to-walter-duranty/