By Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

On December 13, 1981, the communist government of the Polish People’s Republic subservient to Moscow introduced martial law and formed a military junta in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to crush the Solidarity (Solidarność) independent trade union movement. December 13, 2023 marks the 42nd anniversary of the mass arrests and further restrictions of human rights in Poland under communism. Before and after the imposition of martial law, Western radio stations broadcasting to Poland played a crucial role in providing uncensored news, interviews with dissidents, and commentary, which, in the end, enabled the Solidarity movement, supported by conservative and liberal intellectuals, the Catholic Church, and millions of ordinary Poles, to force the communist regime to give up power peacefully. Workers’ strikes and demonstrations brought about the fall of communism in Poland before the end of the 1980s decade. Other communist-ruled states in East-Central Europe soon followed Poland’s example.

Throughout this period, communist propaganda failed to garner popular domestic support for the pro-Moscow regime in Poland. It also failed to sway large segments of the population in the West. It may have provided, however, some encouragement to radical Western Communists and peace activists duped by the Soviet assertions of the supposedly peaceful and progressive Soviet Bloc countries being under alleged military threat from hostile governments of NATO members. NATO was strictly a defensive alliance and the only major military actions during the Cold War were Soviet-inspired invasions and conflicts, including the Korean War, the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956, the Vietnam War, and the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968.

The Polish communist regime’s attempts to win support for it among Western publics through external radio broadcasts is less known than Western radio broadcasting to the countries behind the Iron Curtain but should be studied to understand why it failed while Radio Free Europe, BBC, Voice of America, and other Western radio broadcasts were successful. Polish regime’s external radio programs, which were on the air both before and during the martial law, had a minimal impact and practically none after the imposition of martial law in Poland in December 1981. The difference between propaganda and reality in the end became too large to seduce even the most gullible leftist radicals in the West, with only a few exceptions.

Throughout the Cold War, communist propaganda and disinformation, repeated without adequate challenge in Western media by sympathetic, naive, or poorly-trained Western journalists, was many times more effective in influencing and confusing Western public opinion than direct radio broadcasts from Moscow or Warsaw. Western journalists could get propaganda messages directly from the Soviet TASS and other communist press agencies. In most cases, they did not have to rely on radio broadcasts from Moscow or Warsaw, but some did. While getting Western publics to support individual communist regimes did not work, communist pro-peace propaganda, amplified by some left-leaning Western intellectuals and communist front organization, had a considerable impact, particularly in Western Europe. During the Vietnam War, it also had an impact in the United States.

While engaging in propaganda, Polish Radio employed many talented journalists, some of whom were not at all supporters of the communist system but were restricted in what they could say on the air. They were forced to support the propaganda line of the communist regime even if they did not do it enthusiastically. Their public relations outreach was in some respects professional, especially when it promoted propaganda in support of communist peace offensives in the West, but in other respects was naive not very productive in terms of generating Western sympathy for communist regimes. By the 1950s, most radio listeners in the West with the exception of some fellow traveler intellectuals realized that communism in East Central Europe existed only because it was imposed by the Soviet Union and maintained by internal repressions.

The use by Polish Radio of Pablo Picasso’s “Dove of Peace” on their 1975-1976 promotional brochure may seem well-chosen for targeting Western communist sympathizers and left-leaning peace movement activists. Such direct propaganda was largely ineffective due to minimal listenership to Polish Radio’s external broadcasts in the West but was effective when picked up and spread by Western media. This phenomenon can also be seen today in Voice of America’s extensive reporting on calls on Israel to stop its military actions against Hamas while refusing to call Hamas fanatics “terrorists” and finding excuses to justify their murders of defenseless Jewish women and children. Pro-peace propaganda is one of the most effective weapons of violent and repressive groups and governments, especially if they can get Western media, artists, and intellectuals to support their propaganda.

The illustration on the November 1975-May 1976 Polish Radio promotional brochure is not a copy of the dove of peace drawing Picasso made on a napkin at a restaurant in Wrocław, Poland, where, in August 1948, he attended the World Congress of Intellectuals in Defense of Peace. It was a large propaganda gathering of Communists and communist sympathizers organized at considerable expense by Poland’s communist government.

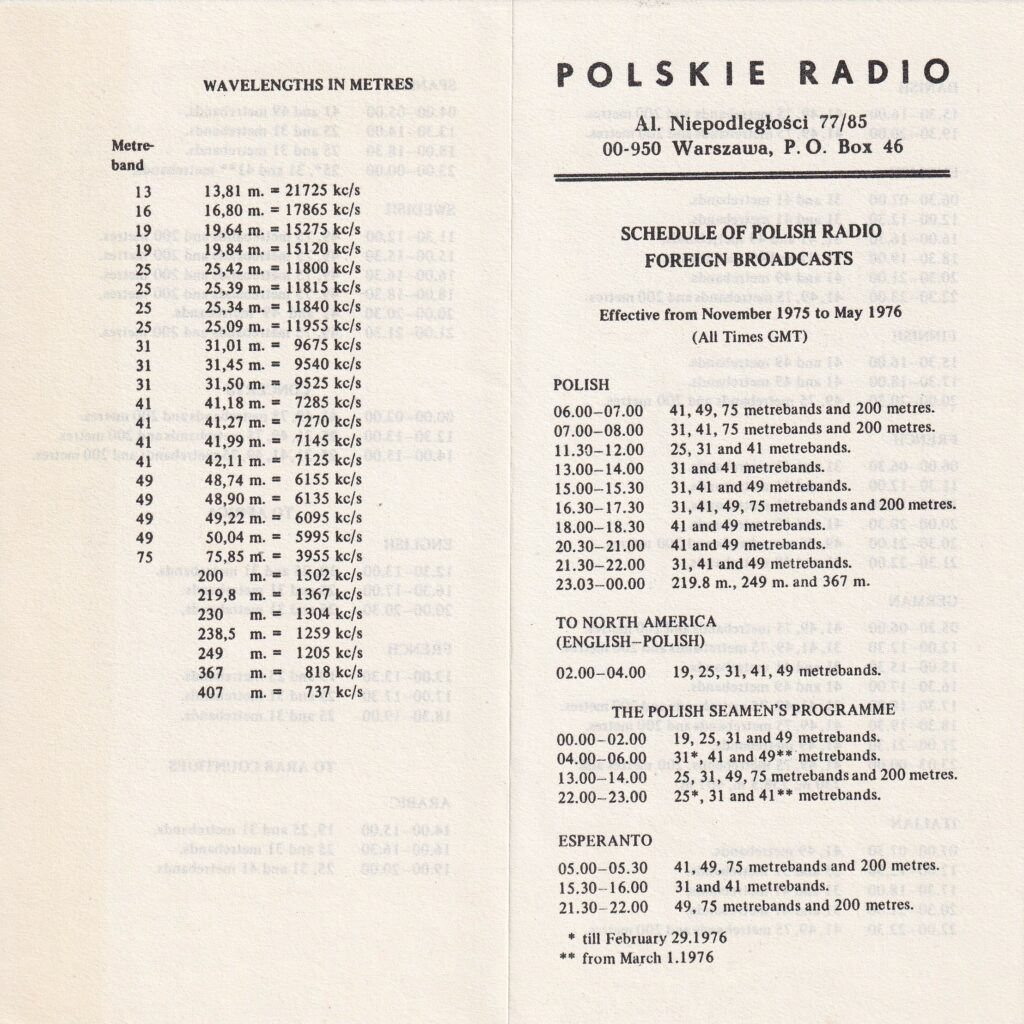

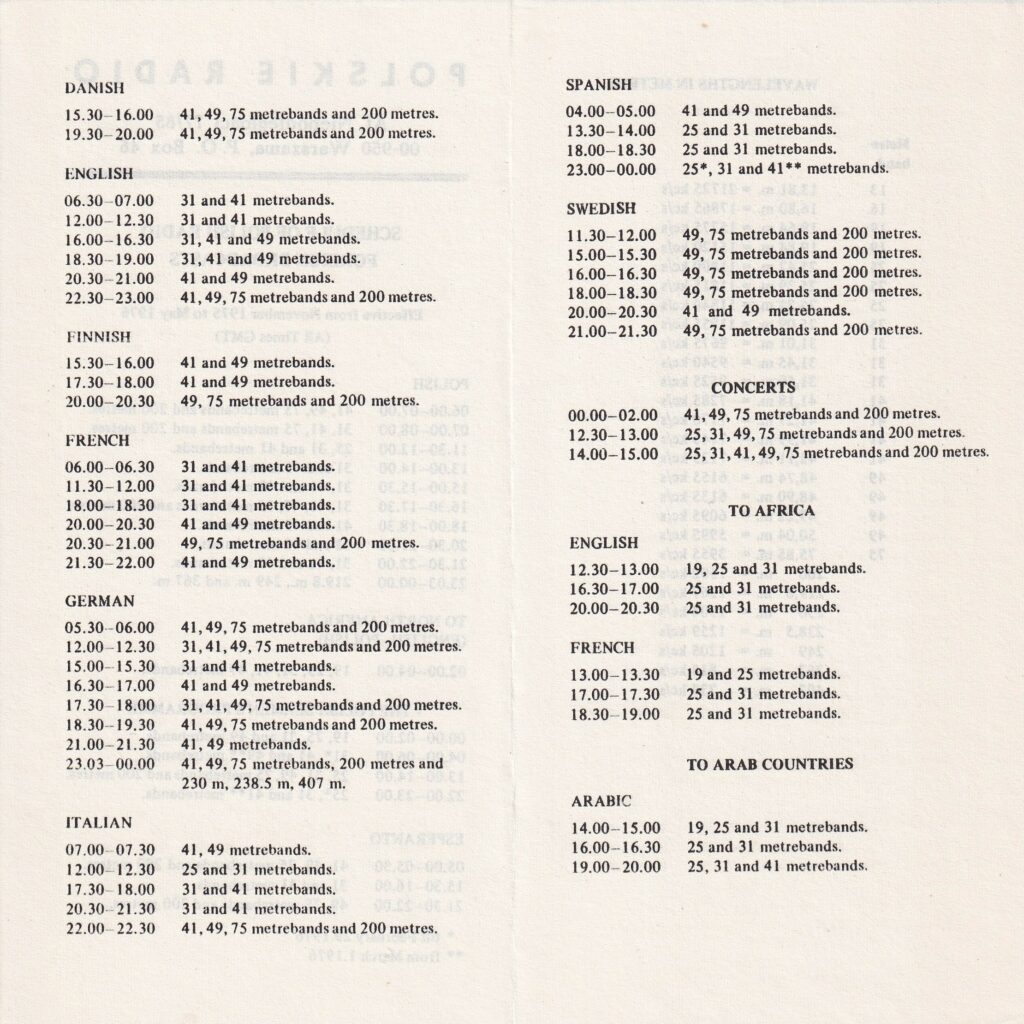

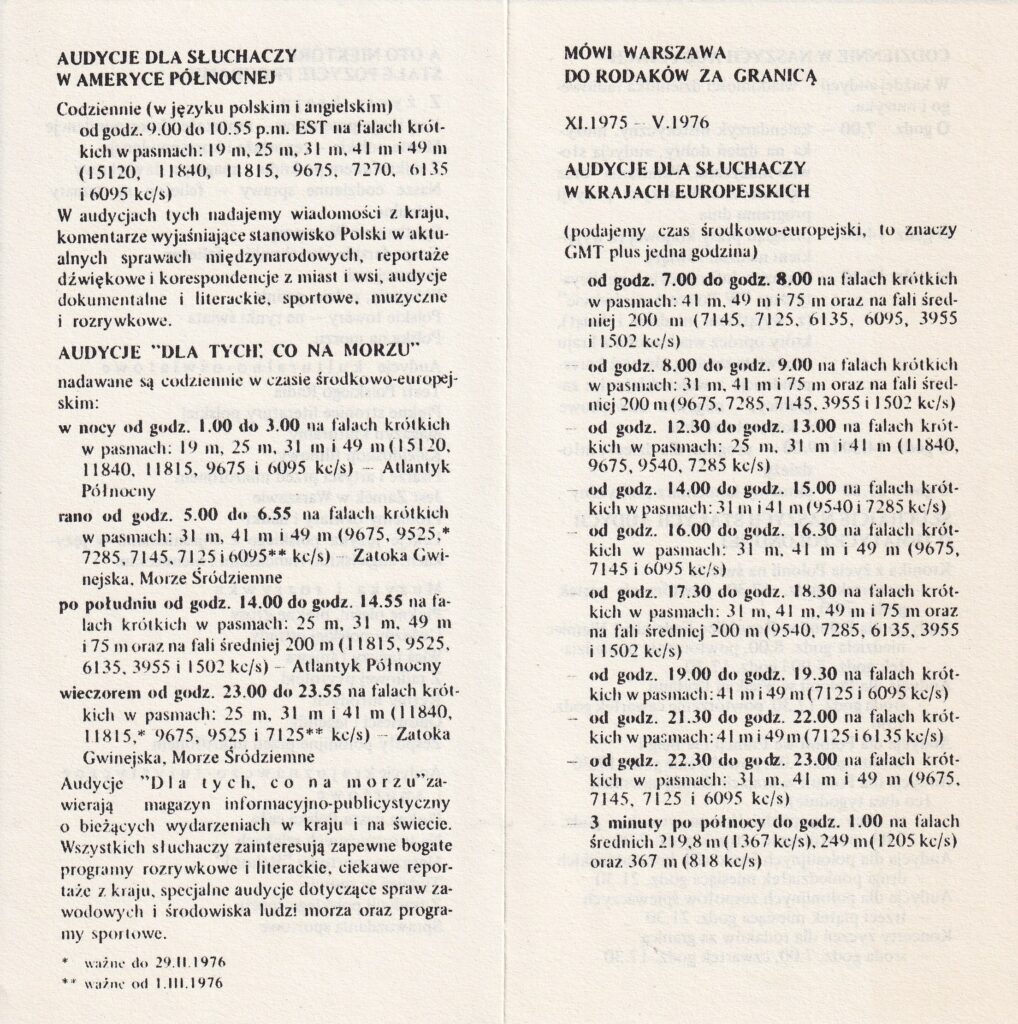

Polish Radio’s outreach to listeners in the United States was especially difficult due to long distance, inadequate shortwave radio signal, but most of all, the lack of a receptive audience. External radio programs from communist-ruled Poland to North America had almost no listeners among Americans of Polish descent. Refugee Poles living in the United States and second and third generation Polish-Americans were overwhelmingly hostile toward Poland’s communist government while, at the same time, being highly supportive of the Polish people. The vast majority of Poles living in Poland also strongly rejected the communist system imposed on them by the Soviet Union after World War II and in the 1980s sided by the Solidarity movement. However, until 1989, they were unable to change the system because of severe internal political repressions and the support for the regime in Warsaw from the Soviet Union.

Still, Polish-Americans wanted to maintain personal links with their families in Poland. They lobbied for American aid and trade with Poland as long as it could benefit mostly the Polish people rather than the communist regime. Polish Radio’s External Service tried to capitalize on these patriotic sentiments but had little success in attracting an audience in the United States, except for a few shortwave radio listening enthusiasts. These listeners were more interested in technical aspects of shortwave radio transmissions from abroad than in political propaganda. Some American shortwave radio listeners were, however, genuinely interested in learning more about Polish culture. Still, most were not eager to show any support for communism or the communist government in Warsaw.

In the promotional brochure published in 1975, Polish Radio offered to send their reporters to a village or town, from which a foreign listener’s family may have emigrated, and broadcast programs about these places, possibly including interviews with the listener’s relatives.

One must have a receptive audience to have an impact, which unlike the Voice of America and Radio Free Europe in Poland during the Cold War, Polish Radio did not have in the West. It was largely a wasted effort on the part of the communist regime despite a considerable expense to produce such programs. Ironically, Cold War communist radio broadcasts for foreign audiences may be compared in their limited impact with much of VOA’s programming today. Their originators found themselves on the wrong side of history. Whether VOA will also find itself on the wrong side of history by refusing to call Hamas “terrorists” and trying to excuse their genocide against Jews remains to be seen. Many Americans still hope that Hamas, along with its apologists, will ultimately find themselves on the wrong side of history.

The Voice of America today does not broadcast the same kind of programming in support of freedom and non-violent resistance as it did during the Cold War. One senior VOA reporter asked recently at a press conference in the White House whether President Biden may be “on the wrong side of history” because of his support of Israel. But if Hamas, Iran, and similar other radical groups and regimes are successful, as the Taliban was in Afghanistan despite nearly two decades of unrestricted Voice of America broadcasts to that country, they will win partly because of the tolerance of their violence and genocide, which much of Western media, including VOA, has shown in recent months and years.

Still, the Voice of America, and to a much greater extent Radio Free Europe and BBC, helped to contribute to the peaceful fall of communism in East-Central Europe. The final collapse of communism in the Soviet Bloc started first in Poland in the 1980s. I was then in charge of the Polish Service. Western broadcasters and journalists could learn from the success of these Cold War broadcasts, but many younger journalists are more likely to dismiss them as propaganda while regarding their own biased reporting today as objective and needed to support progressive causes and political parties on the left.

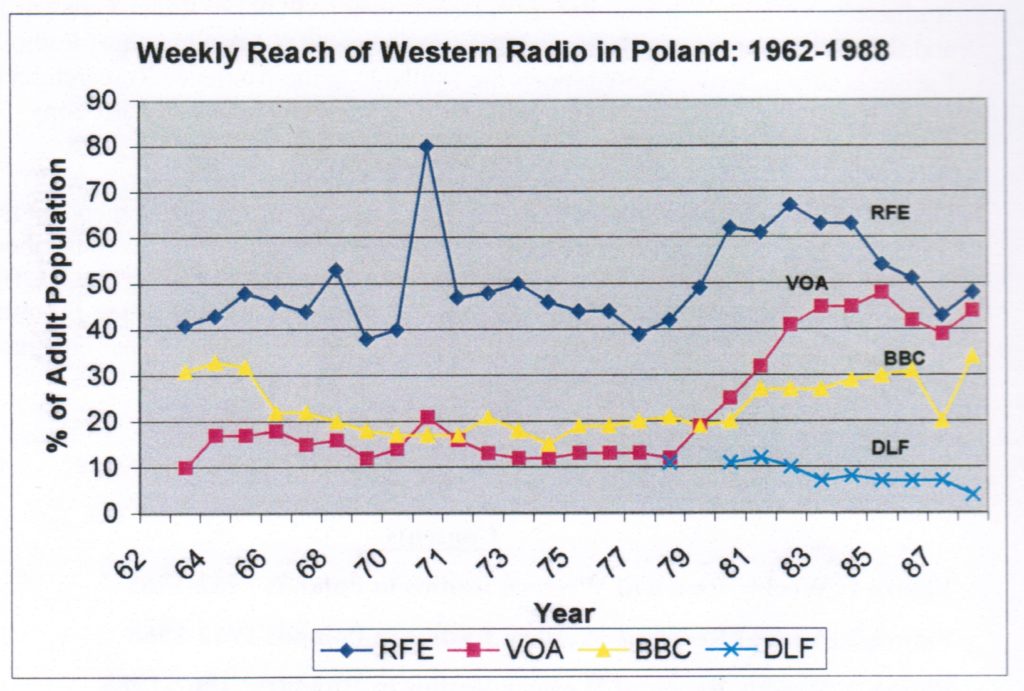

VOA’s audience to our Polish broadcasts grew almost fivefold in the 1980s, thanks partly to the support we received from the new VOA management put in place by the Reagan Administration. Imprisoned Solidarity activists were listening to VOA on radio sets smuggled to their internment camps. In the late 1980s, VOA Polish broadcasts were reaching weekly from 50 to 70 percent of the population, according to various surveys. The reach of Polish Radio’s external broadcasts in the West, including the United States, in English, in Polish, and in other languages was so low that it could not be measured.

While VOA Polish Service programs became very popular in the 1980s, listening to VOA English in Poland during the Cold War was insignificant. However, VOA jazz programs produced in English by Willis Conover had a small audience among elite anti-communist listeners in the 1950s. Later in the Cold War, VOA Polish and English services failed to attract a younger audience in Poland, as Radio Free Europe Polish Service did with its more appealing music and information programs. In the 1960s and the 1970s, VOA had only about a 10 percent weekly audience in Poland. RFE’s audience in Poland at that time was several times larger.

One of the problems Polish Radio faced was the extreme weakness of its shortwave signal in North America. The reception was better in Western Europe, but these broadcasts also had hardly any audience among the West Europeans, except perhaps for a few Communists and communist sympathizers. I tried listening to Polish Radio in the 1970s and the 1980s in the Washington, D.C. area. Most of the time, I could not hear anything, even with the best shortwave receivers and a good outside antenna.

Perhaps realizing that the listenership to their broadcasts was extremely low in the West, Polish Radio tried to promote tourist travel to Poland. However, most Western visitors to Poland during the Cold War became more anti-regime after being able to see the collapsing state-controlled socialist economy and as a result of their personal encounters with anti-regime Poles.

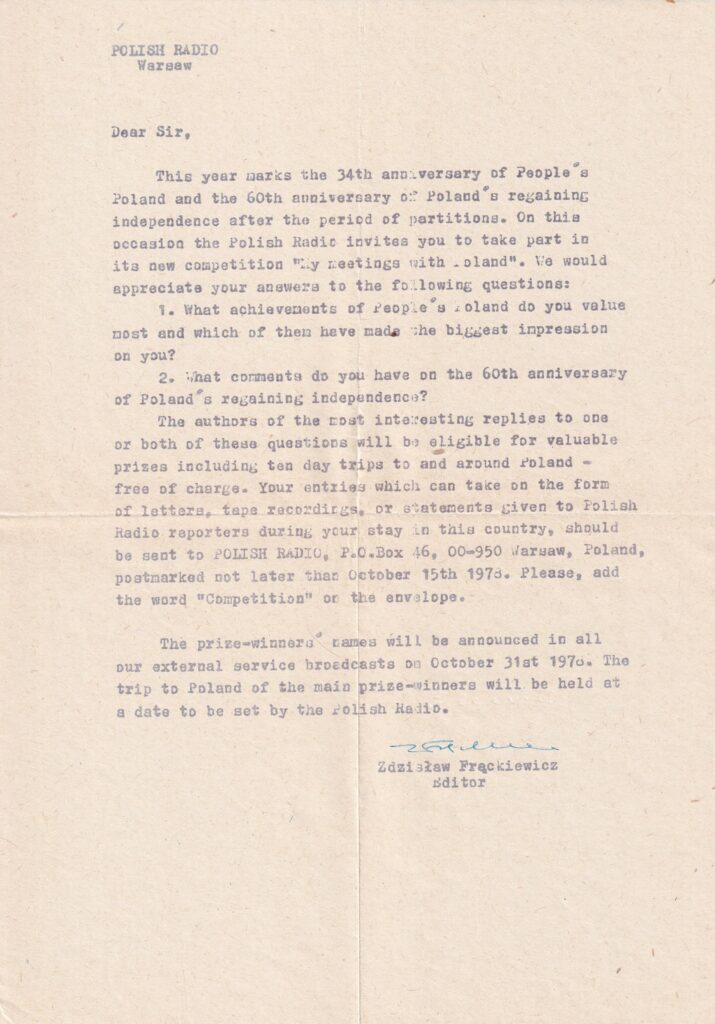

In a desperate move to generate interest in their external broadcasts, in 1978, Polish Radio announced a contest to mark “the 34th anniversary of People’s Poland and the 60th anniversary of Poland’s regaining independence after the period of partitions.”

Participants had to answer only one of the two questions to be eligible for winning prizes.

The first question was:

What achievements of People’s Poland do you value most and which of them have made the biggest impression on you?

A letter sent to a Polish Radio listener in the United States promised:

The authors of the most interesting replies to one or both of these questions will be eligible for valuable prizes including ten day trips to and around Poland – free of charge.

The letter said that “the prize-winners’ names will be announced in all our external service broadcasts on October 31st 1978.

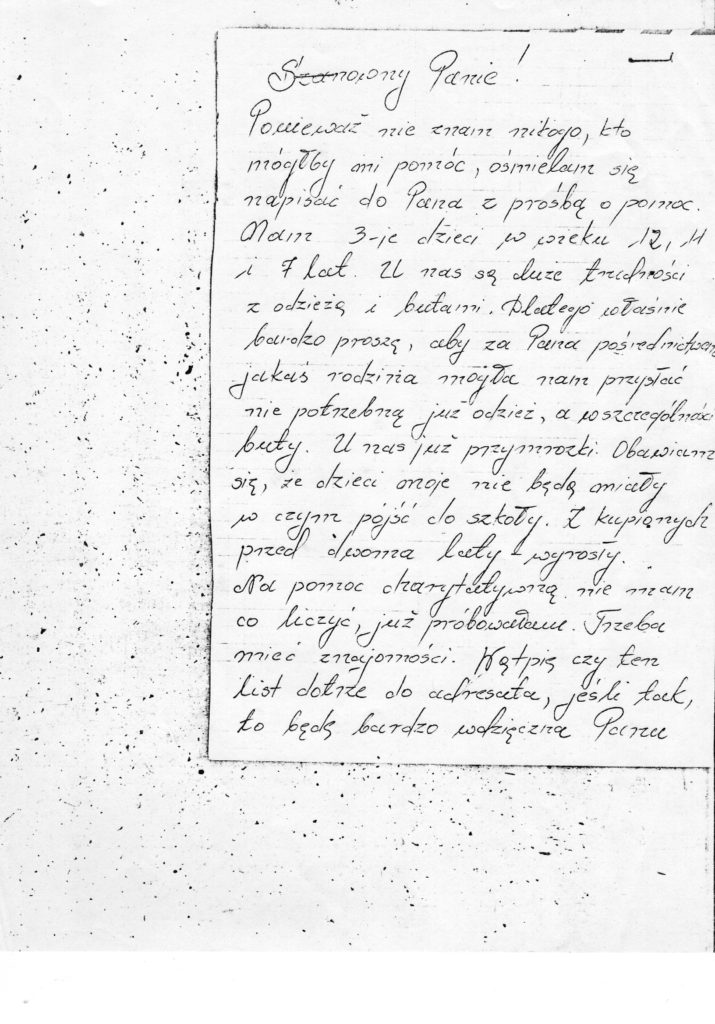

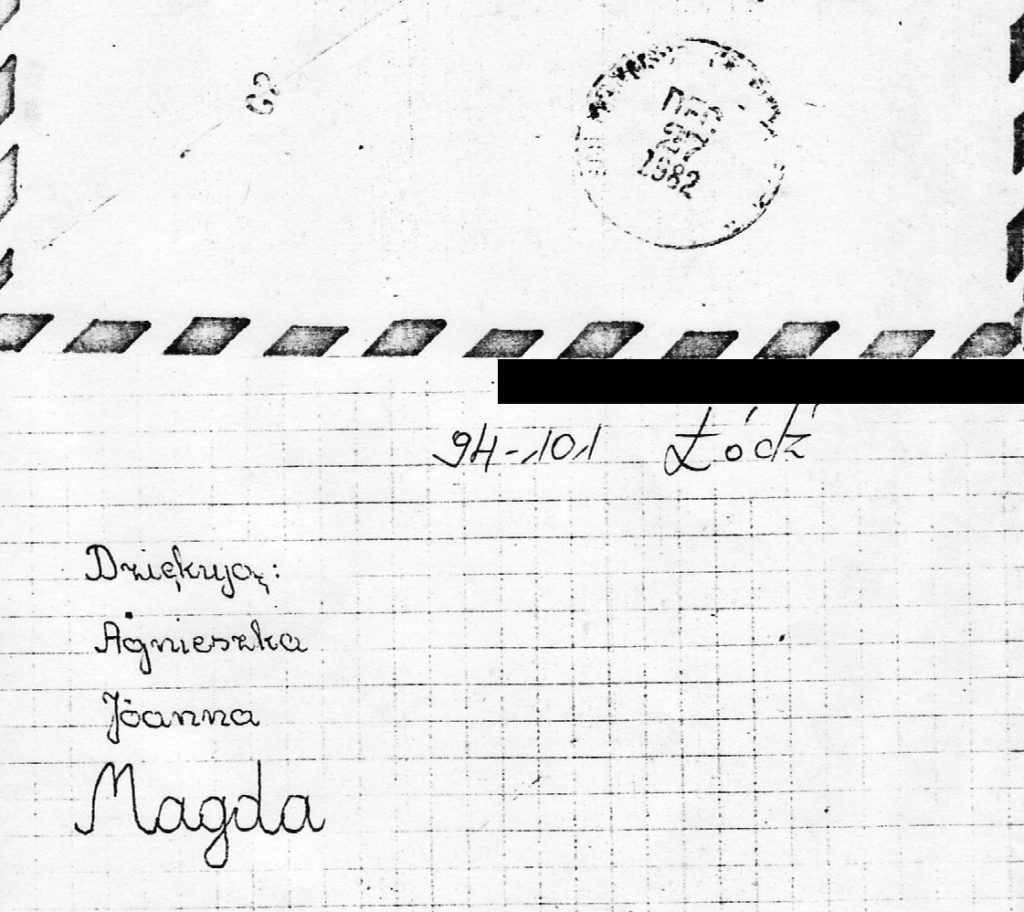

Radio contests could not overcome the futility of propaganda in favor of the communist propaganda in Poland. By the 1980s, it was apparent that the communist experiment in the Soviet Bloc had failed. VOA’s Polish Service received during the Cold War thousands of letters from its listeners in communist-ruled Poland with requests for humanitarian assistance. The number of such letters increased considerably in the 1980s. In one of them, sent to the Voice of America in November 1982 during the martial law in Poland, a Polish mother of three girls–Agnieszka, Joanna and Magda—ages 7, 11 and 12—asked if VOA could help her find an American family willing to send used clothing and shoes for her young children. All three girls signed their names on the letter. It was mailed from a city in central Poland. The majority of letters sent from Poland to the Voice of America during the Cold War with requests for humanitarian aid were written by women. Polish Radio’s external broadcasts could not erase the grim reality of centrally-managed state economy combined with political repressions, nor were they able to attract new listeners with their promotional brochures.

As money for international propaganda outreach dried out, the Polish communist regime still lashed out against the Voice of America broadcasts, which were becoming more and more popular in the 1980s.

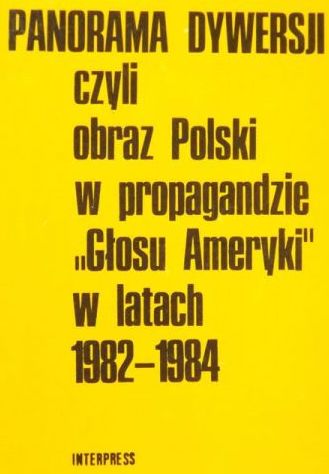

An article titled, “DYWERSJA ‘GŁOSU AMERYKI’ Polska na specjalny obstalunek” (‘Voice of America’ Sabotage: Poland by Special Order), appeared in the regional Polish Communist Party newspaper Głos Pomorza on Poland’s Baltic coast on January 9, 1986. It was a review of a book published by the Warsaw regime’s media agency Interpress under the title Panorama of Sabotage – Image of Poland in Voice of America Propaganda 1982-1984. Someone writing for the Communist Party newspaper under the name Kazimierz Adamski accused VOA Polish Service journalists of being saboteurs sponsored by Ronald Reagan and employed by the United States government. The communist commentator blamed us for trying to nullify the results of the 1944 Yalta Agreement, tearing out Poland from the alliance of socialist states and attempting to bring back capitalism. We were also accused by the author of the article and the authors of the book he reviewed of lying about dire political conditions in the country and about the crisis of Poland’s state-controlled socialist economy.

But even as communism was collapsing around them in the mid-1980s along with the state-controlled socialist economy, some regime journalists still published books and articles in Poland accusing the VOA Polish Service of anti-regime “sabotage.” I doubt that they did it because they believed it or that they were being paranoid. They produced their propaganda to collect their salaries for as long as they could from their communist media outlets. Voice of America’s dywersja or “sabotage” was, in fact, nothing more than what Solidarity leaders and human rights activists in Poland and abroad were telling our audience in Poland in telephone and in-person interviews. We did not have to lie nor would we under any circumstances.

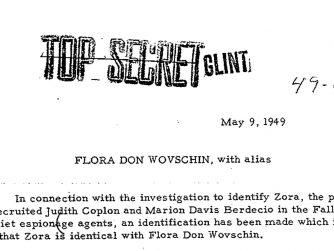

A note about me in the communist secret police file created in the 1980s said:

In his reports from the Polish People’s Republic, T. LIPIEŃ did not respect his own obligations because he concentrates on transmitting negative statements by the representatives of the opposition, previously recorded on tape, regarding the government’s policy and society’s mood. VOA then repeatedly broadcast these statements in the program “Echoes of the Day’s Events.” This is a special kind of “publicist” for the representatives of the opposition [to the communist rule].

I was especially proud when I saw in the communist secret police files their description of my work for the Voice of America. The file also included some inaccurate claims. The secret police exaggerated the number of professional contacts I had with the Polish Embassy in Washington (out of principle, I never attended any social receptions at Poland’s communist Embassy and went there only on VOA business, only with regard to visas for me and other VOA reporters). I reported these contacts to the agency’s security office, as all VOA employees were required to do at that time.

Polish secret police operatives were also wrong in reporting that I often interviewed a conservative opposition leader, Leszek Moczulski (I interviewed him and met him only once, at most twice, and at the same time conducted multiple interviews with much more influential opposition leaders, including Lech Wałęsa, the future President of independent Poland). They probably accurately noted that I had told the Polish Embassy that my reports from Poland would be objective and “not venomous.” However, they were wrong in thinking that I wanted to be a permanent VOA correspondent and a VOA bureau chief in Poland. The secret police also prepared a description of my family background and biographies of my parents. Much of the information in that report was factually wrong as their informants were not very reliable.

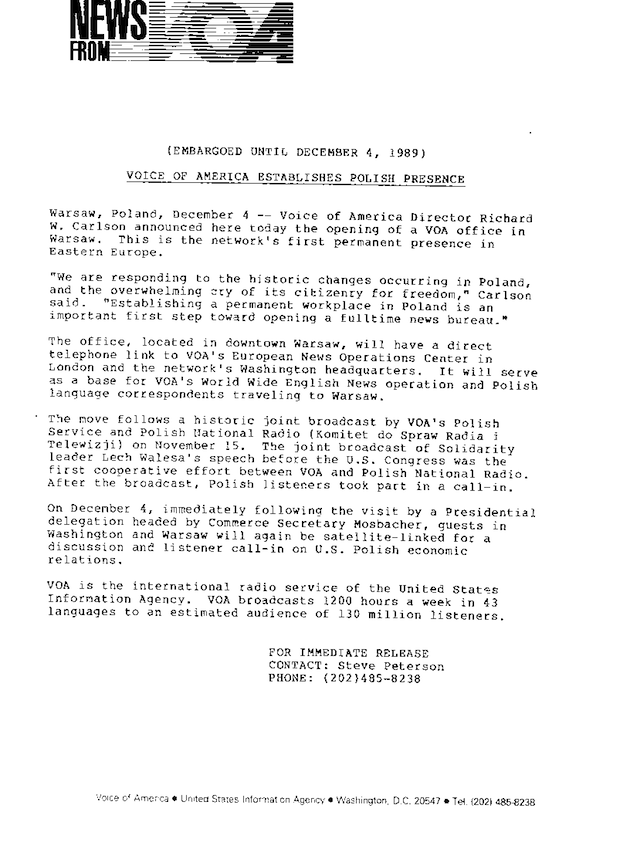

Soon after the fall of communism in 1989, I negotiated the first agreement establishing cooperation between the Voice of America and Polish Radio. In January 1990, radio listeners in Poland for the first time ever could hear Voice of America bilingual (English-Polish) live newscasts on Polish Radio’s nationwide network. This arrangement also marked the first time an Eastern European broadcaster had agreed to use VOA live newscasts. Already in March 1989, VOA Polish Service organized a similar program with Polish National Television in cooperation with Worldnet, which was then the television service of the United States Information Agency (USIA). I was the moderator of the joint VOA-Worldnet-Polish TV satellite broadcast with Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski. in January 1990, the VOA Polish Service and Polish Radio conducted a joint live news conference and a call-in program with Dr. Brzezinski. The Voice of America and Polish Radio stopped being ideological competitors.

I wish to thank Dan Robinson, former Voice of America White House bureau chief, foreign and domestic correspondent and VOA foreign language chief, for helping Cold War Radio Museum obtain these Polish Radio archival documents.