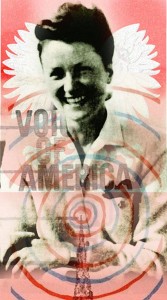

During the short tenure of Michael Pack, the United States Agency for Global Media (USAGM) CEO appointed by the Trump administration, the agency honored the former Voice of America (VOA) Polish Service editor and broadcaster, World War II anti-Nazi Polish Underground Army (Armia Krajowa) member, Zofia Korbońska, who died in 2010. Pack, a conservative anti-communist, and, unlike some right-of-center Americans who supported Trump, not duped by new Russian propaganda under ex-KGB President Vladimir Putin, agreed to issue a special press release in honor of Zofia Korbońska. The USAGM press release for the 10th anniversary of her death, requested by Ted Lipien, a former VOA Polish Service chief and a former VOA acting associate director, noted Zofia Korbońska’s struggle for freedom and democracy against Nazi and Soviet totalitarianism.

USAGM PRESS RELEASE, AUG. 16, 2020

USAGM honors the VOA Polish broadcaster Zofia Korbońska

August 16, 2020

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Today marks the 10th anniversary of the passing of Zofia Korbońska, a member of the anti-Nazi resistance movement who later immigrated to the United States as a political refugee from the Soviet Communism and long served the Voice of America (VOA) Polish Service.

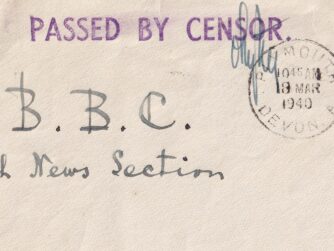

Born in Warsaw in 1912, Korbońska (née Ristau) was a member of the Polish Underground Army, which fought against the Nazis. Daily, she risked her life writing and coding secret shortwave radio transmissions sent from Poland to the Polish government-in-exile in London. A number of her dispatches that reached the free world were broadcast back into occupied Europe by the BBC. They broke news about Gestapo murders of the Polish intelligentsia, Nazi extermination of Polish Jews, and medical experiments on women prisoners at a concentration camp.

In addition to her clandestine radio work, Korbońska was also a partner in the work of her husband, Stefan Korboński, the leader of Poland’s anti-Nazi civil resistance and the last head of the Polish Underground State. (He was later honored in 1980 by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations for taking great risks to save Jews.) Shortly after the end of the Second World War, Korbońska and Korboński were arrested in Poland by the NKVD Soviet secret police but were released after several lengthy interrogations. Fearing another arrest, they escaped to Sweden in 1947, hiding in a ship transporting coal.

After they found refuge in the United States, Korbońska was hired by VOA in 1948 on the recommendation of former U.S. Ambassador to Poland Arthur Bliss Lane. She worked first in New York and later in Washington, D.C., using the pen name “Zofia Orłowska” to protect her family and friends in Poland. She continued to serve VOA for over three decades, writing and recording occasional programs in the 1980s even after her retirement.

In 2006, Korbońska was awarded the title of honorary citizen of the capital city of Warsaw. She also received from the president of Poland one of the country’s most prestigious civilian awards. She died in Washington, D.C. on August 16, 2010. Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski, National Security Advisor to President Jimmy Carter, delivered a eulogy at her funeral, in which he stated, “Zofia Korbońska – heroically brave in battle, prudent in political exile – was an example of what a dedicated and successful service in a great cause entails.”

The U.S. Agency for Global Media and VOA will always honor Zofia Korbońska and all of their journalists, past and present, whose reporting has advanced freedom and democracy.

Find out more

Contact Office of Public Affairs

- publicaffairs@usagm.gov

- (202) 203-4400

END OF USAGM PRESS RELEASE, AUG. 16, 2020

Zofia Korbońska – a Voice of America hero

By Ted Lipien

May 16, 2016

An interview on Deutsche Welle (DW), Germany’s international broadcaster that subscribes to high standards of journalism, reminded me of the late Voice of America (VOA) editor, writer, and announcer Zofia Korbońska. The interview was with a British journalist who wrote a book about World War II Nazi crimes against women. With great risk to her life, Zofia Korbońska helped to expose these crimes while they were taking place, and later while working for the Voice of America helped to expose Soviet crimes and Soviet propaganda.

Today, May 10, 2016, would have been her 101 or 104 birthday, depending on which date of her birth is used . The year listed on her false identity document in Poland under the German occupation was changed from 1912 to 1915 to confuse the Gestapo and was not corrected after the war to confuse the Soviet and the Polish communist secret police. It was still listed on her identity documents when she and her husband escaped from Poland to the West in 1947. It would have been too difficult to try to change it , and the wrong date remained on all of her official American records and was listed in her obituary.[ref]Roman W. Rybicki, Piękna Zosia: Pamięci Zofii Korbońskiej (Warszawa: Fundacja I’m. Stefana Korbońskiego w Warszawie, Oficyna Wydawnicza RYTM, 2011), p. 8.[/ref]

She was born Zofia Ristau on May 10, 1912, in Warsaw, Poland, finished the School of Political Science, and in 1938 married the great love of her life, Polish lawyer and political leader Stefan Korboński who during the Nazi occupation was the head of the Polish underground civilian administration. Zofia Korbońska’s main role during the war was to maintain coded radio communication with the Polish government-in-exile based in London.

Zofia Korbońska should be widely known for her contributions to liberty and the free press, but for reasons, I will explain later, she has been ignored by the Voice of America establishment. There are no radio or TV studios with a plaque bearing her name in the VOA building in Washington and no excellence in programming awards named after her at the U.S.-funded media outlet for foreign audiences, as there are for several of the men in VOA’s history. And yet, Zofia Korbońska is most likely the greatest World War II war hero and one of the best journalists who has ever worked there. Before and after she joined VOA, she contributed more to spreading freedom and democracy in the world than any of the men in the organization’s entire history. If it were not for Zofia and others like her, Europe might have never seen liberation from Nazi and Communist oppression.

One would think that Zofia Korbońska would be prominently mentioned in books about Voice of America and in VOA’s own promotional literature. VOA, however, has never been big on recognizing its women journalists. Almost all of VOA’s directors were men. One exception was Mary Bitterman who had served as VOA director during the Carter Administration. Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Amanda Bennett has just been named VOA director. A welcome change, but that’s not many women in the top position in 74 years. [As it turned out later, her tenure was marked by many management and programming scandals.] Most books about VOA’s history were written by men, with the notable exception of one of the more honest accounts of VOA’s early history by Holly Cowan Shulman, the daughter, and sister of VOA directors. Schulman’s book, The Voice of America: Propaganda and Democracy, 1941-1945, focused largely on VOA programs to Western Europe rather than Eastern Europe. Her research did not cover VOA broadcasts to Poland. Other books and recent statements from VOA officials present a revisionist history of the Voice of America designed to obscure the truth.

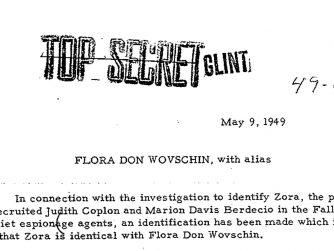

In connection with these attempts to re-write history and to prevent Americans, including current government officials and lawmakers, from learning from past mistakes, there is another, far more important reason why Zofia Korbońska and others like her have been left out of books and official VOA history accounts. Contrary to conventional wisdom and VOA’s own assertions that it helped bring down communism, which it did, VOA’s official establishment has never been particularly proud of some of VOA’s language services and their anti-communist war of ideas legacy. These higher-level officials preferred instead to stress VOA’s role as a purely journalistic outlet like CNN and its journalistic independence, which-ironically-they themselves helped to limit, at times significantly. Zofia Korbońska and others like her were an unwelcome reminder to them of the falsity of their narrative that VOA had started out as a news organization or that it functioned as a news organization throughout its history. The Voice of America was initially predominantly a propaganda operation dominated by left-leaning pro-Soviet sympathizers who slanted VOA programs in favor of the Kremlin, sometimes harming America’s image abroad, U.S. diplomacy, and military policy.

Zofia Korbońska was recruited after the war as a replacement for some of these pro-Soviet VOA broadcasters They chose to leave or were forced to leave during and shortly after the war, long before Senator McCarthy started chasing after communist ghosts who, with one or two exceptions, were no longer there. Most books about VOA history stress the excesses of McCarthy’s anti-communist witch-hunts, which affected VOA only marginally but say nothing about real communists and Soviet sympathizers who had worked for VOA during World War II. They say nothing about attempts to censor U.S. domestic media by VOA’s wartime parent agency, the Office of War Information, and certainly nothing about attempts by OWI officials to coordinate VOA propaganda with Soviet propaganda.

Even after she was hired by VOA in the late 1940s, as a woman and an anti-communist political refugee from Eastern Europe, Zofia Korbońska did not fully fit in with the all-male VOA establishment, especially since she was not afraid to speak out against poor journalism and attempts to falsify history. She herself was a model journalist, for whom the integrity of the news was sacred and the most important part of her job. From what I could tell, she enjoyed the most being a news editor and reporting news live. Some VOA managers, however, were willing to sacrifice the truth for political and other considerations. When they issued orders to censor news or to whitewash Soviet and communist history, they found a formidable opponent in Zofia Korbońska. She herself held liberal political views on many issues. She was appalled by racial discrimination and other social inequities in America, the country she loved as much as she loved Poland. But she was at the same time uncompromising on totalitarianism and communism. Far better educated and with considerably more journalistic experience than many VOA officials, she was admired by many but annoyed many others. When she died in 2010 in Washington at the age of 95, the Voice of America and its parent agency, the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG), failed to pay tribute to her remarkable life and achievements as a VOA writer, editor, and broadcaster.

I first wrote about Ravensbrück in my book, Wojtyla’s Women: How They Shaped the Life of Pope John Paul II and Changed the Catholic Church, when describing one of the most significant women in the pope’s life and his close friend, Polish psychiatrist Dr. Wanda Półtawska. She was a victim of Nazi medical experiments at the concentration camp where from 1939 to 1945, approximately 130,000 women from 40 different nations were held. Tens of thousands of them were murdered or died of hunger, illnesses, or medical experiments. After the war, Dr. Wanda Półtawska became one of Cardinal Karol Wojtyła’s assistants in trying to reduce the number of abortions through help centers for pregnant unmarried women and promoting Church-approved birth control education, which was one of the subjects of my book about Pope John Paul II and feminism.

The DW report by Sarah Hofmann “Forced abortions and medical experiments: Last survivors of Nazi women’s camp tell their horror stories” caught my attention because of my previous research on Polish women who fought Nazi and Communist totalitarianism. The DW program was not about Zofia Korbońska and did not mention her name, but it was about historical events in which she played a vital part.

Fortunately, Zofia Korbońska managed to avoid becoming a Nazi concentration camp prisoner. What she did was play a heroic role in helping to expose Hitler’s crimes against women. She avoided capture by the Nazis, but she and her husband were imprisoned for a while in Poland by the Soviet secret police NKVD in 1945. In 1947, they both escaped from Poland to avoid another arrest and most likely a death sentence. The Polish communist regime agents even made plans to kidnap and murder Stefan Korboński after the couple arrived in the United States. The plan had failed because one of the Korbońskis’ friends whom the agents tried to recruit to help them warned Stefan Korboński that his life was in danger.

The DW report was about several Polish survivors of Nazi medical experiments on women prisoners at the World War II Ravensbrück concentration camp, who had told their stories to British journalist-writer Sarah Helm decades after the war. Helm is the author of the book Ravensbruck: Life and Death in Hitler’s Concentration Camp for Women, and was interviewed by Deutsche Welle. DW reporter pointed out that Ravensbrück and the horrors of Nazi medical experiments on women at the camp are not as well known as what happened at Auschwitz, Dachau, Bergen-Belsen or Buchenwald. But the story of these medical experiments had gotten out first, thanks in large part to Zofia Korbońska, a future Voice of America broadcaster. In her book, Sarah Helm describes at some length the efforts of the Polish underground Home Army (Armia Krajowa) to smuggle out evidence of Nazi crimes from Ravensbrück and to make it available to journalists in Great Britain, the United States, and other free countries. While Zofia Korbońska is not named in Sarah Helm’s book, she was responsible for transmitting these Ravensbrück reports during the war from Warsaw to London.

Zofia Korbońska risked her life daily, gathering news and sending coded radio messages from Nazi-occupied Poland. They included news about the slaughter of Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto and efforts by the Polish underground to punish those who collaborated with the Germans. One of her husband’s many duties was to administer the underground court system, which passed death sentences on those who denounced Jews to the Germans. In an interview published in Poland in 2010 by Nasz Dziennik, Zofia Korbońska described her radio work:

Szyfrowałam lub rozszyfrowywałam wszystkie depesze poufne zarówno w jedną, jak i w drugą stronę. Dla przykładu depesze o miejscu kwatery Hitlera, depesza o V2. A także te, które były mniej tajne, jak np. depeszę dotyczącą likwidacji getta warszawskiego.

I coded and decoded all secret cables, those going out and those coming in. They included, for example, cables about the location of Hitler’s headquarters, a cable about the [German] V2 [rockets]. Also those which were less confidential, for example the cable about the [Nazi] liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto.

Zofia Korbońska’s coded radio messages describing some of these actions by the German occupiers or the Polish underground state and army were quickly transmitted back in news bulletins by shortwave signals from Great Britain by Radio Świt, the Polish word for “dawn,” which many Polish listeners wrongly assumed was based in Poland because it had the most up-to-date Polish news. Some of the same information coded by Zofia Korbońska was also used by the BBC, including reports from Ravensbrück about medical experiments on Jewish, Polish, and Russian women.

I wrote about Zofia Korbońska in an “Interweaving of Public Diplomacy and U.S. International Broadcasting” article in American Diplomacy, December 2011, and in “LIPIEN: Remembering a Polish-American patriot” in the Washington Times newspaper shortly after her death in 2010. If caught by the German Gestapo, who constantly searched for radio transmitters, Zofia Korbońska would have been tortured and executed – the fate of many of her colleagues in the Polish underground. She later fought in the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. Her courage was legendary.

In 1981, for his efforts to save Jews during the Nazi occupation of Poland, her husband, Stefan Korboński, received the “Righteous Among the Nations” medal from the Jewish Yad Vashem Holocaust Martyrs and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority in Jerusalem. Stefan Korboński was frequently interviewed by Radio Free Europe about his U.S. activities to promote freedom and democracy in Eastern Europe. He was a less frequent quest on VOA programs to Poland.

The Korbońskis were a wonderful couple, completely devoted to one another. Zofia would have probably been much happier and could have done much more as a journalist if she had chosen to work for Radio Free Europe in Munich, West Germany, but both she and Stefan had decided that they could do more for the liberation of Central and Eastern Europe from Soviet domination if they stayed in Washington.

Zofia Korbońska described her work at the Voice of America as “the continuation of the struggle in which she had engaged as a member of the Polish underground, this time waged from the West against the Soviet Union, the new occupying power in Poland.” She viewed VOA’s mission at that time as corresponding to what she and her husband wanted to work for: “the restoration of freedom and independence to the nations in Central and Eastern Europe under the Soviet domination.”

She received hundreds of letters and even presents from listeners in Poland. The letters were sent surreptitiously from Poland at some danger to those who sent them. The gifts included an effigy of the Soviet Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky, who on Stalin’s orders was put in charge of the Polish communist armed forces. In attacking Zofia Korbońska’s work at the Voice of America, a communist media commentator in Poland called her “a nightingale in a golden birdcage of American warmongers,” but she and other VOA Polish Service broadcasters had millions of faithful listeners.

She said that she was most proud of her news reports during critical historical moments: the Polish workers’ unrest in 1956, the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, and her live reporting after the assassination of President Kennedy, which she described as one of the most dramatic moments of her radio career.

When I worked with her at VOA in the 1970s and the early 1980s, I remember most vividly her constant frustration as a news editor with various attempts by American academics, journalists, and some U.S. government officials to whitewash history by promoting such ideas as convergence between Soviet Communism and Western democracy or the Sonnenfeldt Doctrine, which urged the Soviets and the Eastern Europeans to seek a more “organic” relationship. She would say that a few days in a Soviet prison might cure them of such silly and dangerous notions.

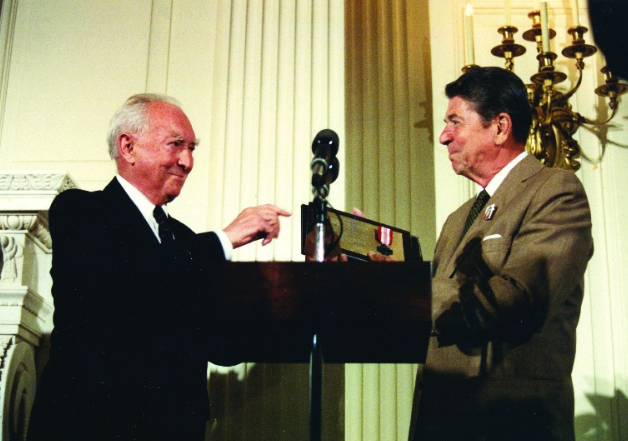

Zofia Korbońska rejoiced when Ronald Reagan was elected president. With her sharp sense of humor, she made fun of several USIA officials, still employed at the time at VOA in executive positions, who were horrified by some of President Reagan’s blunt statements about the Soviet Union. But despite many difficulties, she was very proud of her VOA career. In a 2001 interview, she described her work at the Voice of America as “a beautiful period in [her professional life]” and as “a contribution to the victory over the Evil Empire.”

A hero in her native Poland, Zofia Korbońska’s death in Washington at the age of 95 in 2010 was noted neither by the Voice of America nor the Broadcasting Board of Governors despite her decades-long career as a VOA editor, writer, and announcer. Zofia Korbońska’s friend, former National Security Advisor to President Carter, Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski, delivered in Polish a beautiful eulogy at her funeral.

“Miłość żąda ofiary” – te trzy słowa są dla mnie streszczeniem esencji życia Zofii Korbońskiej.

(…)

Zagranicą – praca trwała i ciężka, o niepodleglość i o wolność dla Polski – przez kilkadziesiąt lat – walka wymagająca poświęcenia i cierpliwosci oraz i głębokiej wiary – ale poświęcenie, cierpliwość, i wiara – to są cechy prawdziwie trwałej miłości.

Każdy kto znał Zofię Korbońską wie z jakim oddaniem, a jednoczesnie z osobistą skromnością i wybitną mądrością polityczną, ona tej wielkiej sprawie niezłomnie służyła – aż do samego końca.

Love demands sacrifice – these three words represent for me the essence of Zofia Korbońska’s life.(…)

Abroad — a constant and difficult work for independence and freedom for Poland — for several decades – a struggle which required sacrifice and patience, as well as deep faith – but sacrifice, patience, and faith – are what is true love.

Anybody who knew Zofia Korbońska knows with what great commitment, and at the same time with personal humility and outstanding political wisdom, she had served this great cause [Poland’s independence and freedom] without fail – to the very end of her life.

One of Zofia Korbońska’s major contributions to her adopted country was to save to some degree Voice of America’s reputation for telling the truth, a promise made in the first VOA radio broadcast in German but often not kept, especially before she joined VOA, but also at times in later years. When she and her husband defected to the West in 1947, former U.S. Ambassador to Poland Arthur Bliss Lane met them at the airport. He helped Zofia get a job at the Voice of America, where she used her experiences of resisting the Nazis and the Communists to try to change the content and the tone of VOA Polish programs. She had her own broadcasts: “Życie Warszawy pod komunizmem” (“Life in Warsaw under Communism”), „Klub myśli niezależnej – dyskusje młodzieżowe” (“Independent Thinkers Club – Teen Discussions”), “Traktorzystki i farmerki” (“Women Tractor Drivers and Farmers”), “Instytucje demokratyczne w Stanach Zjednoczonych” (“Democratic Institutions in the United States”).

Programs like these would not have been possible at VOA before she joined the U.S. broadcaster. Contrary to some books on VOA’s history, during World War II and shortly thereafter the station was not at all about giving both good and bad news without any censorship or propaganda. It was, in fact, a propaganda mouthpiece for the Roosevelt White House, and worse than that, it was a propaganda and disinformation mouthpiece for the Soviet Union thanks to many Soviet sympathizers working for the Voice of America at that time.

Zofia Korbońska tried to reverse this Soviet propaganda trend after the war. VOA’s official history, however, lionizes the first VOA director, Hollywood actor John Houseman, whose pro-Soviet sympathies and skewing of programs to make Stalin and the Soviet Union look democratic and to cover up communist crimes were too much even for the U.S. State Department. High-level State Department officials, who were not exactly anti-Soviet since Russia was still an important U.S. military ally against Hitler, had refused in 1943 to issue a U.S. passport to Houseman for official travel abroad. He resigned from his VOA position soon after that.

In his book, Defeat in Victory, published in the United States in 1947 by Doubleday, Jan Ciechanowski, former Ambassador of the Polish government-in-exile to Washington, correctly described Voice of America wartime broadcasts to Poland as “pro-Soviet propaganda.” While Zofia Korbońska was still in Poland practicing the most heroic type of journalism, Voice of America executives, journalists, and contributors were repeating Soviet TASS agency reports without any balance. Some were creating their own commentaries designed to cover up Stalin’s crimes, including the 1940 Katyn Forest massacre of thousands of Polish POW officers and intellectual leaders. At that time, even the U.S. State Department was appalled by this unrepentant pro-Soviet tilt and tried unsuccessfully to prevent VOA from directly supporting the Soviet Katyn lie. Contrary to conventional belief, the greatest enemies of journalistic freedom and practitioners of censorship at the Voice of America were, for the most part, not State Department or later the United States Information Agency diplomats, but VOA’s own managers and some journalists, because of their own political biases, fear, desire to maintain bureaucratic control, and very often simple ignorance.

“But, curiously enough, while some government departments realized the danger of unduly encouraging Soviet-Russian appeasement, some of the new war agencies actively conducted what could only be termed pro-Soviet propaganda,” wartime Polish ambassador to Washington Jan Ciechanowski wrote after the war.

“So-called American propaganda broadcasts to occupied Poland were outstanding proofs of this tendency. Notorious pro-Soviet propagandists and obscure foreign communists and fellow travelers were entrusted with these broadcasts.”

The most damning assessment of the Voice of America came from a radio journalist who worked in London during the war for the Polish-language radio station Świt, a surrogate British-supported broadcaster based in Britain but targeting Poland. He reported in a 1953 article in the Polish intellectual journal Kultura published in Paris of being horrified and depressed by the lack of news from Warsaw in Voice of America Polish programs in 1944 as Polish Home Army fighters were rounded up by the Nazis and the city burned. At that time, the Red Army stopped its fast-moving offensive and allowed the uprising to fail. Stalin hoped that the Germans would finish off anti-Communist Poles who might resist his takeover of Poland after the war.

Czesław Straszewicz described his impressions of VOA’s dismal WWII performance:

During the Warsaw Uprising, Świt could broadcast anything we wanted under the disapproving glances of the Brits.

With genuine horror, we listened to what the Polish language programs of the Voice of America (or whatever name they had then), in which in line with what [the Soviet news agency] TASS was communicating, the Warsaw Uprising was being completely ignored.

I remember as if it were today when the (Warsaw) Old Town fell [to the Nazis] and our spirits sank, the Voice of America was broadcasting to the allied nations describing for listeners in Poland in a happy tone how a woman named Magda from the village Ptysie made a fool of a Gestapo man named Mueller.

Unlike the Voice of America which was part of the mega propaganda agency in Washington, the Office of War Information (OWI), Świt and the BBC had much more independence and their British management showed much greater sophistication in dealing with sensitive news stories, such as the Warsaw Uprising or the 1940 Katyn massacre of more than 20,000 Polish military officers and other members of the Polish political and intellectual elite in the Soviet Union on Stalin’s orders.

The Office of War Information director, Elmer Davis, before the war a reporter and editorial writer for the New York Times and subsequently a popular CBS radio news presenter before being hired to run the OWI, where the Voice of America was placed, wrote a commentary for VOA and for distribution to U.S. domestic media in 1943 in which he unabashedly put the blame for the Katyn massacre on the Nazis, even though he was well aware of significant evidence of Soviet guilt.

One of the contributors to VOA programs Kathleen Harriman, a daughter of U.S. Ambassador to Moscow W. Averell Harriman, participated in a Soviet-arranged propaganda trip to Katyn for Western correspondents and wrote a report for the U.S. government accepting the false Soviet claim that the mass murder was committed by the Nazis. One VOA Polish commentator during World War II, Artur Salman who also used the pen name Stefan Arski, became after the war a chief anti-American propagandist in Poland. He was blasting the U.S. Congress for investigating the Soviet role in the Katyn massacre and his former employer, the Voice of America, for reporting on the investigation. Before he left the United States, Stefan Arski published a propaganda booklet for the communist government’s Embassy in Washington. Other wartime VOA Polish desk employees left when their spouses took jobs with the Polish communist government. The head of the VOA Czechoslovak desk during the war, Dr. Adolf Hofmeister, became Czechoslovakia’s ambassador to France after the communist regime took power in Prague with Soviet help.

After the departure of these and other pro-Soviet Voice of America broadcasters at the start of the Cold War and the hiring of Zofia Korbońska and other non-communist journalists, VOA programs to Poland had improved, but VOA was unable to overcome all censorship and restrictions on news reporting while it remained within the State Department and even in later years under the United States Information Agency. More accurate reporting on the Katyn massacre started at VOA in the early 1950s only under considerable pressure from U.S. public opinion and members of Congress and management and programming reforms carried out by the Truman administration. Radio Free Europe broadcasts became the primary source of uncensored news, information, and commentary for the Poles during the Cold War. RFE was not afraid to report on the Katyn massacre, while selective censorship of the story continued at VOA until the 1970s.

Zofia Korbońska did not suffer fools lightly and would not submit to censorship if she could help it. She fought for the truth, pointed out mistakes in Voice of America programs, and the VOA upper management disliked it. Despite her great talent, she was never promoted to be the director of the Polish Service. Her name is not mentioned in any history books written by former VOA officials. It’s not the kind of history that some former VOA personalities want Americans to remember.

VOA did experience a revival during the Reagan Administration and played a significant role as a news and information source as the Solidarity trade union struggled for democracy in Poland in the 1980s. VOA’s weekly audience in Poland skyrocketed from about 10% in the 1970s to over 50% in the late 1980s, with Solidarity’s secret polls showing even higher numbers. But one would not learn this from any book on VOA’s history. VOA’s audiences increased in almost every country in Eastern Europe in the 1980s, but according to several accounts by former VOA senior managers and central English newsroom correspondents, the Reagan years were allegedly the worst for journalism at the Voice of America. A few VOA reporters and BBG managers who either can’t identify Russian propaganda or still think that Putin’s official statements deserve equal time are now warning that “countering violent ISIL extremism” and seeking “impact” threatens VOA’s journalistic integrity. Most of them have very few followers on social media.

During the Cold War, VOA English broadcasts did much better. While most of the audiences were for VOA foreign language programs, VOA had a few English-speaking broadcasters who managed to connect with millions of radio listeners. Jazz expert Willis Conover and VOA Breakfast Show host Pat Gates (later a U.S. Ambassador) were both highly popular among VOA’s English-speaking radio audiences overseas. Radio Free Europe broadcasters were household names in Eastern Europe. Zofia Korbońska had millions of radio listeners in Poland. In 2006, she was awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta by Poland’s President.

Zofia Korbońska, a true hero of whom the Voice of America should be proud and who should not be forgotten, could tell some longtime VOA establishment officials, both past and present, what it means to be a VOA broadcaster, but I doubt that many of them would listen and understand. They would much rather forget this remarkable Polish American woman, a true hero, and remember John Houseman or even Elmer Davis, both of whom fell for Soviet propaganda, repeated it, and were very proud of their work.

Ironically, the Voice of America under its current independent agency, the Broadcasting Board of Governors [its name was changed in 2018 to the U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM)], is more similar to the Voice of America under its first independent agency, the World War II Office of War Information, than to the Voice of America under the State Department or the United States Information Agency — a later period when Zofia Korbońska was a VOA broadcaster. None of these structural arrangements was ideal, but VOA did much better when it was part of a larger U.S. government structure than when it operated within an independent agency subverted by Soviet agents of influence to promote Soviet Russia’s interests.

However, a connection to the U.S. government was not necessarily the case for all evil. The VOA Charter and the USIA link gave VOA both more independence and more effective oversight and stature, especially in later years. The worst enemy of the Voice of America has always been its internal bureaucracy and the bureaucracy of its sponsoring agency. Much of the censorship and poor journalism were often internally generated by VOA and USIA managers. Moreover, not infrequently, by VOA editors and reporters. Fortunately, VOA always had great journalists like Zofia Korbońska.

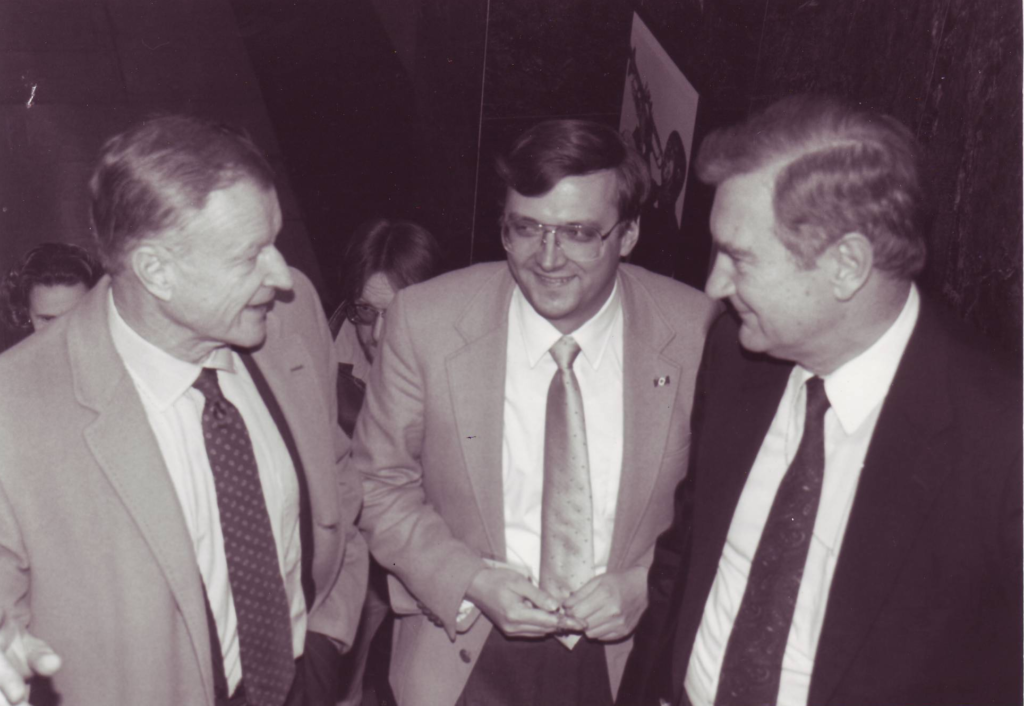

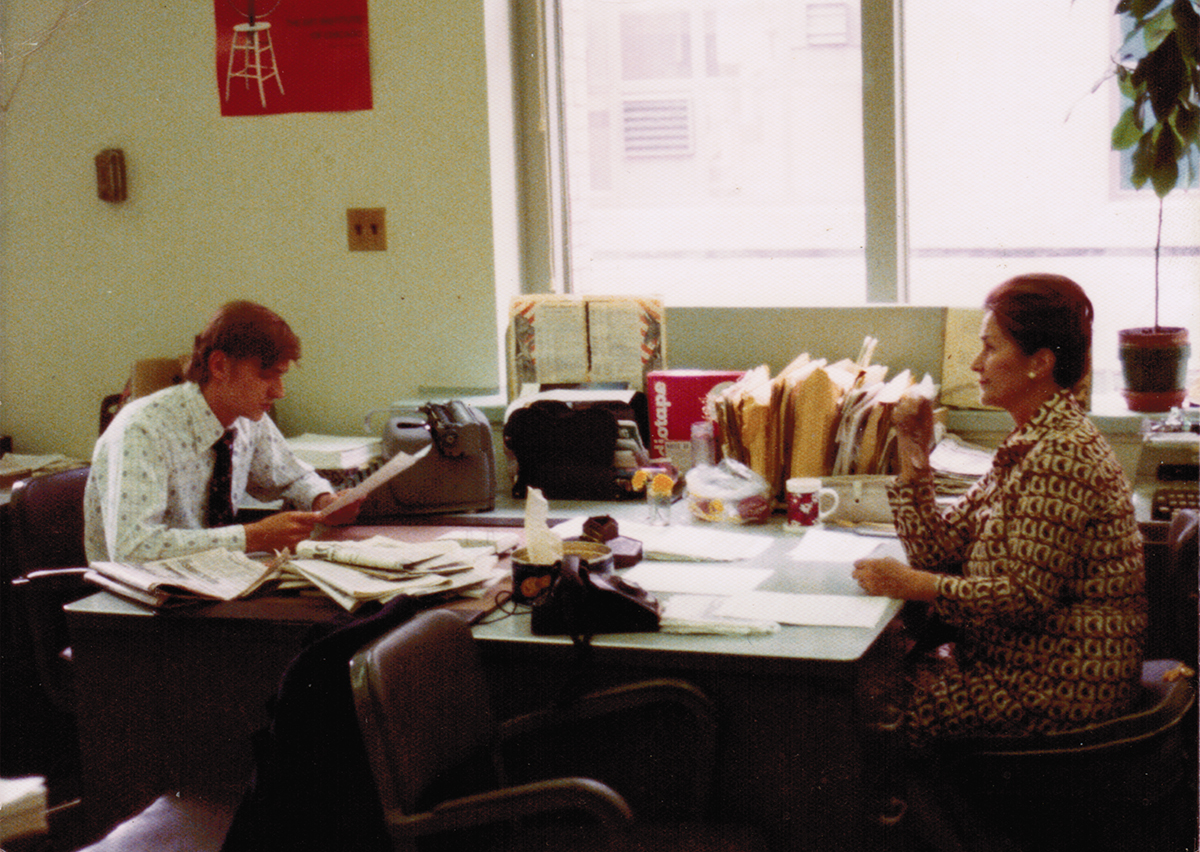

[Ted Lipien and Zofia Korbońska in the Polish Service office of the Voice of America, circa 1975. Fragment fotografii: Zofia Korbońska i Tadeusz Lipień w sekcji polskiej Głosu Ameryki w Waszyngtonie, 1974 r. Ze zbiorów prywatnych Tadeusza Lipienia, byłego szefa sekcji polskiej Głosu Ameryki.]

Informacja prasowa USAGM [U.S. Agency for Global Media – Agencji Stanów Zjednoczonych ds Globalnych Mediów]

USAGM uhonorowuje Zofię Korbońską, dziennikarkę sekcji polskiej Głosu Ameryki [Voice of America – VOA]

16 sierpnia 2020 r

Waszyngton, DC – Dziś mija 10-ta rocznica śmierci Zofii Korbońskiej, uczestniczki antyhitlerowskiego ruchu oporu w Polsce w czasie drugiej wojny światowej, która po wojnie w ucieczce przed sowieckim komunizmem wyemigrowała do Stanów Zjednoczonych jako uchodźca polityczny i przez wiele lat pracowała w sekcji polskiej Głosu Ameryki (VOA).

Urodzona w Warszawie w 1912 roku, Korbońska (z domu Ristau) była członkinią Armii Krajowej walczącej z hitlerowskim okupantem. Korbońska na co dzień ryzykowała życiem pod okupacją niemiecką pisząc i kodując tajne depesze radiowe do polskiego rządu na uchodźstwie w Londynie. Wiele jej depesz, które dotarły do wolnego świata, zostało nadanych z powrotem do okupowanej Europy przez BBC [również przez radiostację Świt]. Zawierały one informacje o mordowaniu polskiej inteligencji przez Gestapo, eksterminacji polskich Żydów, i eksperymentach medycznych na więźniarkach obozów koncentracyjnych.

Oprócz tajnej pracy radiowej, Korbońska była także partnerem w pracy swojego męża Stefana Korbońskiego, szefa Kierownictwa Walki Cywilnej i Delegata Rządu RP na Kraj. ( W 1980 r. Instytut Pamięci Męczenników i Bohaterów Holokaustu Jad Waszem przyznał mu tytuł Sprawiedliwego wśród Narodów Świata za ratowanie Żydów). Wkrótce po zakończeniu II wojny światowej Korbońscy zostali aresztowani w Polsce przez sowiecką tajną policję NKWD i zwolnieni po kilku długotrwałych przesłuchaniach. Obawiając się kolejnego aresztowania, w 1947 roku uciekli do Szwecji, ukrywając się na statku przewożącym węgiel.

Po uzyskaniu azylu w Stanach Zjednoczonych, Zofia Korbońska została zatrudniona przez Głos Ameryki w 1948 roku z rekomendacji byłego ambasadora USA w Polsce Arthura Bliss Lane. Korbońska pracowała najpierw w Nowym Jorku, a później w Waszyngtonie, używając pseudonimu Zofia Orłowska, aby ochronić swoją rodzinę i przyjaciół w Polsce przed represjami. Nawet po przejściu na emeryturę po ponad trzydziestu latach pracy, Korbońska nadal pisała i nagrywała audycje dla rozgłośni w latach 80 tych.

W 2006 roku Korbońska otrzymała tytuł honorowego obywatela miasta stołecznego Warszawy. Prezydenta RP [Lech Kaczyński] przyznał jej jedną z najbardziej prestiżowych odznaczeń cywilnych w Polsce [Krzyż Wielki Orderu Odrodzenia Polski.] Zofia Korbońska zmarła w Waszyngtonie 16 sierpnia 2010 roku. W przemówieniu na jej pogrzebie, Dr Zbigniew Brzeziński, były doradca prezydenta Jimmy’ego Cartera ds. bezpieczeństwa narodowego, stwierdził: „Zofia Korbońska – bohatersko odważna w walce, rozważna na politycznej emigracji – była przykładem na czym polega oddana i udana służba w wielkiej sprawie. ”

Agencja Stanów Zjednoczonych ds. Globalnych Mediów i Głos Ameryki będą zawsze z wdzięcznością pamiętać o Zofii Korbońskiej i wszystkich dziennikarzach Głosu, dawnych i obecnych, którzy pracowali i pracują na rzecz wolności i demokracji.