Revealed U.S. Government Officials Identified to Him As Soviet Agents

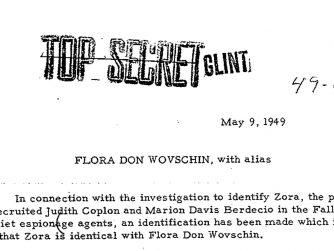

On July 31, 1951, Alexander Barmine, the former Brigadier General of the Soviet Army’s military intelligence and the then chief of the Voice of America Russian Branch (from about 1948 until 1964), made a stunning revelation while testifying under oath before the United States Senate’s Special Subcommittee to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws, 1951–77, known more commonly as the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee (SISS) and sometimes the McCarran Committee after its chairman, Senator Patrick Anthony McCarran (Democrat – Nevada). Barmine, who after his defection in 1937 from the Soviet Embassy in Athens was sentenced to death in absentia in the Soviet Union, told the subcommittee that his boss in the Soviet military intelligence, General Yan Karlovich Berzin, identified to him two Americans as “our men,” which meant that they were Soviet agents. Berzin, a Latvian Soviet communist, was shot during Stalin’s Great Purge of 1938.

According to Barmine, Joseph Fels Barnes and Owen Lattimore were the two men. From 1932 to 1934, Barnes was a reporter for the New York Herald Tribune based in Moscow and Berlin. They both vehemently denied they were Soviet agents. The information made public by Barmine could not be corroborated with documentary evidence, although several other witnesses testifying before congressional committees claimed Barnes and Lattimore had been either Soviet sympathizers or Communist Party members. They denied these claims as lies. A few other witnesses also expressed doubts that they could have belonged to the Communist Party or were communist sympathizers. During World War II, Lattimore and Barnes served in high-level positions in the Office of War Information (OWI). Joseph Barnes was one of the founders of the Voice of America, which was part of the OWI’s wartime propaganda operations at that time.

Barnes and his boss, Robert E. Sherwood, who was also President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s speechwriter and was in charge of coordinating U.S. and Soviet propaganda at OWI before resigning to work for FDR’s reelection in 1944, were, in fact, the Voice of America’s first directors. They were in charge of determining VOA program content.1 In contrast, John Houseman, who has been presented for decades as the first VOA director, was only responsible for radio production. Houseman was not a journalist but a theatre producer and pioneer in fake entertainment radio news.2 He and Barnes were forced to resign by the otherwise very pro-Soviet Roosevelt administration, but not over charges of spying for Russia. Both were secretly identified to the Roosevelt White House in April 1943 by Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles as being excessively pro-Soviet, long before Alexander Barmine said anything to the FBI or the McCarran subcommittee. An addendum to the April 6, 1943 memorandum from Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles to Marvin H. McIntyre, Secretary to President Roosevelt, said about Joseph Barnes:

It is reliably stated that there has been no crucial point in Russian development, since 1934, when Barnes has not followed the Party line and has not been much more successful than the official spokesman in giving it a form congenial to the American way of expression.3

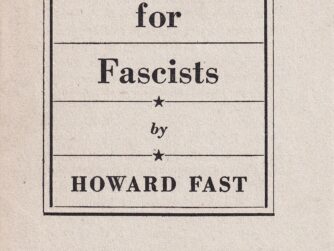

The State Department accused Houseman of hiring communists for VOA jobs and refused to provide him with a U.S. passport for government travel, thus forcing his resignation in mid-1943. The only far-fetched claim in the State Department memo supporting the accusations against Houseman was that Native Son, a book by an African American writer Richard Wright, which Houseman co-produced as a play before he started working for the U.S. government, was somehow “possibly subversive in intent and un-American.” Wright’s book was not subversive, but Houseman’s theatrical production of it may have whitewashed the violent nature of Communism, which Wright himself was not afraid to show in his book. As his conflicts with the party leadership intensified, two white Communists beat him up at a May Day march in Chicago in 1936. After he announced his intention to leave the Communist Party, Communists called Richard Wright “a traitor.” He eventually made a complete break with the Communist Party and published an anti-communist essay in the 1949 book The God That Failed.

Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, who in 1943 had identified Joseph Barnes and John Houseman to the Roosevelt White House as possible security risks because of their excessive pro-Soviet sympathies, was hardly a right-winger. He was President Roosevelt’s close friend and advisor, who preferred him to his Secretary of State Cordell Hull. To Roosevelt’s disappointment, Welles had to resign later in 1943 when accusations of a disputed homosexual incident were reported. In his April 1943 memorandum to the White House, Welles did not oppose hiring liberals to be in charge of the U.S. government’s information programs. He objected, however, to hiring Soviet sympathizers with possible links to communist parties and possible divided loyalties that made them vulnerable to manipulation because of their naive view of communism and Soviet Russia.

If it is desired to give a distinctly liberal cast to these organisations, it would seem possible to find men who are liberal in the light of their own conviction, and of the American ideal, rather than men who have, for one reason or another, elected to give expression to their liberalism primarily by joining Communist front organizations, and apparently sacrificing their independence of thought and action to the direction of a distinctly European movement.4

Joseph Barnes and some of his associates were forced to resign a few months after Houseman departed from VOA in mid-1943. Following the communist and Soviet propaganda line, Voice of America broadcasters working under Barnes called the King of Italy “a moronic little king” when General Eisenhower tried to ensure Italy would break its alliance with Nazi Germany. The scandal involving Joseph Barnes and his deputies at the Voice of America became public on July 28, 1943, when the New York Times published a front-page story by its Washington correspondent and bureau chief Arthur Krock with the headline: “President Rebukes OWI for Broadcast on Regime in Italy.” Krock wrote that VOA was reflecting the ideological preferences of Moscow, Communists, and fellow travelers:

The selections of opinions made by the OWI were drawn heavily from purely personal journalistic sources––otherwise undistinguished––which have opposed the President’s Vichy and North African policies and usually produce an “ideology” that conforms much more closely to the Moscow than to the Washington-London line.

The explanation [from OWI officials] also failed to deal with the high official view here that the New York shortwave department of the OWI [Voice of America] deliberately and constantly borrows from these sources to discredit the authorized foreign policy of the United States Government, or to reshape it according to the personal and ideological preferences of Communists and their fellow-travelers in this country.5

Eisenhower later called the VOA broadcast an act of “insubordination” toward President Roosevelt.6 However, there were no public charges of spying for Russia made against Joseph Barnes, neither during World War II nor later, until Alexander Barmine testified before the McCarran Subcommittee in 1951.

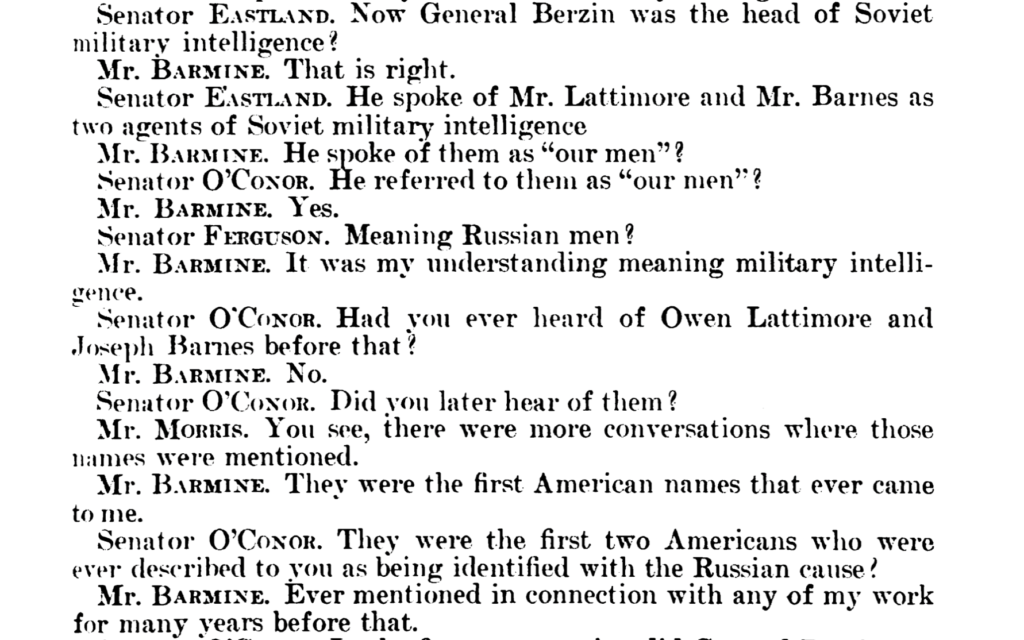

Senator EASTLAND [James O. Eastland Democrat – Mississippi]. Now General Berzin was the head of Soviet military intelligence?

Mr. BARMINE. That is right.

Senator EASTLAND. He spoke of Mr. Lattimore and Mr. Barnes as two agents of Soviet military intelligence?

Mr. BARMINE. He spoke of them as “our men.”

Senator O’CONOR [Herbert R. O'Conor Democrat – Maryland]. He referred to them as “our men”?

Mr. BARMINE. Yes.

Senator FERGUSON [Homer Ferguson Republican – Michigan]. Meaning Russian men?

Mr. BARMINE. It was my understanding meaning military intelligence.

Senator O'CONOR. Had you ever heard of Owen Lattimore and Joseph Barnes before that?

Mr. BARMINE. No.

Senator O’CONOR. Did you later hear of them?

Mr. MORRIS [Robert Morris, Special Counsel]. You see, there were more conversations where those names were mentioned.

Mr. BARMINE. They were the first American names that ever came to me.

Senator O’CONOR. They were the first two Americans who were ever described to you as being identified with the Russian cause?

Mr. BARMINE. Ever mentioned in connection with any of my work for many years before that.7

Not surprisingly, Joseph Barnes and Owen Lattimore immediately denied any role in spying for the Soviet Union or connections to the Communist Party. Barnes, the former high-ranking official in the Office of War Information responsible for Voice of America broadcasts and former foreign correspondent, stated through his office at Simon & Schuster, where he worked as an editor:

I have never in my life seen Alexander Barmine or General Birzin [sic], both of whom seem to be specialists in the kind of unmitigated lying professionally engaged in by both Communists and ex-Communists.

In 1934 I made a survey of Russian research in the Pacific area for the Institute of Pacific Relations and met some of the scholars in this field. In 1937 and 1938 I was the Moscow correspondent of The New York Herald Tribune. During this time I covered the great purge, and was threatened with expulsion for the details of Soviet treachery and corruption which I reported.

Having been cleared by all the investigative agencies of the United States for work in the Office of War Information and later for accreditation as a war correspondent, I am glad to repeat that I have never been a Communist, a sympathizer with communism, an agent for the Soviet Union or a willing participant in the kind of political warfare through personal denunciation in which Communists and ex-Communists and ambitious politicians are now engaged.8

Prof. Owen Lattimore described Alexander Barmine’s testimony before the Senate’s subcommittee chaired by Senator McCarran as “one of the flimsiest yarns I have ever heard.”9 He added that Barmine “had bobbled the play” in his statements. Lattimore insisted:

Of course, I have never been connected with Soviet Military Intelligence in any way, shape or form, in any year A. D. or B. C. But it is a particularly comic blunder to make out that I was a hanger-on of the Russians in the period 1933-35. At that time I was completing ten years of exploration and study in Sinkiang, Mongolia and Manchuria. I had never been in Russia. In 1927, when I was exploring in Sinkiang, the Russians prevented me from entering their territory."10

About Barmine’s testimony that he had been dismissed from the Office of Strategic Services, the U.S. government’s World War II intelligence agency, “for repeated absence from duty because of sickness,” Owen Lattimore, who was then the head of the Walter Hines Page School of International Relations at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, said that “it sounds like a case of psychological instability marked by chronic hallucinations.”11 Barmine also said, however, that the real reason for his dismissal from the OSS was the publication of his Reader’s Digest article, in which he warned against the Soviet influence operations within the U.S. government.

In 1941, President Roosevelt appointed Lattimore, who advocated for a stronger Soviet role in China, to serve as U.S. advisor to Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek, a position he held for one and a half years. The 1943 Official Register of the United States listing persons occupying administrative and supervisory positions in the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of the Federal Government and in the District of Columbia Government, as of May 1, 1943, showed Owen Lattimore as Pacific Bureau Director at the Office of War Information San Francisco Regional Office, and thus responsible for Voice of America broadcasts to Asia, including China. In 1944, Lattimore was named OWI deputy director in Washington in charge of all Pacific programs but resigned at the end of the year to return to Johns Hopkins University.

NOTES:

- Ted Lipien, “75th Anniversary of Voice of America – Propaganda Coordination with USSR – Cold War Radio Museum,” accessed April 19, 2023, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/75th-anniversary-of-voice-of-america-propaganda-coordination-with-ussr/.

- Curator, “Future First Voice of America Director Introduces Americans To Entertainment Fake Radio News in 1938 – Cold War Radio Museum,” accessed November 2, 2022, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/timeline/future-first-voice-of-america-director-introduces-america-to-fake-entertainment-radio-news-in-1938/.

- State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944, From Collection: FDR-FDRPSF Departmental Correspondence, Series: Departmental Correspondence, 1933 – 1945 Collection: President’s Secretary’s File (Franklin D. Roosevelt Administration), 1933 – 1945, National Archives Identifier: 16619284.

- Ibid.

- Arthur Krock, President Rebukes OWI For Broadcast On Regime In Italy, Personal Attack on King and Fascist Label for Badoglio Strongly Denounced, The New York Times, July 28, 1943, pp. 1 and 5.

- Dwight D. Eisenhower, The White House Years: Waging Peace 1956-1961 (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, 1965), p. 279.

- United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on the Judiciary. Subcommittee to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws., United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on the Judiciary. Subcommittee Investigating the Institute of Pacific Relations. Institute of Pacific Relations.: Hearings before the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee To Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws, Subcommittee Investigating the Institute of Pacific Relations, Eighty-Second Congress, First Session, Eighty-Second Congress, Second Session. Washington: U.S. G.P.O., p. 201, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d02120505q.

- William S. White, "Lattimore and Barnes Linked to Soviet Spies But Deny It," The New York Times, July 31, 1953, p. 1, and p. 7, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1951/08/01/88438625.html?pageNumber=1.

- The New York Times, “Lattimore Assails ‘Flimsiest Yarn’,” August 2, 1951, p. 4, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1951/08/02/88440253.html?pageNumber=4.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.