Supported Truman Reforms at VOA

Alexander Barmine is credited with changing the program of the VOA Russian branch from being neutral on communism and the Soviet leadership under his predecessor as branch chief and later VOA director Charles Thayer, who hired Barmine, to counter the Soviet propaganda. Early VOA Russian broadcasters working under Thayer were not allowed to criticize the Soviet Union, as one of them, Helen Zhemchuzhny Bates Yakobson (1913-2002), noted in her memoir published in 1994.

In those early years, VOA programs attempted to give full and impartial reports of life in the United States, including confessions of our shortcomings and faults. No direct criticism or attacks on the Soviet system were permitted. After all, they had only recently been our allies. But as the Cold War intensified, VOA responded and became openly and vigorously critical of the Soviet system and government.1

Barmine did not say anything negative about Thayer while testifying, even though he had to know that McCarthy suspected Thayer of being a Soviet sympathizer. According to Helen Jakobson, Thayer was a “talented writer with a touch of whimsy” who understood the power of “radio diplomacy” in combating Soviet propaganda but also knew that Americans had “moral aversion” to propaganda in U.S. broadcasting. She believed that Thayer saw VOA’s mission as “the battle for men’s minds,” but she admitted that strong criticism of the Soviet Union was not permitted while he was in charge of the Russian broadcasts at their launch in 1947.2

Charles Thayer wrote in one of his books that to help with the first VOA Russian broadcasts, he had hired Kathleen Harriman to work as a volunteer.3 She was the daughter of W. Averell Harriman, President Roosevelt’s ambassador to the Soviet Union. She did volunteer reporting for the Office of War Information from London and Moscow during the war with Germany. In January 1944, her father sent her on an NKVD-arranged trip to Katyn, after which she wrote a confidential report for the State Department supporting the Soviet propaganda lies about the massacre. She admitted later, while testifying before the Madden Committee on November 12, 1952, that the Soviets deceived her.4

Victor Franzusoff presented a largely sympathetic picture of Charles Thayer’s role at the Voice of America Russian Service. According to Franzusoff, Thayer was pleased with his interview with the movie actor Adolph Menjou, who went into an anti-Soviet and anti-communist tirade. Still, such criticism appeared to have been rare in VOA programs to Russia before Alexander Barmine became the Russian Service chief.5 Charles Thayer was forced to resign from the Foreign Service under pressure from Senator McCarthy over sexual affairs, apparently to help win Senate confirmation of his brother-in-law, Charles Bohlen, as Ambassador to Russia. In 1959, Charles Thayer accompanied former Ambassador Harriman on a reporting trip to the Soviet Union. By then, both men were no longer working for the State Department.

When the Russian broadcast was first started, an AP report said, “all staff members are reported to have been carefully screened to eliminate any with either Communist or anti-Soviet feelings.”6 The AP report suggested that Assistant Secretary of State William Benton closely supervised the selection of the Voice of America’s Russian Service’s initial staff to ensure that neither Communists nor anyone highly critical of the Soviet Union would be hired. It was not entirely true that there were no anti-Communists in the first group of VOA Russian broadcasters. One of them was Nicolas Nabokov, a former professor of philosophy at St. John’s College in Maryland. A first cousin of Russian-American writer Vladimir Nabokov of Lolita fame, he was undoubtedly anti-Soviet and anti-communist, as were many other VOA Russian Service broadcasters. Still, in 1947, they were not allowed to criticize Stalin or the Soviet system.

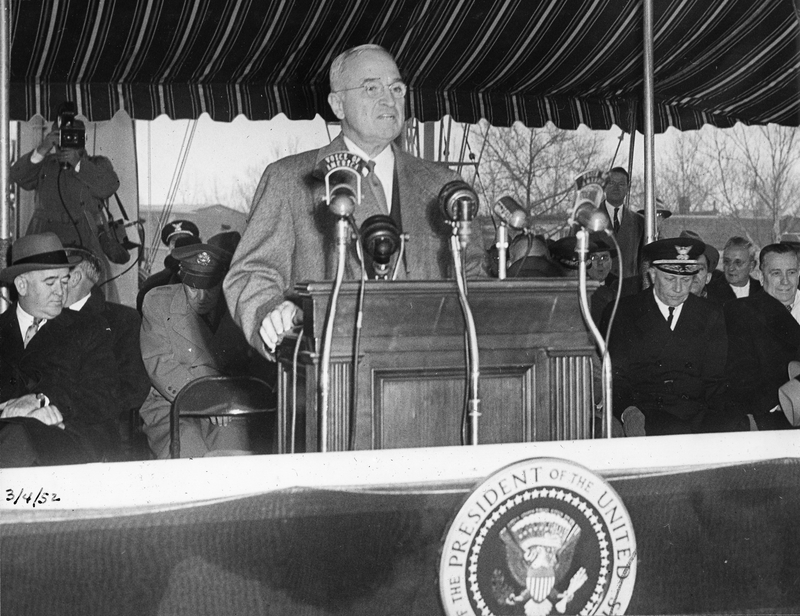

The push for change came from members of Congress of both parties, U.S. media, and President Truman, but Barmine was directly responsible for implementing significant reforms in VOA’s Russian Branch. President Harry Truman unveiled the “Campaign of Truth”– a multi-faceted U.S. government’s international information policy – in a foreign policy speech on April 20, 1950, to members of the American Society of Newspaper Editors as the answer to harsh Soviet propaganda attacks on the United States and its allies.7 He was also responding to domestic criticism that his administration was not doing enough to counter disinformation from the Soviet Union and other communist regimes. Truman’s “Campaign of Truth” address was designed to inspire journalists, including Voice of America’s federal employees of the Department of State broadcasting at the time to the world in multiple languages from the VOA studios in New York, to offer more robust and more effective resistance to Soviet propaganda and communist influence. “Everywhere that the propaganda of the Communist totalitarianism is spread, we must meet it and overcome it with honest information about freedom and democracy,” Truman said. He also alluded to the media’s criticism of his foreign policy and indirectly to criticism of the Voice of America. “Foreign policy is not a matter for partisan presentation,” Truman said as he outlined his administration’s plan to resist communism and its propaganda with the “Campaign of Truth.”

NOTES:

- Helen Yakobson, Crossing Borders: From Revolutionary Russia to China to America (Tenafly, N.J: Hermitage Publishers, 1994), p. 146.

- Ibid. pp. 45-46.

- Charles W. Thayer, Diplomat (London: Michael Joseph, 1959), p. 187.

- Ted Lipien, “Voice of America Freelancer Who Promoted Stalin’s Propaganda Lie on Katyn Massacre – Cold War Radio Museum,” April 25, 2023, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/voice-of-america-freelancer-who-promoted-stalins-propaganda-lie-on-katyn-massacre/.

- Victor Franzusoff, Talking to the Russians: Glimpses of History by a Voice of America Pioneer (Santa Barbara, Calif: Fithian Press, 1998), p. 107.

- AP report in The Mobile Press Register, “U.S. to Start Radio Programs Aimed at Reds: State Department Directs News, Music, Features to Inform the Russians,” February 2, 1947, p. 1.

- Harry S. Truman, “Address on Foreign Policy at a Luncheon of the American Society of Newspaper Editors,” April 20, 1950. National Archives, Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/library/public-papers/92/address-foreign-policy-luncheon-american-society-newspaper-editors.