By Ted Lipien

A partial answer to the question of why the Voice of America (VOA) and the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) had no Russian-language radio broadcasts to the Soviet Union until after the end of World War II can be found in the biography of William Benton by Sidney Hyman. William Benton (1900–1973) was a United States Senator (D) from Connecticut (1949–1953), publisher of the Encyclopædia Britannica (1943–1973), and Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs from August 31, 1945 to September 30, 1947.

In his role as U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs, Benton was in charge of Voice of America broadcasts, which were then produced under the supervision of the State Department. He traveled to Europe in the fall of 1945 and met in London with William Haley (later Sir William), the head of BBC.

Hyman wrote in The Lives of William Benton that during their meeting in London in 1945, Benton asked Haley why the British were not broadcasting to the Soviet Union in Russian. At that time, the Voice of America also did not have Russian-language or Ukrainian-language radio programs.

It would be surprising that Benton truly did not know the answer to his question. Both during and immediately after the end of World War II, U.S. officials in charge of VOA, many of them strongly pro-Soviet, did not want to do anything that might have offended Stalin. The head of BBC probably told Benton what he already knew.

“The Russians broadcast to us in English, and also to you, said Haley dryly. “They say they want to cooperate with us on our kind of democracy–which favors freedom of speech and freedom of information. They ask us to reciprocate by cooperating with them on their kind of democracy. In their kind, they do not believe in freedom of speech and do not want us to broadcast to them.1

Sir William Haley would later become the editor of the London Times. At Benton’s request, Haley was also editor-in-chief of Encyclopædia Britannica from January 1968 until resigning in an editorial dispute in April 1969.

Hyman’s book presents Benton as “Creator of ‘The Voice of America’.” It is true that Benton may have been the first higher-ranking U.S. government figure who officially used the “Voice of America” name to describe U.S. government radio broadcasts. They were first launched during World War II not as the Voice of America but under various other names. In 1945, President Truman put the U.S. government broadcasting under the control of the State Department when he abolished the Office of War Information (OWI), where it had been since 1942. But while Benton popularized the Voice of America name shortly after the war, he could hardly be called the creator of VOA broadcasts. His main achievement was to convince Congress to approve money for U.S. public diplomacy programs abroad through the 1948 Smith-Mundt Act. He could, however, claim some credit for starting the Voice of America broadcasts in Russian, even though they turned out to be too accommodating toward a repressive regime and were later made more hard-hitting by other Truman administration officials. The note about the author on the jacket of his 1958 book, This Is The Challenge: The Benton Reports of 1956-1958 On The Nature Of The Soviet Threat, says, “He launched the first Voice of America broadcasts in the Russian language.”2 His essays, on the whole, present a largely naive view of the Soviet Union based on his visit there in 1955 and his talks with communist officials. They reflected his conviction that dialogue with them would drastically transform their thinking and the Soviet system. This was also his hope for launching VOA broadcasts in Russian in 1947.

William Benton did not create VOA, although his belief in the convergence of communism and democratic capitalism through academic and other exchanges, U.S. public diplomacy, and VOA broadcasting was never entirely abandoned by VOA’s senior management until the first year of the Reagan administration. These public diplomacy efforts did have some positive influence outside of the Voice of America – more in East-Central Europe than in the Soviet Union. But through the management and programming influence of the U.S. Information Agency (USIA) over the Voice of America, USIA’s and the State Department’s public diplomacy also led to the censorship of some of the criticism of the Soviet Union and its satellite regimes and undermined the potential effectiveness of VOA and its broadcasts.

Such censorship was successfully resisted at Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty, but some U.S. diplomats tried to get RFE and RL programs censored. U.S. Ambassador to Poland Jacob Beam made an unsuccessful attempt to shut down RFE’s Polish Service.3 Polish communist intelligence service and secret police spied on Voice of America’s jazz expert Willis Conover during his visit to Poland in 1959 and tried to exploit it to influence U.S. diplomats into silencing Polish broadcasts of Radio Free Europe. They were helped in targeting U.S. diplomats by a former World War II writer and editor of VOA broadcasts, Mira Złotowska Michałowska, who returned to Poland after the war and married a high-ranking communist diplomat.4 As a journalist and writer, she also produced soft propaganda for the regime.

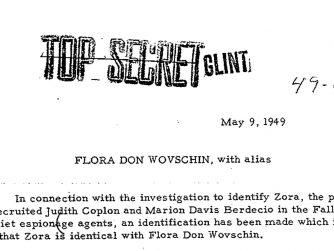

William Benton’s approach in launching the first VOA Russian-language radio program was to foster better understanding and build bridges between the United States and communist-ruled nations, including their regimes and their officials. But U.S. public diplomacy could not make these undemocratic and illegitimate regimes democratic and legitimate in the eyes of the oppressed populations. While Benton was not the first to try to popularize the Voice of America name for U.S.-government-produced radio broadcasts for overseas audiences, he set the tone for VOA journalism of limited criticism of the Soviet Union and its satellites. In one of many ironies in VOA’s history, the first time the Voice of America name appeared in print may have been in a socialist pamphlet published in the United States in 1943 by OWI employees who helped to create some of the first wartime radio programs. A few of the OWI journalists who promoted the VOA name in a socialist publication were in contact with known Soviet spies and agents of influence during the war. After the war, some of them worked for Stalinist regimes in Eastern Europe as anti-U.S. propagandists.5

World War II Voice of America broadcasts, which only officially acquired that name after the war, were produced in the Office of War Information, which was created by President Roosevelt in 1942 through an executive order. The hiring of Soviet sympathizers by OWI was soon discovered and criticized in the U.S. Congress, which during the war, defunded OWI’s domestic propaganda programs and reduced the budget for overseas radio broadcasts but did not eliminate them.

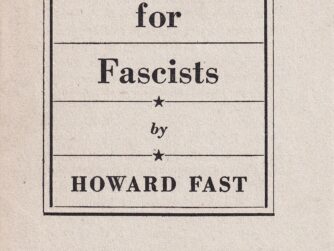

As the Office of War Information became a target of congressional and media criticism, John Houseman, the chief producer of the first radio broadcasts, was quietly forced to resign by the Roosevelt administration in 1943 for hiring Communists for VOA jobs.6 Later references to Houseman as the first Voice of America director are not entirely accurate since he was mainly in charge of radio production rather than being responsible for program content, but his protégé, Howard Fast, was selected in 1942 as the first VOA chief news writer and editor. Fast was forced to resign two years later, but many pro-Soviet fellow travelers and communist sympathizers remained on the government payroll as VOA officials, managers, editors, and broadcasters. Some were not replaced until several years after the war. The first VOA news chief, Howard Fast, was a successful writer of historical novels, a Communist Party activist, and a journalist for the Party’s newspaper, the Daily Worker. In 1953, Fast received the Stalin International Peace Prize.7

Former Communists who became opponents of Soviet communism helped to expose Soviet influence within the Voice of America already in the late 1940s, several years before Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-WI) started making his largely unsubstantiated accusations and looking for Communists in the U.S. government who had already been fired or left their jobs under pressure from the Truman administration. After his break with communism, Oliver Carlson, an American writer, journalist, founder of the Young Communist League of America, and lecturer at the University of Chicago, wrote in 1947 about the Office of War Information as the U.S. government’s tool for spreading pro-Soviet propaganda and disinformation:

During the War Years — and largely with government blessing — the Communists moved en masse on the radio, as they did on the movies and the press to help “sell” the American people on the virtues of our Soviet ally. The idea officially projected through such organizations as the O.W.I., was to cure “misunderstanding” of Soviet Russia, which was suddenly discovered to be a “democracy” and a noble social experiment. […] Tens of millions of radio listeners were deluged with streamlined and dramatic presentations to prove that any talk of Russia as a ruthless dictatorship was a “reactionary” plot. The Bolshevik regime, it turned out, was just a Russian version of our own War for Independence, Lenin a Russian replica of George Washington, Stalin a compendium of Jefferson, Jackson and Lincoln.8

Carlson’s descriptions of pro-Soviet propaganda by the OWI were similar to Julius Epstein’s observations, who wrote after the war that the wartime Voice of America promoted “Love for Stalin.”9 Epstein, a Jewish refugee born in Austria, worked for OWI during the war on the German desk. He was briefly a Communist Party member during his student years in Germany but quickly became a critic of communism. Before emigrating to the United States, he was an internationally-published journalist in Europe. In 1950, Epstein was writing about pro-Stalin Communists working for the Office of War Information during the war. Congressman George A. Dondero (R-MI) quoted Epstein in the Congressional Record on August 9, 1950. The quote was from an article that appeared in the Evening Star Washington newspaper on August 7, 1950.

There are still too many of the old OWI [Office of War Information] employees working for the Voice, both in this country and overseas. I mean those writers, translators and broadcasters who so wholeheartedly and enthusiastically tried for many years to create “love for Stalin,” when this was the official policy of our ill-advised wartime Government and of our military government in Germany. There is no doubt that all those employees were at that time deeply convinced of the absolute correctness of that pro-Stalinist propaganda. How can we expect them to do the exact opposite now?”10

Epstein also wrote in 1950:

When I, in 1942, entered the services of what was then the “Coordinator of Information,” which became after a few months the O.W.I., I was immediately struck by the fact that the German desk was almost completely seized by extreme left-wingers who indulged in a purely and exaggerated pro-Stalinist propaganda.11

It would take U.S. government officials in the State Department several years before they even considered starting Voice of America radio broadcasts in Russian. Sidney Hyman, William Benton’s biographer, wrote that in 1945 Benton “had not decided on direct broadcasts [in Russian] to the Soviet Union” when he became the Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs.

According to Hyman, at the end of 1945, “no one even thought of such broadcasts.”12 If that were the case, it showed the incredible strength of Soviet propaganda influence within the U.S. government and the irrational fear of offending Soviet leaders.

In 1946, Benton said that the question of whether to start VOA Russian-language broadcasts was already under consideration, but the final decision had not yet been made. After his meetings in London, Benton had the idea of starting Voice of America broadcasts in Russian using the powerful radio transmitters in Munich, which were then under the control of General Lucius D. Clay, military governor of the United States Zone, Germany, from 1947 to 1949.13 According to Benton’s biographer, General Clay refused to give up the unused Munich transmitters and had to be ordered by the Secretary of War Robert Patterson to turn them over to Benton to begin the Voice of America Russian broadcasts.14

Benton thought General Clay did not want to use the Munich radio transmitters and another transmitter in Berlin “because the Russians didn’t like it.” As U.S. deputy military governor and later governor in post-war Germany, Clay tried at first to stick to the wartime agreements with the Soviet Union regarding the occupation of the country, including the management of radio broadcasts and other media, but he soon realized that the Russians were not keeping their promises. In 1948, he initiated the Berlin Airlift after the Soviets imposed their blockade of the city. Clay opted for allowing the Germans to develop their own media and, for some surrogate local radio broadcasting, initially under the control of the U.S. military in Germany. He resisted efforts of the Office of War Information and later the State Department bureaucracy in Washington to play a significant media role in Germany, but he did have limited praise for the Voice of America as a provider of news from the United States in cooperation with the U.S. Army.

Meanwhile the Department of the Army had organized a news service in New York, in close cooperation with the State Department, to supply material on United States international policies and information for both periodicals and radio. The Voice of America, and particularly its excellent news reviews for radio, added to this program.15

Clay understood that Voice of America broadcasts had some usefulness but could make up for bad U.S. policy decisions. When Senator J. William Fulbright (D-AR) introduced legislation to keep in the United States an art collection taken from Germany for safekeeping, General Clay opposed the bill and demanded that the paintings be returned to their former German owners.

In point of fact, the return of these pictures in light of the well-known works of art taken from Germany to the Hermitage in Moscow [the museum was in Leningrad], would be better understood as representing America’s real stand in the world than thousands of words over the Voice of America and in our overt American publications.16

The German paintings of the Kaiser Friedrich collection were displayed briefly at the National Gallery in Washington and in thirteen American cities before being returned to Germany in 1948 per Clay’s suggestion. Senator Fulbright, a strong supporter of U.S. academic exchanges and other public diplomacy programs, became later a bitter critic of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty, which Clay helped to establish and supported.

One of Clay’s major achievements was the launch on February 7, 1946 of RIAS (Radio in the American Sector) in Berlin, which provided the Germans with local and international news and political commentary, as well as entertainment programming. Overall, neither General Clay nor General Dwight Eisenhower had much faith in the Office of War Information and, later, the State Department, being in charge of U.S. government-sponsored press outreach and radio broadcasting in occupied Germany or the Soviet Bloc. They both later participated in creating Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty.

At the end of World War II, the Office of War Information tried to establish a monopoly as a distributor of media news in Germany. However, in the presidential news conference on May 15, 1945, President Truman sided with General Eisenhower and confirmed that OWI Director Elmer Davis incorrectly stated that his agency would control access of U.S. media to the Germans living under the American occupation. Elmer Davis tried to extend the OWI’s reach in post-war Germany and received an angry reaction from General Dwight Eisenhower, who was then the Military Governor of the U.S. Occupation Zone, but President Truman described it only as a misunderstanding between OWI and military officials.17

After retiring from the military, General Clay later served as the national chairman of the Crusade for Freedom, which with then-secret funding through the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), helped to create Radio Free Europe, which soon became the number one Western broadcaster in most of the countries of East-Central Europe.18

General Clay said in a 1954 magazine advertisement for Radio Free Europe that, unlike the Voice of America, RFE was “not bound by diplomatic limitations.” He was right on that point. He was also right when in response to the question of why Radio Free Europe is so important to Americans, he answered:

Because it is devoted to the single most important job in the world–to help keep World War III from happening. If 70,000,000 people in the six Iron Curtain countries continue to resist Soviet tyranny, the Kremlin is kept off balance in one of the most strategically sensitive areas in the world.”19

To the question of what is the difference between Radio Free Europe and the Voice of America, his answer was:

The Voice of America is run and paid for by the Government. Radio Free Europe is operated as an independent American enterprise by a committee of private citizens. It is people talking to people–Poles telling the truth to Poles, Czechs and Slovaks telling the truth to Czechs and Slovaks, etc. It is not bound by diplomatic limitations. The Voice of America broadcasts to many countries and can only devote a limited amount of time each day to any one country. But Radio Free Europe’s ‘Voice of Free Czechoslovakia,’ for example, broadcasts about 20 hours each day to Czechoslovakia alone.”20

Testifying on February 28, 1946, before the subcommittee of the House of Representatives Committee on Appropriations reviewing the Department of State Appropriations Bill for 1947, Benton stressed the importance of shortwave radio programs in communicating with foreign audiences but confirmed that the Voice of America still did not have Russian-language broadcast to the Soviet Union:

Thus, Moscow cables:

“Radio is the only medium through which the United States of America can speak freely and directly to the Soviet people.”

As I reported to you yesterday, we are broadcasting to Russia only in English, though some of the other languages may go in, too. It is an important question as to whether we should now begin to broadcast also in Russian.21

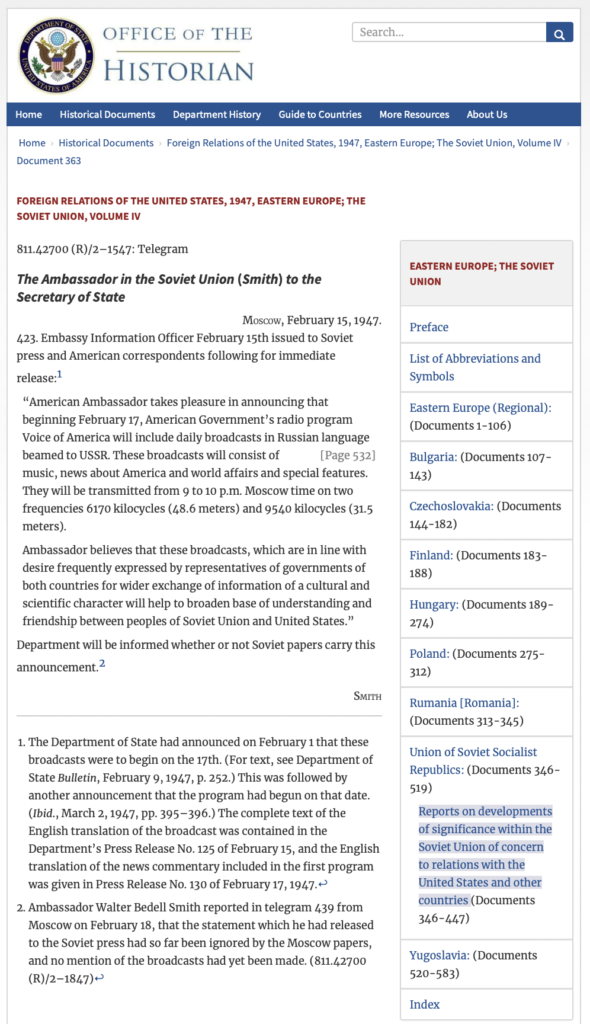

Benton would later fully support the launch of VOA Russian broadcasts, which aired for the first time on February 17, 1947. However, the VOA Russian Service still refrained for a few years from direct criticism of Stalin and the Soviet Union. The Truman administration gave the job of confronting the Soviet and other communist propaganda to Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberation (later renamed Radio Liberty).

The Truman White House became increasingly unhappy with Voice of America programs to Russia and the rest of the Soviet Bloc as they developed under Benton and supported the CIA’s efforts to launch radio broadcasting to the Soviet Bloc without a direct official link to the U.S. government. According to Edward Carleton Helwick, Jr., who had worked for VOA as an English-language writer-producer and later compared VOA programs in 1947 with those in 1950-1953, VOA’s first Russian-language broadcast did not include, outside of the newscast, any criticism of Soviet leaders or analysis of human rights issues under communism. Helwick also observed that mainstream U.S. media outlets were not impressed with the direction and tone of the first VOA Russian broadcast from New York.

It was evident from newspaper accounts that the broadcast in America, at least, was received with something less than enthusiasm. Typical of the reactions was the New York World Telegraph headline, “Russians Restrain Joy Over U.S. Broadcast.”22

The U.S. diplomat in charge of setting up the VOA Russian Service, Charles W. Thayer, who was later VOA Director (1948-1949), did not believe in confronting the Soviet regime. He was not convinced that Stalin was responsible for some of the mass murders he had committed.23 Thayer recruited as a volunteer a former Office of War Information journalist Kathleen Harriman who had helped to spread Stalin’s lies about Katyn during World War II when she was in Moscow accompanying her father, W. Averell Harriman, then President Roosevelt’s ambassador to the Soviet Union.24 She played only a minor role in the launch of VOA Russian broadcasts and later admitted while testifying before a congressional committee that she was wrong as a journalist in accepting as true the Soviet propaganda lies about the Katyn massacre. She was not the only one among OWI and VOA journalists and senior officials who were duped by Soviet propaganda or knowingly spread Stalin’s lies.

According to a declassified confidential State Department memorandum of January 25, 1951, written by U.S. diplomat Chester H. Opal who had served in Warsaw after World War II as an Information Officer from 1946 to 1949, Charles Thayer was uncertain whether the Russians were the actual perpetrators of the Katyn massacre, a World War II Soviet war crime against Polish military officers and members of the Polish intelligentsia that claimed about 22,000 lives. In a memorandum addressed to Walter Schwinn, who also had served in Poland, Opal noted:

I should like to recall that Charles Thayer, when he was in Warsaw, stated that he had spent a month of intensive official investigation of the Katyn case and had reported he was not convinced one way or another.25

Thayer was a controversial figure as the first head of the VOA Russian Service and later as the VOA director, but in an official Voice of America publication, VOA Authors: 75 Years of After-Hours Wisdom, he is presented only as an accomplished VOA manager, a diplomat, and a victim of the anti-Soviet hysteria in the 1950s.

Thayer returned to the Foreign Service after Voice of America, serving in several consular positions in Germany until 1953. Thayer was forced to resign from government service through the efforts of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI and Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s Red Scare and Lavender Scare campaigns.26

Early VOA Russian broadcasters working under Thayer were not allowed to criticize the Soviet Union, as one of them, Helen Zhemchuzhny Bates Yakobson (1913-2002), noted in her memoir published in 1994.

In those early years, VOA programs attempted to give full and impartial reports of life in the United States, including confessions of our shortcomings and faults. No direct criticism or attacks on the Soviet system were permitted. After all, they had only recently been our allies. But as the Cold War intensified, VOA responded and became openly and vigorously critical of the Soviet system and government.27

Before the first Voice of America Russian broadcast went on the air in February 1947, Associated Press had reported that “all staff members are reported to have been carefully screened to eliminate any with either Communist or anti-Soviet feelings.” The AP report suggested that Assistant Secretary of State William Benton closely supervised the selection of the Voice of America’s Russian Service’s initial staff to ensure that neither Communists nor anyone highly critical of the Soviet Union would be hired. The headline in The Mobile Press Register on February 2, 1947, read, “U.S. To Start Radio Programs Aimed At Reds.” The AP report said that Russian-language Voice of America broadcasts to the U.S.S.R. would start on February 17. The subheadline said, “State Department Directs News, Music, Features To Inform Russians.” But the most revealing information about the future content of the program was to be found in the subheading, “Non-Partisan Staff.” It would have been hard to imagine Office of War Information government executives in charge of Voice of America broadcasts in 1942 announcing that the newly-selected staff of the VOA German Service would not harbor either Nazi or anti-Nazi feelings. The Voice of America in 1947 was still under the supervision of officials who did not believe that Stalin, like Hitler, was also a mass murderer.

The Russian section of the international broadcast division of the State Department will have an initial staff of 12 permanent employees, all American citizens.

Organization of this staff is understood to have been a major concern of Assistant Secretary of State William Benton. All staff members are reported to have been carefully screened to eliminate any with either communist or anti-Soviet feelings. 28

It was not entirely true that there were no anti-communists in the first group of VOA Russian broadcasters. One of them was Nicolas Nabokov, a former professor of philosophy at St. John’s College in Maryland. A first cousin of Russian-American writer Vladimir Nabokov of Lolita fame, he was undoubtedly anti-Soviet and anti-communist, as were many other VOA Russian Service broadcasters, but in 1947, they were not allowed to criticize Stalin or the Soviet system. The change in programming to permit such criticism came in 1950, but already in 1948, a strongly anti-communist Soviet defector, General Alexander Barmine, joined the VOA Russian Service and soon became its chief.

The timid nature of the first VOA Russian broadcasts was noted in debates in Congress. On June 13, 1947, Rep. John Taber (R-NY) said with considerable exaggeration that the Voice of America’s first program to Russia in February was a “totalitarian philosophy broadcast.” The VOA broadcast did not openly support the totalitarian communist system in the Soviet Union and the Soviet Bloc, but it did not expose its human rights violations or condemn them. Congressman Taber commented on the VOA budget that “if it was a bill providing for the Voice of America, and it was honestly to be the Voice of America, I would support it.

Their very first broadcast to Russia was a totalitarian philosophy broadcast. I have had in my hands, and I have in my office 500 broadcasts, and out of the whole 500 I defy any man to find one that would do America a bit of good, and he would find many that would do a lot of harm.29

William Benton’s early professional background was in advertising. He believed in persuasion and selling America to the world through the Voice of America and the State Department’s public diplomacy programs rather than aggressively confronting Soviet and other communist propaganda. By 1946, Benton became convinced that Voice of America radio broadcasts to Russia were needed, but he did not know what type of programming they should include. Benton relied on Charles Thayer and other State Department Soviet experts to find the right formula. Many anti-communists, especially among conservative Republicans, criticized Benton’s and Thayer’s approach.

In what many have been an indirect rebuke of Benton’s policy direction on public diplomacy and Voice of America broadcasting to the Soviet Bloc, former U.S. Ambassador to Poland Arthur Bliss Lane, who became a champion of creating Radio Free Europe and advocated personnel and programming reforms at VOA, wrote in his book, I Saw Poland Betrayed, published in 1948, that he did not object to radio broadcasts to the Soviet Union and other Soviet Bloc nations if they would have had the right content, but concluded that they did not.

If appropriate material is used which will bring hope and cheer, instead of intensifying despair, there is much of a constructive nature that we can do. But the wisdom of statesmanship, not that of salesmanship, is a requisite.30

Ambassador Bliss Lane also stressed:

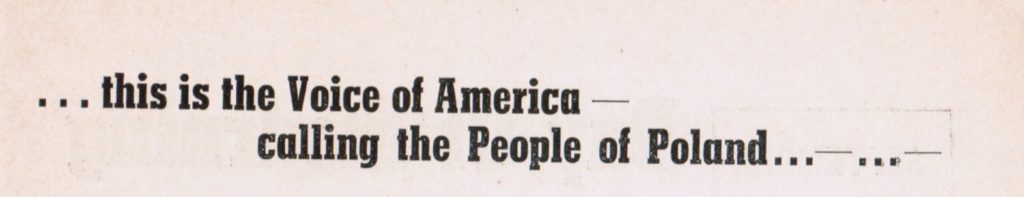

As for radio broadcasts beamed to Poland as the “Voice of America,” my opinion of their value differed radically from that of the authors of the program in the Department of State. …I felt that the Department’s policy to tell the people in Eastern Europe what a wonderful democratic life we in the United States enjoy showed its complete lack of appreciation of their psychology. And, especially in Poland, which had suffered through six years of Nazi domination, it was indeed tactless, to say the least, to remind the Poles that we had democracy, which they also might again be enjoying, had we not acquiesced in their being sold down the river at Teheran and Yalta.31

Ambassador Bliss Lane urged the State Department to hire anti-communist refugee journalists from Eastern Europe to replace pro-Soviet editors and broadcasters. One of them, hired at his recommendation, was Zofia Korbońska, a former member of the anti-Nazi resistance in Poland.

Thanks to the departure of pro-Soviet writers and editors and the hiring of broadcasters like Zofia Korbońska, the Voice of America became more effective in broadcasting to the Soviet Bloc. American journalist and writer Eugene Lyons, who had worked as a reporter in the Soviet Union in the 1930s, was initially a pro-communist fellow traveler and interviewed Joseph Stalin, but later became a strong critic of Communism and Soviet Russia, became convinced that the Voice of America employed in its early years pro-Kremlin “subversives” because he knew many of them from the time he was moving in their circles. He was also convinced that by 1954, these individuals were no longer employed by the Federal government.

Without doubt, some “subversive” individuals formerly found their way into VOA, as into other agencies in Government. Fortunately, the Voice has cleared house. Ardent anti-Communists on the inside are now convinced that no known Communists or Communist sympathizers remain.32

At the conclusion of his 1954 Reader’s Digest article, Eugene Lyons wrote:

That the Voice has shortcomings is admitted. But the remedy is not to destroy this one official channel for reaching the freedom-loving peoples of the world. The remedy is to improve and strengthen the Voice.33

An ex-Marxist and later anti-Communist, Bertram Wolfe, whom the Truman administration hired in the early 1950s to help reform the VOA programs and counter Soviet propaganda, could not find a single Voice of America English-language writer capable of understanding the deep need for religious freedom among VOA audiences behind the Iron Curtain. He had to write religious programs himself, even though he was an atheist.

When I went to work for the Voice of America in the period from 1950 to 1954, religious leaders and believers were being framed, tortured, and sent to concentration camps in all the countries under Communist rule in Eastern Europe. After trying to get my script writers to write effective radio broadcasts to defend the religious freedom of the churchmen and devout believers who were being thus persecuted, I found that I had to write the scripts myself to get the requisite feeling into them. I did not believe what the persecuted believed, but I did believe in their right to freedom to harbor and practice their beliefs without interference.34

As the answer to harsh Soviet propaganda attacks on the United States and its allies and the mounting criticism that his administration failed to address them, President Truman unveiled the “Campaign of Truth.” In a foreign policy speech on April 20, 1950, to members of the American Society of Newspaper Editors, he presented a multi-faceted U.S. government’s international information program designed to inspire journalists, including Voice of America’s federal employees of the Department of State, to offer more vigorous and more effective resistance to Soviet propaganda and communist influence. “Everywhere that the propaganda of the Communist totalitarianism is spread, we must meet it and overcome it with honest information about freedom and democracy,” Truman said. He also alluded to the media’s criticism of his foreign policy and indirectly to criticism of the Voice of America. “Foreign policy is not a matter for partisan presentation,” Truman said in his speech to American journalists.

After President Truman’s “Campaign of Truth” speech, Secretary of State Dean Acheson said in his semiannual report to Congress on the International Information and Educational Exchange Program for the period July 1 to December 31, 1950, that “Operationally, launching of the Campaign of Truth was reflected at the outset more in sharpened program content and specialized radio treatment than in marked increases in broadcast operations.”35

Acheson indirectly agreed with critics that earlier VOA programming to the Soviet Union under William Benton and for a few more years after this departure was not well-planned to meet the Soviet propaganda challenge. Acheson mentioned the Soviet jamming of VOA broadcasts, but the jamming was not the main factor in changing VOA’s programming policy. The Stalinist regime was just as murderous in 1947, when the VOA Russian broadcast was finally started, as it was in the second half of 1950, the period covered by Acheson’s report to Congress. VOA programming needed to reflect the reality of Soviet and communist totalitarianism in the Soviet Union and in other countries, which it failed to do earlier.

In the broadcasts to Eastern Europe, greater program variety was introduced; more liberal use was made of anti-Communist political satires and exposés, and of the documentary and dramatized technique.

The systematic jamming of VOA’s Russian broadcasts greatly influenced both their content and format. Music and dramatizations were eliminated, and the salient portions of the programs were repeated around the clock. Later in the period, when a partial neutralization of the Soviet jamming effort was achieved, some of the dramatized material was restored. An increasing number of Soviet DP’s came to the microphones of VOA to tell their story.36

While Acheson admitted that VOA’s program content was previously not sufficiently sharp, progress to fix the problem was not quick within the government bureaucracy. Whistleblowers and members of Congress continued to report questionable programming at VOA for at least two more years.37

BBC, which during World War II broadcast occasional messages in Russian but did not have regular Russian-language broadcasts, established its Russian Service and started broadcasting in Russian on March 24, 1946.

In February 2017, the Voice of America presented a sanitized version of the history of the VOA Russian Service to mark the 70th anniversary of its first Russian-language broadcast launch. The 2017 Voice of America report did not mention any of the controversies of the VOA Russian Service’s early years or the censorship by the VOA management in the 1970s of Russian dissident writer Alexandr Solzhenitsyn.

VOA NEWS REPORT

VOA Russian Service Celebrates 70 Years

By Marissa Melton

February 17, 2017 5:34 AM

UPDATE February 17, 2017 8:02 PM

“Hello, this is New York calling.” The words, in Russian, hit Russian airwaves on Feb. 17, 1947 — the first Russian broadcast of the Voice of America.

The broadcasts were an integral part of the United States’ propaganda campaign against the Soviet Union, which was seen as the new threat once World War II was over in 1945.

VOA, which began during the war as a way to convey American news and policies to occupied areas, told its Russian listeners it was meant to “give listeners in the USSR a picture of life in America.” Like its other services, VOA’s Russian service meant to give its audience the “pure and unadulterated truth” about life beyond Soviet borders.

News, music, human interest

The first programs contained a mix of news, music and human interest stories, with programs skewing more and more toward music, particularly jazz, a distinctly American musical innovation that gained considerable popularity in Russia and elsewhere overseas.

VOA broadcasts by jazz expert Willis Conover, known as Voice of America Jazz Hour, were especially popular. Conover also helped produce jazz concerts at the White House and is credited with helping to desegregate Washington, D.C., jazz clubs.

But the Soviet government fought back. In April 1947, just over two months after the broadcasts started, the Soviets began jamming the radio signal electronically.

Critics of VOA complained that the signal interference made it very difficult to gauge the effectiveness of the American broadcasts.

Elez Biberaj, chief of VOA’s Eurasia division, said the Soviet efforts to block VOA’s influence went even farther than that.

“Russians caught listening to VOA faced various forms of punishment, including imprisonment,” Biberaj said.

Regardless, defectors from the Soviet Union, as well as Western embassies in Moscow and travelers who visited the area, reported that the VOA broadcasts were well-received by their Russian audience.

“For decades,” Biberaj said, “VOA served as an outlet for Russian dissent and provided an alternative source for the flow of information and ideas, helped discredit the official Communist propaganda, and encouraged democratic elements. There is ample evidence that demonstrates the impact of VOA’s Russian broadcasts and the important role that these broadcasts played in the demise of Communism.”

VOA continued to play an important role in the region after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. Biberaj said while Russia made significant progress on the road to democracy in the 1990s, it has since slid backward with media largely under state control, and the suspicious deaths of journalists and human rights activists.

“The lack of truly alternative voices in the media has had serious consequences for the democratization of the Russian society,” Biberaj said. “And it is here that VOA comes into play, filling an important vacuum by serving as an alternative voice and meeting the audience’s informational needs.”

Programming changes

In 2008, VOA was denied placement on Russia’s media outlets, so the online service was expanded. It now reaches its Russian-speaking audience with video streaming, social media products, expert blogs, and user-generated content and feedback. In addition to that, Biberaj said, VOA increased its Russian-language television programming.

As a result, VOA’s Russian service now reaches 3.1 percent of Russian adults each week, and the number of adults who consider VOA’s content “trustworthy” grew from 56 percent in 2015 to 65 percent in 2016. Last year VOA’s Russian website registered nearly 15 million visits.

“The Russian service debunks the Kremlin’s strident anti-American propaganda with fact-based content; offers in-depth coverage of issues vital to U.S. national interests; gives an accurate and comprehensive portrait of America and its policies and institutions; and targets potential change agents in Russia,” Biberaj said.

Those agents include “opposition figures, business leaders with a strong stake in integrating Russia into the global economy,” he said, “and the many Russians — now largely silent — who favor putting Russia back on a path that embraces democracy, civil society, and rule of law, and respect for human rights.”

END OF VOA REPORT

In 1982, Nobel Prize-winning author Alexandr Solzhenitsyn published an article in National Review highly critical of VOA. In the article titled “The Soft Voice of America,” Solzhenitsyn wrote:

Thus, instead of effectively giving us news, VOA helps to keep us ignorant. In order not to violate State Department policy, it gives us a stone in place of bread.38

Solzhenitsyn also wrote in National Review:

In December 1973, when I was still in the Soviet Union, The Gulag Archipelago was published in the West. VOA—or, rather, one VOA announcer—read an excerpt from Gulag on the air. Immediately, Radio Moscow started screaming that VOA had no right to interfere in the internal affairs of the Soviet Union, that the broadcast had fouled the international atmosphere. And what did VOA do? With the agreement of the State Department, it took the announcer off that assignment and forbade the reading of The Gulag Archipelago to Russia! More, for several years it was forbidden to quote Solzhenitsyn on VOA, so as not to discredit Communist propaganda. My book was written for Russians. Millions of copies were read in the West, but it could not be read to our Motherland! 39

The VOA Russian Service was able to quote from Solzhenitsyn and use short excerpts from his books, but during the Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations, the management banned interviews with the writer and would not allow longer readings from The Gulag Archipelago and his other books. Solzhenitsyn reconciled with VOA during the Reagan administration after these bans were lifted.40

Department of State Bulletin, February 9, 1947, p. 252.

Department of State Bulletin, March 2, 1947, pp. 395-396.

NOTES:

- Sidney Hyman, The Lives of William Benton (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1969), p. 341.

- William Benton, This Is The Challenge: The Benton Reports of 1956-1958 On The Nature Of The Soviet Threat (New York: Associated College Presses, 1958), “The Author” on the book’s jacket.

- Ted Lipien, “Mira Złotowska – Michałowska — Was She VOA’s Communist ‘Mata Hari’?,” Cold War Radio Museum(blog), December 10, 2019, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/mira-zlotowska—michalowska—-was-she-voas-communist-mata-hari/.

- Ted Lipien, “Communist Secret Police in Poland Spied on Voice of America’s Willis Conover to Shut down Radio Free Europe,” Ted Lipien (blog), August 16, 2020, https://tedlipien.com/blog/2020/08/16/communist-secret-police-in-poland-spied-on-voice-of-americas-willis-conover-to-shut-down-radio-free-europe/.

- Ted Lipien, “Voice of America Polish Writer Listed As His Job Reference Stalin’s KGB Agent of Influence Who Duped President Roosevelt,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), February 12, 2020, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/voice-of-america-polish-editor-listed-stalins-kgb-agent-of-influence-as-job-reference/.

- Ted Lipien, “First VOA Director Was a Pro-Soviet Communist Sympathizer, State Dept. Warned FDR White House,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), May 5, 2018, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/state-department-warned-fdr-white-house-first-voice-of-america-director-was-hiring-communists/.

- Tadeusz Lipien, “Howard Fast – Chief of Voice of America News Who Won the Stalin Peace Prize, Voice of America – 80 Years of Hidden History,” Voice of America – 80 Years of Hidden History (blog), accessed January 26, 2022, https://www.voa80.com/2021/12/21/howard-fast-chief-of-voice-of-america-news-who-won-the-stalin-peace-prize/.

- Oliver Carlson, Radio in the Red (New York: Catholic Information Society, 1947), p. 7.

- “How a Refugee Journalist Exposed Voice of America Censorship of the Katyn Massacre,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), April 16, 2018, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/how-refugee-journalist-exposed-voice-of-america-katyn-censorship/.

- Julius Epstein, Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 81st Congress, Second Session, Appendix. Part 17 ed. Vol. 96. August 4, 1950, to September 22, 1950 (Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1950) pp.

A5744-A5745. - Julius Epstein, “The O.W.I. and the Voice of America,” a reprint from the Polish American Journal, Scranton, Pennsylvania, 1952.

- Hyman, The Lives of William Benton, p. 341.

- Hyman, The Lives of William Benton, p. 347.

- Hyman, The Lives of William Benton, p. 348.

- Lucius D. Clay, Decision in Germany (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1950), p. 283.

- Hyman, The Lives of William Benton, p. 318.

- Curator, “President Truman and General Eisenhower Shut Down OWI Attempt To Control U.S. Media Access To Occupied Germany,” Cold War Radio Museum, accessed December 28, 2022, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/timeline/president-truman-and-general-eisenhower-shut-down-owi-attempt-to-control-u-s-media-access-to-occupied-germany/.

- Curator, “Radio Free Europe Fundraising During the Cold War – Cold War Radio Museum,” accessed December 28, 2022, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/radio-free-europe-fundraising-during-cold-war/.

- In a one page ad placed in Ladies’ Home Journal in March 1954, one of many such ads commissioned by the Crusade for Freedom, General Lucius D. Clay answered nine questions about Radio Free Europe.

- Ladies’ Home Journal, March 1954.

- William Benton, Hearings Before the Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations on the Department of State Appropriation Bill for 1947, House of Representatives, 79th Congress (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1946), p. 492, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112055335746?urlappend=%3Bseq=500%3Bownerid=13510798903948865-504.

- Edward Carleton Helwick, Jr., “Policy problems of the Voice of America: 1945-1953.” Master Thesis, Department of Political Sciences, University of Southern California, June 1954, pp. 218-219.

- Ted Lipien, “Secret Memos on How Voice of America Was Duped by Soviet Propaganda on Katyn Massacre,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), May 2, 2021, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/secret-memos-on-how-voice-of-america-was-duped-by-soviet-propaganda-on-katyn-massacre/.

- Charles W. Thayer, Diplomat (London: Michael Joseph, 1959), p. 187.

- “Pro-Stalin Voice of America Propaganda Revealed in 1984 VOA Interview with Józef Czapski,” Cold War Radio Museum, September 4, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/stalins-american-voice/.

- Alan L. Heil Jr. and Michelle D. Harris, “VOA Authors: 75 Years of After-Hours Wisdom,” InsideVOA, p. https://docs.voanews.eu/en-US-INSIDE/2019/11/15/df7f3a8a-f63e-46e1-9305-eed04ec40047.pdf

- Helen Yakobson, Crossing Borders: From Revolutionary Russia to China to America (Tenafly, N.J: Hermitage Publishers, 1994), p. 146.

- AP report in The Mobile Press Register, “U.S. to Start Radio Programs Aimed at Reds: State Department Directs News, Music, Features to Inform the Russians,” February 2, 1947, p. 1.

- John Taber, 93 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 93, Part 12 (June 13, 1947 to December 19, 1947), p. 6965, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt6/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt6-2-2.pdf.

- Blane, Arthur Bliss. I Saw Poland Betrayed: An American Ambassador Reports to the American People (Indianapolis and New York: Bobbs-Merrill Company), 1948, p. 219.

- Lane, I Saw Poland Betrayed: An American Ambassador Reports to the American People, p 219.

- Eugene Lyons, “How Good Is the Voice of America,” Reader’s Digest, June 1954, p. 91.

- Lyons, “How Good Is the Voice of America,” p. 92.

- Bertram D. Wolfe, A Life in Two Centuries: An Autobiography (New York: Stein and Day, 1981), p. 81.

- Dean Acheson, U.S. Secretary of State, “Launching the Campaign of Truth–First Phase: Sixth Semiannual Report of the Secretary of State to Congress on the International Information and Educational Exchange Program, July 1 to December 31, 1950,” Department of State Publication 3479, December 1951, p. 3. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d03562370p?urlappend=%3Bseq=8.

- Dean Acheson, U.S. Secretary of State, “Launching the Campaign of Truth–First Phase: Sixth Semiannual Report of the Secretary of State to Congress on the International Information and Educational Exchange Program, July 1 to December 31, 1950,” Department of State Publication 3479, December 1951, p. 4. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d03562370p?urlappend=%3Bseq=11.

- “Voice of America 1951 – ‘Drab’ ‘Unconvincing,’” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), February 24, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/voice-of-america-1951-drab-and-unconvincing-rep-wigglesworth-quotes-voa-listeners-in-poland/.

- Ted Lipien, “SOLZHENITSYN Target of KGB Propaganda and Censorship by Voice of America,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), November 7, 2017, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/solzhenitsyn-target-of-kgb-propaganda-and-censorship-by-voice-of-america/.

- Lipien, “SOLZHENITSYN Target of KGB Propaganda and Censorship by Voice of America.”

- Mark G. Pomar, Cold War Radio: The Russian Broadcasts of the Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (Lincoln: Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, 2022) [Amazon Link]