Summary

David Sarnoff, the pioneer of the radio and television industry in the United States and the founder of the NBC network, was most likely the first American with access to the White House to present a comprehensive plan for U.S. government-funded international radio broadcasting and one of the first to suggest for it the “Voice of America” name. However, when the first programs with anti-Nazi and anti-Japanese propaganda went on air to Europe in 1942, the “Voice of America” name was not used.

The first U.S. government-funded radio broadcasts, beginning in early 1941, were to Latin America using six private American companies. The agency in charge of the initial U.S. government’s overseas broadcasting operations was the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (CIAA), headed by Nelson A. Rockefeller. The name “Voice of America” was never used for international radio programs to Latin America before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

David Sarnoff of NBC suggested to Nelson Rockefeller in 1940 that all existing private U.S. stations broadcasting to Latin America be consolidated into one group. Eventually, NBC and CBS, program providers through government contracts, agreed on simultaneous broadcasts to Latin America to achieve greater coverage. Programs to Europe initiated separately in February 1942 by the Foreign Information Service (FIS) within the Office of the Coordinator of Information (CIO) started to use the “Voice of America” name but not until later in the war.

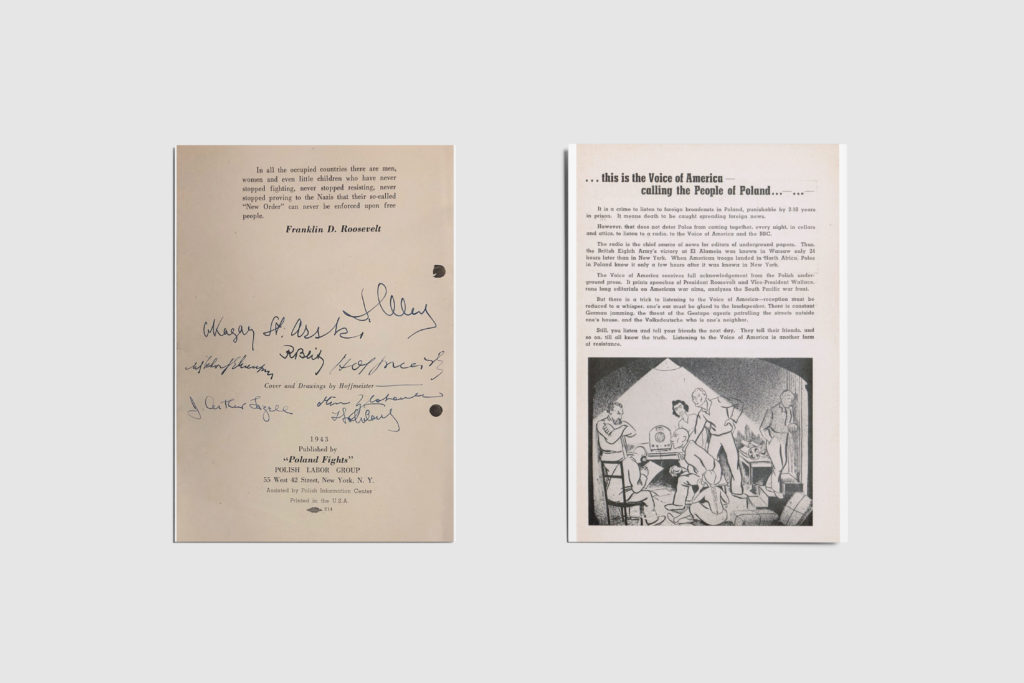

U.S. government-sponsored broadcasts to the rest of the world except to Latin America were absorbed in June 1942 by the Office of War Information (OWI), headed by Elmer Davis. In addition to anti-Nazi propaganda, they also included a heavy dose of disinformation to whitewash Stalin and his repressive Soviet communist regime to protect America’s military alliance with Russia (Hitler’s erstwhile ally).

The “Voice of America” name would not be officially adopted for the broadcasts until a few years after the end of World War II, although by March 1942, some OWI radio services started introducing their programs as VOA, and some officials started referring to them by using the name in official correspondence.

David Sarnoff was alarmed by both fascist and communist propaganda, but while serving as an advisor on communications to General Eisenhower during the war, he did not make his views about the Soviet Union public. As Stalin reneged on most of the unenforceable and unenforced promises made to Roosevelt and Churchill at the Tehran and Yalta wartime conferences, Sarnoff recommended countering Soviet propaganda in the early years of the Cold War. Radio Free Europe (RFE) and Radio Liberty (RL) successfully implemented most of his ideas. He and General Eisenhower served on the board of the Free Europe Committee, a CIA front organization that helped to establish Radio Free Europe and generated public support for its broadcasts.

The Voice of America also used some of Sarnoff’s ideas for post-war broadcasting on a smaller scale during President Truman’s “Campaign of Truth” in the early 1950s. However, toward the end of the Eisenhower administration, some United States Information Agency (USIA) diplomats, American-born VOA officials, and VOA editors gave up on most of Sarnoff’s recommendations for confronting Soviet propaganda through Voice of America broadcasts. Most likely because of his strong anti-communism, which David Sarnoff was not afraid to express publicly before and after World War II, and because he was never a journalist, he is not mentioned in books and articles written about the Voice of America, even though he had a much greater influence on U.S. international broadcasting during the Roosevelt, Truman, and Eisenhower administration than the CBS broadcaster Edward R. Murrow who became President Kennedy’s USIA director. Sarnoff tried unsuccessfully to recruit Murrow to work for NBC and defended him when Senator Joseph McCarthy falsely accused him of pro-Soviet sympathies.

Before Truman’s “Campaign of Truth” reforms, VOA still censored strong criticism of the Soviet regime until about 1951 and, after his presidency, to a limited degree in later years. Sarnoff was strongly opposed to the appeasement of the Soviet Union and its satellite states. Limited censorship of some of the most effective critics of communism—Americans and Russians like Nobel Prize-winning author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn—did not entirely disappear at the Voice of America until the start of the Reagan administration in 1981.

Not all USIA Foreign Service officers serving in senior management positions at the Voice of America tried to interfere with VOA news for reasons of diplomacy. Not all American-born VOA managers and editors resisted hard-hitting journalism, but many did. Fortunately, RFE and RL were spared such interference and restrictions.

Reagan, who also strongly supported Radio Free Europe, was the second U.S. president after Truman who agreed with most of Sarnoff’s views about communism and the Soviet Union. Reagan’s appointees at USIA and VOA allowed anti-communist refugee broadcasters much greater freedom, providing them with resources to help peacefully defeat communism, beginning in Poland when I was in charge of the Polish Service.

Sarnoff died in 1971, but during the Solidarity trade union’s struggle for democracy, we used many of his concepts to increase the listenership to VOA’s Polish-language programs in Poland nearly fivefold to well over 50 percent of the adult population. We did it quietly against the fears and advice of longtime USIA and VOA officials and some American journalists who predicted that Reagan’s much harder line against communism and Russia would make the Voice of America ineffective and ruin its credibility.

Some pre-Reagan Voice of America officials and journalists, often highly partisan, admired the VOA’s founding fathers. At least some must have known that many of the early VOA officials and journalists had followed in the footsteps of the fellow traveler Anglo-American New York Times Moscow correspondent Walter Duranty. Some may also have known that pro-Stalin communists, including a future Stalin Peace Prize winner, were in charge of the Voice of America programs during World War II but hid that fact from the American public and their employees.

During World War II, the Voice of America employed many pro-Soviet propagandists. After the war, refugee journalists, who were former victims of Hitler’s and Stalin’s repressions and replaced some of those who later served the communist regime in Eastern Europe, knew more than enough about the Gulag slave labor camps not to be deceived by the official distortions of their own organization’s history. They practiced journalism in opposition to totalitarian ideologies and followed the example of other anti-communist journalists, American and foreign-born, including some former communists and Soviet sympathizers who became strongly opposed to communism—Bertram Wolfe, Julius Epstein, and Eugene Lyons.

Their ideas were not much different from Edward R. Murrow’s strategy to fight against communist propaganda, especially in Cuba, although, as the USIA director during the Kennedy and early Johnson administrations, he only expressed them in secret memos. Unlike almost all liberal mainstream American journalists, including those working for VOA in the 1940s, Murrow was not duped by the Soviet propaganda lie about the Katyn massacre of thousands of Polish military officers—the crime, which Stalin personally ordered but falsely blamed on the Germans.

Neither Sarnoff nor Murrow advised distorting the truth, mixing news with commentary, or using crude propaganda. Sarnoff’s contributions to U.S. international broadcasting, like those of later anti-communist refugee journalists, have been ignored or greatly diminished. Murrow is justly presented as a defender of truthful journalism, but his behind-the-scenes propaganda battle with the Soviets as the USIA chief is rarely mentioned.

The distortions and the ignorance of history, especially at the Voice of America and in the rest of the U.S. government, have damaged post-Cold War journalism and helped Vladimir Putin wage his war of aggression and imperial territorial expansion against Ukraine. The damage has extended well beyond the Voice of America and its current federal overseer, the U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM).

In November 2003, the Pulitzer Prize Board, whose then-membership read like the Who’s Who of the elite American media and academia establishment, voted not to revoke Walter Duranty’s Pulitzer Prize despite his pro-Soviet propaganda and lies about the Stalin-engineered famine in Ukraine that took millions of lives in the 1930s. Because of the decades-long suppression of information about the Soviet propaganda influence, at least some of those Pulitzer Prize Board members who had voted in 2003 not to strip Walter Duranty of his Pulitzer Prize and later attained positions of leadership in the U.S. government’s international broadcasting may have been unaware of the entire history of Stalin’s Great Terror, the Ukraine famine, and the Duranty-led attack on Welsh reporter Gareth Jones, one of the few journalists who was telling the truth about the Holodomor extermination of peasants of Ukrainian, Russian, and other nationalities.

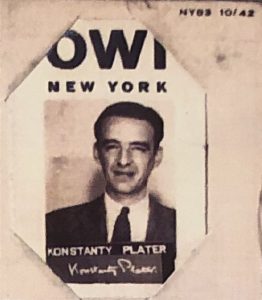

Joining Duranty in his attack on Jones were other elite American and British correspondents in Moscow. One of them, Eugene Lyons, revealed later in his 1937 book Assignment in Utopia that they had all deliberately lied about the imposition of Soviet rule, the Ukrainian famine, and Gareth Jones. Did members of the 2002-2003 Pulitzer Prize Board know about Eugene Lyons’s admission of guilt before making their decision? Have they heard of other courageous journalists like a Jewish refugee from Nazism and a former communist, Julius Epstein, former communist Bertram Wolfe, and Homer Smith, an African-American journalist in the Soviet Union who had exposed Soviet propaganda lies? Did they know about Konstanty Broel Plater, the only World War II-era Voice of America broadcaster known to have resigned in protest against VOA’s airing of Soviet propaganda lies?

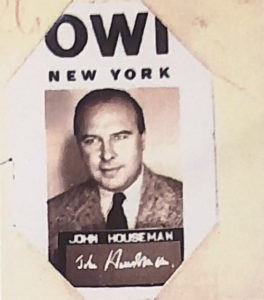

The U.S. government officials deceived by Putin’s propaganda may not have paid sufficient attention to the memoirs of U.S. diplomats George Kennan, Charles Bohlen, and Foy Henderson, who noted the dishonesty of news reporting from the Soviet Union by left-leaning Western journalists during Stalin’s rule. They may have never heard of Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles’s successful effort to remove John Houseman from his VOA job. Houseman was later inaccurately proclaimed the first director of the Voice of America. Houseman was not in charge of program content but hired communists to fill VOA jobs.

The U.S. government officials also may not have known about David Sarnoff’s contributions to U.S. international broadcasting or Edward R. Murrow’s no longer secret Cold War USIA directives, in which he firmly advocated countering Soviet propaganda. The decades-long coverup of the Voice of America’s true history has implications for today’s American journalism, not just at VOA but also in private U.S. media.

What used to be largely the affliction of the American radical Left, Russian President Vladimir Putin and his propagandists managed to turn into an epidemic among radical right-wing Republicans and TV and social media pundits. Putin aims to do the same in spreading disinformation and influencing American leaders on the right and on the left as Stalin and other Soviet leaders had done. He has found that Tucker Carlson can spread the Kremlin’s message in the United States much more effectively than his own propagandists.

The same thing was done for Stalin by Walter Duranty at the New York Times, Voice of America’s Howard Fast, the Office of War Information director Elmer Davis, his deputy and VOA’s de facto director and FDR’s speechwriter and personal friend Robert E. Sherwood, former Moscow correspondent and VOA’s first program director Joseph Barnes, VOA’s chief radio producer John Houseman, OWI and VOA officials Wallace Carroll and Owen Lattimore, OWI’s liaison officer with Hollywood Nelson Poynter, and many World War II VOA broadcasters.

Apologists for these fellow travelers managed to hide that some of VOA’s early officials and journalists were fired or forced to resign even by the already highly pro-Soviet Roosevelt administration as General Eisenhower and FDR’s liberal friends and Russia experts in the State Department became alarmed by OWI’s and VOA’s excessive reliance on Soviet propaganda. These officials’ and journalists’ naive faith in Soviet communism made it easier for Stalin to mislead President Roosevelt, for FDR to mislead the American people about Stalin, and for the Soviet dictator to enslave East-Central Europe.

President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill decided the fate of seventy million East Europeans without the knowledge or agreement of America’s smaller allies in the coalition against Nazi Germany. It happened at the Tehran Big Three conference with Stalin at the end of 1943 and was confirmed at the Yalta conference in February 1944. Still, history might have taken a different turn if journalists like Duranty had not lied in the 1930s and the early 1940s and if the U.S. government’s World War II propagandists in the Office of War Information and the Voice of America had not covered up Stalin’s genocidal crimes. Perhaps millions of lives could have been saved in Russia, Ukraine, and elsewhere in Eastern and Central Europe, as well as the lives of American soldiers who died in Soviet-instigated wars in Korea, Vietnam, and other Cold War conflicts.

The 2003 Pulitzer Prize Board decision on Walter Duranty’s Pulitzer Prize confirms that no lessons were drawn about the dangers of dishonest journalism. Right-wing media pundits like Tucker Carlson and some Trump administration officials have been deceived by the lies of Russia’s current ex-KGB ruler just as easily as many left-leaning Western journalists and the Roosevelt administration officials were deceived by Stalin and his propagandists during World War II.

Our best and surest way to prevent a Hot War is to win the Cold War.

David Sarnoff, Program For A Political Offensive Against World Communism, April 5, 1955

Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

Introduction

According to David Sarnoff‘s biographer and his first cousin Eugene Lyons (both Sarnoff and Lyons were born in the same town to Jewish families in the pre-Bolshevik Russian Empire and emigrated to the United States when they were children), the president of the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) and the founder of the National Broadcasting Company (NBC), may have been the first person to use the words “Voice of America” in calling for U.S. government-funded and managed international radio broadcasts. The “generalissimo of the radio industry” and “father of television” in the United States had made his suggestion about the need for “Voice of America” radio before the start of World War II and before such U.S. government-produced radio programs were launched in 1942, although still at that time without the use of the Voice of America name. The name proposed by Sarnoff was not officially adopted until shortly after the end of World War II.

Eugene Lyons, important but because of his anti-communism forgotten figure in American journalism and political discourse, paid somewhat more attention to David Sarnoff’s interest in U.S. international broadcasting than his other biographer, businessman, and former RCA executive vice president Kenneth Bilby. Bilby attributed Sarnoff’s distaste for communism and Soviet Russia primarily to his cold-warrior mentality amplified by the prospect of lucrative government communications and military contracts for his company. Bilby saw Sarnoff as “a leader among the cold warriors, a wholehearted subscriber to the later brinkmanship of John Foster Dulles,” President Dwight D. Eisenhower‘s Secretary of State.1

But contrary to Bilby’s assumptions, Sarnoff’s anti-communism had deeper roots in his life experience and was more nuanced. The Jewish immigrant from Russia often stressed that eventual “liberation” was to be achieved peacefully and that countering communist propaganda and strong U.S. defense posture were needed to avoid a “hot war.” While he and many others used the badly-chosen word “liberation,” he saw it as the “hope of liberation” and the ultimate result of consistent American policy to oppose Soviet Russia and communist China. In a 1960 article in Life magazine, titled “Turn Cold War Tide in America’s Favor,” also included in a book, The National Purpose, with articles from Adlai Stevenson, Archibald MacLeish, James Reston, Walter Lippmann, and others, Sarnoff explained:

…in the conflict with Communism we must become the dynamic challenger rather than remain the inert target of challenge. Only then can freedom regain the initiative.2

He pointed out that few democratic leaders dared to speak of the coming collapse of the communist empire and instead used “such solacing and temporizing words as accommodation, modus vivendi, relaxing tensions and coexistence,” while Soviet and Chinese leaders constantly predicted the doom of capitalism and the Western world.3 The first U.S. president who adopted a new communications strategy vis-a-vis Soviet Russia according to some of Sarnoff’s recommendations, was Ronald Reagan, who took office ten years after Sarnoff’s death.

Lyons understood his cousin’s pro-freedom perspective based on their shared experience of being born in imperial Russia more than Bilby and shared a heightened sense of injustice, prejudices, and repression with his cousin. Lacking the same immigrant experience, Bilby was somewhat dismissive of Sarnoff’s anti-communism and did not cover as much of Sarnoff’s involvement with U.S. government-funded broadcasters as in Lyons’s book. But Bilby noted in 1986, fifteen years after Sarnoff died in 1971:

… his concept of penetrating the Iron Curtain with broadcast messages won broad support. Out of it later emerged the Voice of America and Radio Free Europe, to both of which services Sarnoff felt a parental tie.4

Bilby was likely referring to the Voice of America as it developed several years after the end of World War II rather than the U.S. government radio broadcasts of the earlier period aired under various other names. Sarnoff’s idea had a role in their launch, but they did not follow his recommendations for opposing the communist and Soviet totalitarian ideology. They supported it by presenting it as progressive and democratic.

Sarnoff’s strong opposition to communism and the Soviet Union may have also resulted in his contributions to U.S. international broadcasting being largely ignored by those writing about the Voice of America from left-leaning perspectives. The same writers, who have a near monopoly on interpreting VOA’s history, have also been silent on the role of many pro-Soviet American propagandists and journalists in the World War II U.S. government radio broadcasts and the years immediately after the war. At the same time, they downplayed the critical role of refugee and immigrant VOA broadcasters in helping to bring down communism in Eastern Europe. They also vastly overstated the impact of VOA English language news and music broadcasts.

In addition to his technical genius that helped to transform the electronics industry in the twentieth century, Sarnoff, the primary figure behind the development of color television, also had a remarkable understanding of political issues and their impact on business. Even though his formal education was interrupted at a very young age by the need to support his mother and younger siblings (in his younger years, he only completed the eighth grade of elementary school), his immigrant family background, strong religious Jewish faith, intelligence, self-learning, and devotion to science—all contributed to making David Sarnoff a visionary and pioneer in the field of electronics and communications like no other person in America during his lifetime.5 In addition to making correct product development and business decisions, he also acquired an exceptionally prophetic view of international politics. His immigrant experience and, later in life, easy access to influential business and political leaders worldwide helped him to achieve success and fame.

In 1958, Sarnoff was perhaps the only well-known American willing to risk a public prediction that “Within the next 20 years Soviet Communism will collapse under the weight of its economic policies, its political follies, and the pressures of a restive, discontented population.”6 The collapse happened only slightly more than ten years later than Sarnoff had predicted, but even in the 1970s and the early 1980s, almost no one in America believed it would happen soon or in the foreseeable future. He believed new technologies would help pierce the Iron Curtain and “bring home to the Russian people the facts and the truth.”7 He also predicted in 1958 with remarkable foresight that “The Soviet Empire will fall apart as one satellite after another attains its own liberation.”8

It was no coincidence that of all the satellite countries, communism fell first in Poland, the main victim of President Roosevelt’s Yalta policy and his betrayal of the 1941 Atlantic Charter principles, and that it happened during the presidency of Ronald Reagan who, like Sarnoff, also believed in the inevitable and quick dissolution of the Soviet “Evil Empire.” In the 1980s, many left-leaning partisan American-born officials and journalists working for the U.S. Information Agency and the Voice of America viewed Reagan and his “evil empire” speech with contempt. In contrast, many foreign language VOA broadcasters, especially those from communist-ruled nations, were encouraged by his words.9

The betrayed Atlantic Charter guarantees, first agreed to by President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill on August 14, 1941, included free elections and “freedom from fear and want.” They were part of the Four Freedoms announced by President Roosevelt in his State of the Union address to Congress on January 6, 1941: “freedom of speech,” “freedom of worship,” “freedom from want,” and “freedom from fear.” According to Eugene Lyons, it was Sarnoff who had suggested to Roosevelt two of the Four Freedom phrases: “freedom from want” and “freedom from fear.”10

While not alone as a critic of communism among American elites of his time, Sarnoff was in the minority in the media and entertainment industry, whose leading figures and many authors and intellectuals were seduced by Soviet propaganda long before World War II. Before the United States entered the war, Sarnoff tried to interest President Roosevelt and key members of his administration in starting government-funded shortwave radio broadcasts for international audiences in cooperation with private industry. His technical plans for U.S. international broadcasting were implemented in 1942. Still, he was likely discouraged when pro-Soviet American fellow travelers and American and foreign communist sympathizers gained the dominant role in management, program development, and journalism in Roosevelt’s newly-created Office of War Information (OWI).

After the war, Sarnoff advocated for a much stronger countering of Soviet propaganda by the Voice of America and was again at least partially disappointed. However, many of his ideas were used in Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty broadcasts, which he strongly supported. He was an advocate for a free press and freedom of speech. He lobbied to convince the United Nations to establish “Freedom to Listen” as a human right as important as freedom of speech and freedom of the press.11

It is not clear whether his efforts were decisive in this case, but the United Nations’ 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights stated, “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference, and to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media regardless of frontiers.” This would become later the slogan of Radio Free Europe.

Former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who, in her 1949 autobiography, This I Remember, wrote that her late husband “enjoyed his first contact with Stalin” at the “Big Three” Teheran conference in late 1943 and thought that Joseph Stalin’s “control over the people of his country was unquestionably due to their trust in him and their confidence that he had their good at heart,” is usually given credit for being the chair of the UN committee that drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.12 She also wrote that her late husband trusted Stalin when the Soviet leader had told him that the Russians would find themselves “growing nearer to some of your concepts and you may be finding yourselves accepting some of ours” and that he “had a real liking for Marshal Stalin.”13 While representing the United States at the United Nations at the request of President Harry S. Truman, Eleanor Roosevelt indeed had a role in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Still, the concept of defending the right “to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media regardless of frontiers” may have been first proposed to the U.S. government by David Sarnoff.

It is of paramount importance that the principle of “Freedom to Listen” be established. It should be inalienable right of people to listen anywhere and at any time to the voices on the wavelengths that come to them from home and abroad. They have the right to know the truth in the news, and it is the duty of international broadcasting to provide them with the truth.

From David Sarnoff’s address before the United States National Commission for UNESCO, Chicago, Illinois, September 12, 1947

Jewish Family’s Journey from Tsarist Russia to New York

David Sarnoff (1891-1971), the son of Abraham Sarnoff and Leah Privin, was born in Uzlyany (as was Eugene Lyons), a small town near Minsk, then part of the Russian Empire (today part of Belarus). His father was a house painter who left for America in 1896, hoping to find a better life for his family. While he could send some money to his wife, he was having a hard time in New York due to his poor health, and the family’s departure to join him was delayed.

David was an exceptionally bright child and quickly learned to read. On the advice of his maternal grandmother, he was sent at the age of five to his granduncle, a rabbi in a distant town, under whose guidance he memorized Jewish religious texts in Hebrew and Aramaic, sometimes for twelve or fourteen hours a day.14 Finally, after four years, there was enough money for the rest of the Sarnoff family—Leah, David, and his two younger brothers—to journey to America. They arrived in New York on July 2, 1900.15 David was enrolled in a public school and mastered English within a year.16

Young David Sarnoff

Two more children were born to Abraham and Leah in America, but the father’s health continued to deteriorate, and he died soon after David’s sixteenth birthday.17 His father’s illness cut short David’s childhood and made him the family’s main breadwinner at ten and eleven. He started selling Yiddish newspapers, running errands, and doing other chores to help his mother buy food and pay bills.18 He also sang for $1.50 a week in a synagogue choir to contribute to the family budget.19 Still, in his hunger for learning, he found time to attend evening classes at the Educational Alliance, a social institution serving mainly Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe.20

From Office Boy to President of RCA

Young Sarnoff’s first choice in looking for a job at age fifteen was to become a journalist. He went to the New York Herald, looking for any newspaper-related work, but, by chance, the first person he spoke to was a representative of the Commercial Cable Company who offered to hire him as a messenger. Soon, he became more interested in electronic communications, which he realized could also allow him to prosper and improve the lives of people around him and those living abroad. The Commercial Cable Company fired him within a few months when he dared to request leave without pay for the Jewish holidays of Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah so he could sing in the synagogue choir. He quickly found an even better job.21

In 1906, young David Sarnoff started working as an office boy in the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America, running errands for Guglielmo Marconi and discussing radio electronics with the famous Italian inventor.22 In 1909, he advanced to manager at the Marconi station at Sea Gate, Brooklin, and worked as a wireless operator.23 A messenger who later finished an evening electrical engineering course at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, became commercial manager for Radio Corporation of America when the Marconi company was taken over by RCA, general manager and vice-president in 1922, and RCA president in 1930. In 1926, he founded the NBC network, the first national radio network in the United States. Among his many accomplishments, he is credited with developing the television industry in the United States.

Proposes “Voice of America” to Roosevelt

Throughout his business career, various U.S. presidents consulted David Sarnoff on electronic communications issues, and he took such occasions to urge greater U.S. government involvement in international broadcasting. The launch of government radio broadcasts would benefit his company through contracts for equipment purchases. Still, he was also deeply convinced of their urgent need in the world threatened by aggressive propaganda from Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Eugene Lyons noted in Sarnoff’s biography that in the late 1930s and the early 1940s, the president of RCA repeatedly suggested directing broadcasts to foreign countries from the United States. He used the “Voice of America” name in a document in 1943 when U.S. government-produced radio programs were not yet known under that name. At various times, he had talks about international radio broadcasting with President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs Nelson Rockefeller, and FDR’s Secretary of State Cordell Hull.24

In the fall of 1938, Sarnoff discussed the growing importance of international radio with Sumner Welles at President Roosevelt’s suggestion. Sarnoff had talked to Roosevelt earlier about establishing U.S. government shortwave radio broadcasts for foreign audiences, prompting FDR to ask his friend and foreign policy advisor at the State Department to consult with the U.S. radio industry pioneer. Lyons did not confidently claim that Sarnoff had coined the Voice of America name but concluded that “he took the initiative in planting the seed that eventually sprouted as the Voice of America.” 25

In his 1938 memorandum for Sumner Welles, Sarnoff wrote that “mental preparedness” for national defense may prove as vital as military preparedness. He concluded, “Radio, especially in the international field, is the instrumentality by which this can be best accomplished.” 26 At that time, he had no way of knowing that President Roosevelt and the United States government would soon have to embrace Joseph Stalin, a dictator and mass murderer, as an indispensable ally to fight the other dictator and mass murderer, Nazi Germany’s Adolf Hitler.

Comparing “Red Russia” with “Brown Germany”

Even before the start of World War II in September 1939, when Nazi Germany and communist Russia invaded and divided Poland under the secret terms of the Hitler-Stalin Pact (also known as the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact or the Nazi-Soviet Alliance), Sarnoff had been concerned about the growing threat of both Nazi and Soviet communist propaganda. He knew about the pogroms of Jews in Tsarist Russia and was exposed to anti-Semitism and racism in the United States. He developed a distrust of Russia even before the Bolshevik coup after witnessing Cossacks charging on horses against Russians, demonstrating for more freedoms under the Tsar. He recalled that the trampling of women and children “also trampled out of me any lingering feeling I might have had for Russia as my homeland.”27 According to his biographer, Sarnoff would flinch when he later read that someone had described him as Russian-born.28 In Sarnoff’s view, the takeover of the government in 1917 by the Bolsheviks made communist Russia even worse and more threatening to the rest of the world than Tsarist Russia. His 1938 memorandum to Sumner Welles referred to “Red Russia with Brown Germany” in denouncing both totalitarian ideologies.29

Lyons wrote that this comparison of communism with fascism did not endear Sarnoff to those American “intellectuals who were then as ardently pro-Soviet as anti-Nazi.” 30 Some of them would be later in charge of the wartime “Voice of America” broadcasts and would fill them with pro-Stalin propaganda and the whitewashing of Stalin’s genocidal crimes. Besides lionizing Stalin, the Office of War Information also produced propaganda films supporting the internment of American citizens of Japanese ancestry. While not resulting in brutalities and countless deaths, as during the Soviet deportations, this anti-constitutional decision of the FDR administration was modeled after the displacement of entire nationalities and other groups suspected by Stalin of disloyalty toward the communist regime.

Contrary to Sarnoff’s recommendations, Stalin would be presented to Americans by FDR’s propagandists and in Voice of America broadcasts to audiences abroad as a supporter of democracy and liberty and a guarantor of post-war peace and security. FDR based America’s post-war plans on these assumptions about Stalin and Soviet Russia. In line with the President’s wishes and out of their own convictions, Voice of America officials and journalists supported the establishment of communist governments in East-Central Europe. Shortly after the war, a few VOA broadcasters left their jobs in New York and started working as anti-U.S. propagandists or diplomats for Soviet-controlled regimes in Poland and Czechoslovakia.

However, despite FDR’s faith in Stalin, Sarnoff never changed his views about communism. When his biography was published in 1966, Lyons shared Sarnoff’s abhorrence of the Stalinist regime, but his biographer and cousin had not always been a critic of the Soviet Union. Working as a United Press (UP) correspondent in Moscow from 1928 to 1934, Lyons, like many American and British journalists and intellectuals of that period, was initially a fellow traveler of communism and may have been the first Western reporter to be invited for a press interview with Stalin in November 1930. However, Sarnoff’s biography was written long after Lyons lost his enthusiasm for the communist cause and became a critic of Soviet propaganda influence within the U.S. government, including the Voice of America.

David Sarnoff’s WWII Service and Assistance to American Journalists and Radio France

As an immigrant in the United States and someone born in imperial Russia who was aware that Jews were still living in the Soviet Union, prevented from leaving, and arrested on false charges, David Sarnoff knew enough not to be deceived by pro-Soviet propaganda. Still, Eugene Lyons did not find that the president of RCA spoke openly to protect American radio audiences from it during the war with Japan and Nazi Germany when the Soviet Union was America’s military ally. After the United States entered the war, Sarnoff, an Army Signal Corps reserve officer, immediately offered his and his company’s help to the United States armed forces and served as special assistant on communications to General Eisenhower in Europe. Before the June 6, 1944 (D-Day) Normandy landings and the opening of the second front in Europe, Sarnoff proposed the establishment of a mobile Army Signal Center behind the front lines to be made available to journalists covering the invasion.31 Following D-Day, correspondents of American radio networks, including Edward R. Murrow of CBS, expressed their gratitude for Sarnoff’s work in a message to Eisenhower’s headquarters.32

After the liberation of Paris, Sarnoff helped to get Radio France on the air in barely two weeks, including its international short-wave broadcasts.33 Captain Harry C. Butcher, a radio broadcaster who served as the naval aide to General Eisenhower, noted in his memoirs that in October 1944, he saw Colonel Sarnoff smoking a cigar in the lobby of a Paris hotel as he was getting ready to return home having purchased a large selection of lingerie for his family and wearing a U.S. Army Legion of Merit awarded him that day.34 Sarnoff’s wife, Lizette Hermant, was a beautiful French-born Jewish immigrant girl he had met in New York—an “accidental” meeting arranged by their mothers. They fell in love and got married in 1917 after a short engagement. According to his biographer, David Sarnoff explained, “I could speak no French, and Lizette could speak no English, so what else could we do?”35 They were happily married for 54 years.

For his service to France during the war, the French government promoted David Sarnoff to Commander of the Legion of Honor. He had already been a French Legion of Honor officer for several years.36 After President Roosevelt made Sarnoff brigadier general for his U.S. Army war service, his friends, associates, and others often called him “the General.”37 In 1947, President Truman presented him with the Medal of Merit at a White House ceremony.38 Sarnoff maintained good relations with President Truman and supported his policies of containing Soviet aggression in Korea.39

Sarnoff’s relationship with General Eisenhower, whom he greatly admired, was closer than with any other U.S. president, and he became Ike’s friend and advisor. Several years before Eisenhower’s successful run for the White House in 1952, Sarnoff, having heard of the retired general’s financial difficulties, offered him a largely public relations job as RCA president. After considering the offer, Eisenhower politely declined despite a six-figure salary and accepted a less controversial position as president of Columbia University.40 President Eisenhower was weary of the influence of the “military-industrial complex” on U.S. defense and foreign policy and warned about it in his January 1961 farewell address to the nation, but it did not seem to affect his relationship with Sarnoff.

Eisenhower Accuses Voice of America Commentators of “Insubordination”

Sarnoff had likely learned from Eisehower of his profound displeasure with the Office of War Information’s “Voice of America” commentators, whose 1943 broadcast about King Victor Emmanuel of Italy threatened the safety of American soldiers under Ike’s command.

When VOA officials and journalists took their pro-Moscow zeal too far and, in their broadcasts abroad, tried to undermine a critical American diplomatic and military initiative in Italy because communists voiced their objections, President Roosevelt made a rare public statement designed to bring a measure of control over OWI activities and limit foreign propaganda interference in U.S. foreign and information policy. On July 28, 1943, the New York Times published a front-page report by its Washington correspondent and bureau chief Arthur Krock under the headline: “President Rebukes OWI for Broadcast on Regime in Italy.” The President denounced a short-wave “American public opinion” broadcast to Europe by the Office of War Information for calling King Victor Emmanuel of Italy “the moronic little King” and “the Fascist King” and Marshal Badoglio as a “high-ranking Fascist,” Krock reported.41 The New York Times correspondent also noted the OWI’s preference for Soviet propaganda:

The selections of opinions made by the OWI were drawn heavily from purely personal journalistic sources—otherwise undistinguished—which have opposed the President’s Vichy and North African policies and usually produce an “ideology” that conforms much more closely to the Moscow than to the Washington–London line.42

After leaving the White House in 1961, former President Eisenhower briefly alluded in his memoirs Waging Peace (1965) to the Voice of America’s wartime record of collusion with Soviet Russia. As a military leader during World War II, he must have been still upset to have mentioned the incident years later during the Cold War with the Soviet Union when VOA was already playing a useful, although still less than fully adequate, role in countering communist disinformation.

During World War II the Office of War Information had, on two occasions in foreign broadcasts, opposed actions of President Roosevelt; it ridiculed the temporary arrangement with Admiral Darlan in North Africa and that with Marshal Badoglio in Italy. President Roosevelt took prompt action to stop such insubordination.43

Eisenhower also expressed his concerns with what he saw as Voice of America’s unethical journalism supporting partisan political advocacy in one foreign policy incident during his administration.

In Washington I had been told that a representative of the Voice of America (our governmental radio overseas) had tried to obtain from a senator a statement opposing our landing of troops in Lebanon. In a state of some pique I informed Secretary Dulles that this was carrying the policy of “free broadcasting” too far. The Voice of America should, I said, employ truth as a weapon in support of Free World, but it had no mandate or license to seek evidence of lack of domestic support of America’s foreign policies and actions.44

If General Eisenhower had not told Sarnoff in Paris in 1944 about the Voice of America’s “moronic little King” broadcast when he served as his communications advisor and provided assistance to American journalists, he likely read about it in the New York Times or in the former president’s book.

Soviet and Communist Influence at the Office of War Information

Not surprisingly, communists who had turned against Stalin and communism were often the first to expose Soviet influence in the Office of War Information, the wartime parent U.S. government agency of the Voice of America. One of them was Oliver Carlson, a writer, journalist, founder of the Young Communist League of America, and lecturer at the University of Chicago. Carlson, who had never worked for VOA and only observed the organization as an outsider, published a pamphlet, Radio in the Red,” in 1947, describing how pro-Soviet U.S. government propaganda developed with the help of OWI officials and journalists.

During the war years—and largely with government blessing—the Communists moved en masse on the radio, as they did on the movies and the press to help “sell” the American people on the virtues of our Soviet ally. The idea officially projected through such organizations as the O.W.I., was to cure “misunderstanding” of Soviet Russia, which was suddenly discovered to be a “democracy” and a noble social experiment.45

Carlson knew that the Office of War Information produced such propaganda for overseas audiences through the Voice of America and domestic audiences in the United States until Congress eliminated most of OWI’s domestic propaganda budget in 1943. Carlson wrote about domestic OWI propaganda programs, essentially the same as VOA programs.

Tens of millions of radio listeners were deluged with streamlined and dramatic presentations to prove that any talk of Russia as a ruthless dictatorship was a “reactionary” plot. The Bolshevik regime, it turned out, was just a Russian version of our own War for Independence, Lenin a Russian replica of George Washington, Stalin a compendium of Jefferson, Jackson and Lincoln.46 Carlson noted, however, in his 1947 pamphlet, Radio in the Red, published by the Catholic Information Society, that “such crude propaganda, now that the war is over, has declined.” 47

Carlson was not alone in making these observations about the American media’s enthusiasm for the Soviet Union during World War II. Ambassador Charles “Chip” E. Bohlen, who became one of many innocent victims of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s post-war anti-communist witchhunt, which helped Stalin and communists more than anybody else by discrediting all legitimate concerns about their propaganda influence, observed in his memoirs Witness to History 1929-1969, published in 1973, that “The influence of Soviet propaganda on America during the war should not be underestimated.”48 Bohlen was hardly a Soviet sympathizer, as McCarthy alleged, but neither a wild-eye critic of Russia. He acknowledged that some of the American wartime supporters of the Soviet Union “perhaps knew what they were doing and were genuine Party-line boys, eager to capitalize on the situation to promote communism; others were doing it out of general enthusiasm for the war effort and gratitude for the exploits of the Red Army.49 Both of these categories of pro-Soviet officials and journalists, both American and foreign-born, were present in the Office of War Information and the early Voice of America. The number of naive and unwitting Stalin helpers was much larger.

Considering Sarnoff’s earlier recommendations to oppose the totalitarian nature of communism, he could not have been pleased with the pro-Soviet and pro-communist propaganda and disinformation in the wartime VOA broadcasts. Still, Lyons noted that as an Army officer during the war, Sarnoff “necessarily avoided frontal attacks on communism, with which we were then in history’s strangest alliance.”50

Lyons, who at the beginning of his journalistic career had been a Soviet news agency TASS correspondent in the United States, recognized the totalitarian nature of communism much earlier than most fellow travelers and made his break with pro-communist journalists several years before the start of World War II. He was later senior editor of Reader’s Digest and a founding member and the second president of the Overseas Press Club established in New York City in 1939. In the early 1950s, he helped found and was the first president of the American Committee of Liberation (later called the Radio Liberty Committee), which supported Radio Liberty broadcasts from Munich, West Germany to the USSRS, initially, as in the case of Radio Free Europe, with secret U.S. government funding and general oversight by the CIA. David Sarnoff was well aware of his cousin’s pro-Radio Liberty activities, as he himself supported the work of Radio Free Europe.

In his 1937 Assignment in Utopia book, updated and republished in 1967, which described how Lyons and other Western correspondents in Soviet Russia became spokespersons for the Stalinist regime, Lyons noted that American communists and supporters of Stalin were not proletarians, having failed to win the support of American workers, but rather “petty bourgeois and intellectual elements,” for whom “caviar and vodka took the place of the hammer and sickle as emblems of the proletarian revolution” as they attended official Soviet diplomatic functions and “mutual admiration parties thrown by well-to-do Left intellectuals.”51 Some of these Communist Party members and supporters ended up working for the Office of War Information and its “Voice of America” English operation and recruited foreign communists for VOA’s broadcasts in other languages. According to Lyons, Soviet Russia became, for them, a mythical state which had:

“already entered the stage of true socialism,” a Russia of “the world’s most democratic constitution,” the “happy life” and “classless society” that was being entrenched in the American mind. So many weary or bored or panicky Americans had made their spiritual homes in its wonder-chambers that anyone who threatened to undermine its foundations was treated as a shameless vandal. Perhaps he was.52

In another book, Our Secret Allies: The Peoples of Russia, published in 1953, Eugene Lyons wrote about “revivified Stalin worship in the war years when the Kremlin magically became a freedom-loving ally.”53

… the revised legend fashioned by the comrades of the OWI, the BBC, and other Allied agencies celebrated a regime not too different from our own—democratic and liberal in its own inscrutable way. Under the earlier concept the Kremlin was changing the world. In the OWI fairy tales the world was changing the Kremlin. The USSR was now presumably moving closer to our way of life. A hundred experts explained that Soviet Russia was moving closer to capitalism, the capitalist world was moving closer to socialism—and soon the twain would meet and embrace midway.54

It is more than likely that Sarnoff read his cousin’s books about Soviet Russia. After Lyons’s break with communism, their views were remarkably similar. According to Sarnoff’s other biographer, Kenneth Bilby, Lyons, an editor at Reader’s Digest, was also on the RCA payroll as a public relations consultant and drafted Sarnoff’s speeches on the Cold War since the 1950s.55 Bilby wrote that despite their kingship and friendship, after reading the draft, Sarnoff was displeased with Lyons for disclosing some of his personal faults, and their relationship suffered. Sarnoff suggested many revisions, which, according to Bilby, were made, even though the original manuscript was “almost more hagiography than biography.”56

Communist Sympathizers at Early Voice of America

VOA’s chief radio producer, John Houseman, the co-inventor with Orson Welles (no family relation to Sumner Welles) of fake news radio entertainment and the future Hollywood actor, only later declared the first Voice of America director, recruited several Communist Party members and many more Soviet sympathizers for VOA jobs.57 Houseman, who at the time of his appointment in 1942 was not yet a U.S. citizen (he had a British passport) had obtained U.S. citizenship in early 1943 through the special intervention of the OWI deputy director, famous playwright and FDR’s speechwriter and personal friend Robert E. Sherwood.58 However, the State Department still refused to allow Houseman to travel abroad on U.S. government business because of his suspected Soviet and communist links. This information does not appear in Voice of America’s official presentations about its “first director.”

One of Houseman’s protégés, who also does not appear in any of Voice of America’s official presentations of his U.S. government employer’s history or many books and articles about it, was the first chief news writer and editor, Howard Fast, who had worked in his VOA news director position for the Office of War Information until 1944. A best-selling author of historical novels, including Spartacus, which was made into a Hollywood movie, Fast was later a Communist Party USA activist and member of the party’s Daily Worker newspaper editorial staff. In 1953, he received the Stalin Peace Prize, which he accepted with its substantial monetary award and never returned. During the McCarthy period, he was blacklisted and served several months in federal prison, having been convicted of contempt of Congress.

The Roosevelt administration quietly forced Houseman and Fast to resign during the war. However, many pro-Kremlin propagandists among VOA officials and journalists kept their jobs, some of them for several more years.

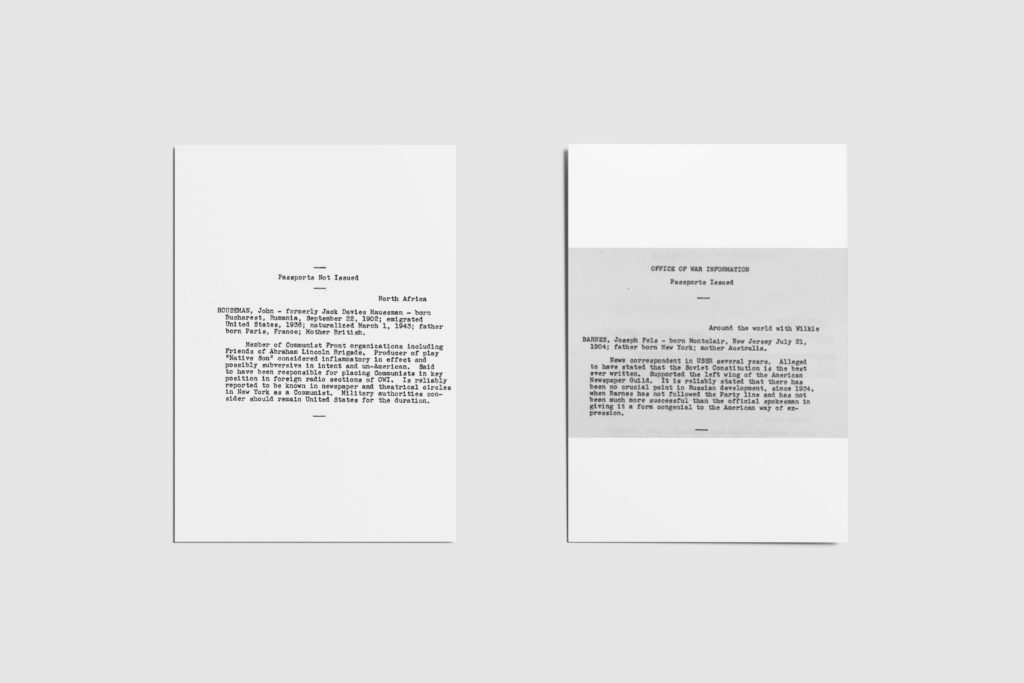

To persuade the OWI leadership to get rid of Houseman, Sumner Welles, and other State Department officials, with the concurrence of the U.S. military intelligence, refused to give him a U.S. passport for official government travel abroad. The then-secret State Department memorandum with warnings about Houseman and other OWI officials sent to the White House in April 1943 contained a few inaccurate accusations, including the claim that a book by African American writer Richard Wright, who later condemned communism, was subversive or that Houseman was a communist (there is no proof that Houseman had joined the Communist Party). Still, most of the information Under Secretary Welles sent to the White House was true. He is best known for the Welles Declaration, which was named after him as its principal author. Issued on July 23, 1940, when he served as the acting Secretary of State, the U.S. government’s statement condemned the June 1940 occupation by the Soviet army of the three Baltic countries—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—and confirmed the United States’ refusal to recognize their annexation into the Soviet Union.

Soviet Disinformation in OWI and VOA Wartime Propaganda

During World War II, the OWI director, former CBS broadcaster Elmer Davis, and OWI and VOA official, journalist Wallace Carroll, spread one of the greatest of Stalin’s propaganda lies to American and foreign audiences. The Soviet dictator falsely claimed he was innocent of the brutal executions of thousands of Polish POW military officers and intellectual, business, and government leaders, collectively known as the Katyn massacre. The Soviets blamed the carnage on the Germans.

Another journalist supporting the Katyn lie was an OWI freelance volunteer in London and Moscow, Kathleen Harriman, the daughter of the U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union. She said after the war that Soviet officials had misled her. When she and her father, Ambassador W. Averell Harriman, were leaving Russia in 1946, Stalin, in his gratitude, presented them with two gift horses.59

Kathleen Harriman’s (Kathleen Mortimer after her marriage) OWI boss in London, Wallace Carroll, who later was a news editor in the Washington bureau of the New York Times (1955-1963) and subsequently editor and publisher of the Winston-Salem Journal and Sentinel, still defended Stalin’s Katyn lie in his 1948 book, Persuade or Perish, designed to teach Americans how to recognize and fight propaganda.60 Yet this spectacular failure to recognize a Soviet deception is strangely omitted from his biography by Mary Llewellyn McNeil, Century’s Witness: The Extraordinary Life of Journalist Wallace Carroll, published in 2022, even though she devotes several pages to discussing his Persuade or Perish book. Century’s Witness jacket includes a quote from Donald Graham, former publisher of the Washington Post, saying, “Only after reading this wonderful book did I understand how great Carroll was. 61 Carroll, like many other progressives of his era, was right about the scourge of racism in America and defended civil rights for all Americans. Still, it does not change the fact he and some others were easily duped by Soviet propaganda and promoted the cult of Stalin with disastrous consequences for millions outside of North America and Western Europe and for Americans who died in the Korean and Vietnam wars, which Stalin and later Soviet leaders had instigated to draw the United States into these conflicts and weaken America’s military and moral power. The Cold War was not only cold. The U.S. government OWI and Voice of America propagandists helped President Roosevelt appease Stalin in ways that could have been avoided, thus making Russia stronger and the United States weaker.

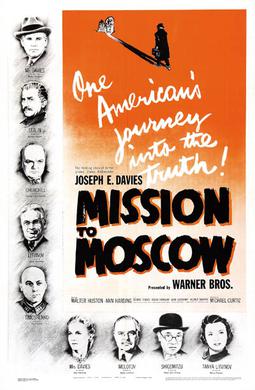

Mission to Moscow Propaganda Film

Many OWI officials besides Carroll and early VOA journalists were engaged in whitewashing Stalin. Media publisher Nelson Poynter, who recommended John Houseman for his VOA position, worked closely in his OWI job with Hollywood’s Warner Brothers on the 1943 Mission to Moscow propaganda film, which presented Stalin as a great statesman who identified and eliminated Fascists and spies trying to kill him and enslave Russia. Directed by Michael Curtiz, the film, based on the highly pro-Kremlin 1941 book by the former ambassador to the Soviet Union, Joseph E. Davies, justified Stalin’s purges and show trials to an even greater extent than Davies—a corporate lawyer, Democratic Party politician, and Roosevelt’s friend—did in a naive analysis in his book. Davies wrote that the show trials and executions were “quite clearly a part of a vigorous and determined effort of the Stalin government to protect itself from not only revolution from within but from attack from without.”62 According to Davies, Stalin got rid of the “Fifth Columnists” engaged in “subversive activities in Russia under a conspiracy agreement with the German and Japanese governments.”63 “The purge,” Davies concluded, “had cleansed the country and rid it of treason.”64 The Mission to Moscow movie took this fantasy conspiracy theory narrative of President Roosevelt’s former ambassador to Russia even further. While Davies served as the U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union from 1936 to 1938, American career diplomats in Moscow, George F. Kennan and Charles E. Bohlen, seriously considered resigning as Foreign Service officers but were dissuaded by their senior colleague, Loy W. Henderson, even though he was also a strong critic of President Roosevelt’s appeasement of Stalin.65

Bohlen did not write in his memoirs that he had thought of resigning but described Davies as “Sublimely ignorant of even the most elementary realities of the Soviet system and of its ideology.” 66 He also observed that in his reporting to the State Department from Moscow, “Davies had relied much more on the opinion of the American press than the judgment of his staff and had spent a lot of time ingratiating himself with American newsmen in Moscow.”67 According to Bohlen, because of his incurable optimism, Davies misled the U.S. government in his reports to Washington.68

George Kennan wrote, “Mr. Davies’s constituents in Moscow—those who received his confidence, and whose opinions he consulted—were not the members of his official staff, they were the American journalists stationed there.69 Two most distinguished American diplomats agreed that many American journalists in the Soviet Union during that period were fellow travelers. One of them was Joseph F. Barnes, the future Voice of America program director in the Office of War Information.

Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles warned the FDR White House about Soviet influence within the U.S. government. His 1943 memorandum had an attachment listing several OWI officials, including Barnes and Houseman:

It is reliably stated that there has been no crucial point in Russian development, since 1934, when Barnes has not followed the Party line and has not been much more successful than the official spokesman in giving it a form congenial to the American way of expression.70

The note about John Houseman attached to Sumner Welles’s memorandum said in part:

Said to have been responsible for placing Communists in key position in foreign radio sections of OWI. Is reliably reported to be known in newspaper and theatrical circles in New York as a Communist. Military authorities consider should remain United States for the duration.71

As one of Roosevelt’s liberal friends, Welles could hardly be accused of being a precursor of Senator Joseph McCarthy, an entire decade before the Republican Senator from Wisconsin started his anti-communist witchhunt, making accusations against some who were Communist Party members and in a few cases Soviet agents, but mostly hurling false accusations against those who were never disloyal to the United States and even those who opposed communism.

Welles’s warnings were not baseless, and, unlike McCarthy in the early 1950s, he was not crusading against liberals and their ideas. He observed in his 1943 memorandum:

If it is desired to give a distinctly liberal cast to these organisations, it would seem possible to find men who are liberal in the light of their own conviction, and of the American ideal, rather than men who have, for one reason or another, elected to give expression to their liberalism primarily by joining Communist front organizations, and apparently sacrificing their independence of thought and action to the direction of a distinctly European movement.72

We know that Welles discussed U.S. international broadcasting issues with David Sarnoff but not whether they talked about Soviet influence within the Office of War Information and its impact on domestic U.S. news media and the film industry. In 1942 and 1943, Houseman was producing “Voice of America” radio programs under the supervision of his boss, Joseph Barnes, and in line with propaganda directives from the OWI deputy director and the head of all OWI overseas operations, Robert E. Sherwood, whose additional job was to coordinate U.S. propaganda with Soviet propaganda and issue program directives to VOA editors. At about the same time, the OWI’s Nelson Poynter reviewed the final script for Mission to Moscow. The U.S. government propaganda agency declared the film “one of the most remarkable pictures of this war” and “a most convincing means of helping Americans understand their Russian allies.”73

Charles Bohlen called the Mission to Moscow movie “one of the most blatantly propagandistic pictures ever screened.”74 According to Bohlen, when Davies showed the film in the Kremlin in 1943, it embarrassed even the Soviet leaders.75

Eugene Lyons described the film, produced with guidance from Nelson Poynter and other OWI officials, as “grotesque” in taking “Stalin-Worship” to new depths.76 More than a decade later, Lyons concluded in a Reader’s Digest article in June 1954 that “Ardent anti-Communists on the inside are now convinced that no known Communists or Communist sympathizers remain.” 77 He also wrote, “Without doubt some ‘subversive’ individuals formerly found their way into VOA, as into other agencies in Government,” but “Fortunately the Voice has cleared house.” 78

Agents of Influence or Spies?

Based on unconfirmed information from others and his own assessment, Lyons strongly suspected some high-ranking OWI officials of being Soviet spies. Still, there was no proof that they were. They were, however, witting or unwitting agents of influence, doing what the Kremlin hoped they would do to protect Stalin’s reputation and advance Soviet interests.

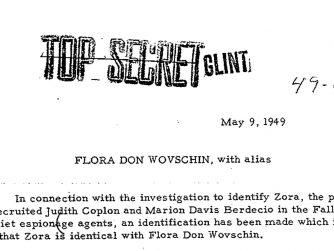

Several actual Soviet intelligence agents in the Office of War Information, including some VOA personnel, were, however, mentioned in cables deciphered under the secret U.S. counterintelligence Venona project. Only one, a young Russian-American communist Flora Don Wovschin (codename “Zora”), a Barnard College graduate whose parents were Communist Party activists, was positively identified by name. Still, the Venona project cables prove there were also others in lower-ranking positions.

Wovschin, who had opposed American aid to Britain during the Hitler-Stalin alliance, transferred from the OWI, where she worked as a research analyst, to the State Department and helped recruit other agents to spy for Moscow. Fearing arrest by the FBI, she defected to the Soviet Union after the war and was reported to have died working as a nurse in North Korea.79

Still, some Voice of America journalists, including at least one former VOA director, are convinced there were never any Soviet spies at the Voice of America and are not reluctant to state it with confidence in public discussions and print.80

Bipartisan Congressional Condemnation of OWI and VOA

On April 13, 1943, Radio Berlin (Reichssender Berlin) broadcast official news of the German Nazi government that German military forces in the Katyn forest near Smolensk, in the then German-occupied region of the Soviet Union, had uncovered a ditch that was “28 meters long and 16 meters wide [92 ft by 52 ft], in which the bodies of 3,000 Polish officers were piled up in 12 layers”. The Germans blamed the murders on the Soviets. The Soviet government blamed it on the Germans— in this case, a blatantly false Soviet accusation designed to cover up the mass murders committed by the secret Soviet police NKVD on the orders of Stalin and the Politburo in April and May 1940.

The Soviet propaganda version of the Katyn Forest massacre was, however, accepted and promoted by the Roosevelt administration, including the Voice of America, despite evidence available to President Roosevelt and the Office of War Information officials who were in charge of overseas VOA broadcasting and domestic U.S. government propaganda that the Soviets were the likely perpetrators of the mass murders. OWI officials, including its director Elmer Davis, repeated Soviet propaganda on Katyn overseas and in domestic broadcasts in the United States. OWI officials, including future U.S. Senator from California Alan Cranston (D), tried to intimidate and censor some American media outlets, most of them Polish American radio stations and newspapers, which attempted to report truthfully to Americans on the Soviet crime.

During April-May 1940, thousands of Polish prisoners of war in Soviet captivity were moved from their internment camps and taken to three execution sites, including the Katyn Forest. The total number of Polish POWs executed by the Soviets in the spring of 1940 is now estimated to be over 20,000. Those who died at Katyn included an admiral, two generals, 24 colonels, 79 lieutenant colonels, 258 majors, 654 captains, 17 naval captains, 3,420 NCOs, seven chaplains, three landowners, a prince, 43 officials, 85 privates, and 131 refugees. Also among the dead were 20 university professors, 300 physicians, several hundred lawyers, engineers, and teachers, and more than 100 writers and journalists, as well as about 200 pilots.81

September 17, 1939, is the date of the invasion of eastern Poland by the Soviet Union under the secret provisions of the Hitler-Stalin Pact, which launched World War II on September 1, 1939. After Hitler betrayed Stalin and Soviet Russia eventually became a major military ally of the United States in the war with Nazi Germany, the Roosevelt administration used the Office of War Information, where radio programs of what would become known later as the Voice of America originated, to hide the origins of the German-Soviet attack on Poland in September 1939 and to help cover up Stalin’s crimes. Many members of the U.S. Congress, however, both during and immediately after World War II, kept warning about the secret collusion between the Roosevelt administration and the Soviet Union.

Close cooperation between Soviet and American government propagandists and employment of Soviet agents of influence at the wartime Voice of America helped to obscure the betrayal of U.S. allies and democratic values at the February 1945 Yalta Conference between President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. The appeasement of Stalin was accompanied by the U.S. government’s pro-Russian propaganda and censorship of information to prevent Americans and foreign audiences from learning about the true nature of Soviet communism and Stalin’s intentions to subjugate Central and Eastern Europe. While protecting Stalin and Russia from criticism was excused by some during the war as dictated by military necessity, it was harder to excuse the continuing coverup of Stalinist crimes in the immediate post-war Voice of America broadcasts until President Truman took action to remove pro-Soviet officials and broadcasters and his Democratic administration hired anti-communist refugee journalists from Eastern Europe. But for some Democrats, it became, for many decades, a partisan coverup to protect the reputation of President Roosevelt and the Democratic Party. For some, it was also an ideological refusal to abandon their attachment to radical socialist ideas, the coverup to hide their mistakes, and the embarrassment of being duped by Soviet propaganda. Ironically, the reluctance to expose and admit FDR’s and the Office of War Information’s and Voice of America’s mistakes was much lesser among members of Congress of both parties, including Democrats, than among left-leaning intellectuals, academics, and journalists. Some of the strongest critics of the pro-Soviet line in Voice of America broadcasts during and shortly after the war were non-racist, progressive northern Democrats supported by labor unions and various ethnic communities.

After the war, one of many members of the U.S. Congress who raised the alarm about Soviet influence and censorship at the Voice of America was a U.S. Representative from Illinois (1951 to 1959), Timothy P. Sheehan. He was a moderate Republican member of the bipartisan Select Committee of the House of Representatives investigating the 1940 Soviet mass murder of Polish officers in the Katyn Forest near Smolensk, Russia. In a supplementary statement to the committee’s Final Report, Congressman Sheehan included a segment on “Propaganda Agencies.” The congressional investigation put a stop to most of VOA’s censorship of the Soviet responsibility for executions in Katyn and in other locations, in which the NKVD secret police shot more than 20,000 Polish military officers and government leaders.

The Select Committee of the House of Representatives, which investigated the Katyn Massacre, is also known as the Madden Committee after its chairman, Rep. Ray Madden (D-Indiana).

Rep. Timothy P. Sheehan observed in his separate statement in the bipartisan Madden Committee’s Final Report:

Admittedly, during the Katyn investigation, we but scratched the surface on the part that the Office of War Information and the Voice of America took in following the administration line in suppressing the facts about the Katyn massacre. During the war there may have been a reasonable excuse for not broadcasting facts which were available in our State Department and Army Intelligence about the Katyn massacre and other facts which proved Russia’s failure to live up to her agreements. After the war there certainly was no excuse for not using in our propaganda war the truths which were in the files of our various Government departments.

One of the witnesses from the Department of State, which controls the policy of the Voice of America, stated that they did not broadcast the fact of Katyn behind the iron curtain was because they did not have sufficient facts on it. Yet the preponderance of evidence presented to our committee about the cover-up came from the files of the State Department itself.

The Voice of America, in its limited broadcasts about the Katyn massacre, followed a wishy-washy, spineless policy. From other information revealed about the policies followed by the Voice of America, a committee of the Congress ought to make a thorough investigation and see to it that the Voice pursues a firm and workable propaganda program and does not serve to cover up the mistakes of the State Department or the incumbent administration.82

In the “Misjudgment of Russia” section, Congressman Sheehan also mentioned the Voice of America’s role in misleading foreign and American public opinion. During World War II, many of the Office of War Information news and broadcasts were widely distributed to media in the United States. The U.S. Congress put a legal stop to the domestic distribution of VOA programs by passing the 1948 Smith-Mundt Act. However, the primary purpose of the Smith-Mundt Act was to authorize the U.S. government’s information programs abroad.

The Final Report of the Madden Committee was issued on December 22, 1952. Democratic and Republican committee members concluded that Office of War Information officials in the Roosevelt administration engaged in illegal censorship of U.S. domestic media during the war, targeting Polish American radio stations that broadcast accurate information about the Katyn massacre and other Soviet atrocities.

OFFICE OF WAR INFORMATION, FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION

When the Nazis, on April 13, 1943, announced to the world the finding of the mass graves of the Polish officers at Katyn and accused the Soviets, the Allies were stunned by this action and called it propaganda. Mr. Elmer Davis, news commentator, then head of the Office of War Information, an agency established by Executive order, told this committee he reported direct to the President. Under questioning he admitted frequent conferences with the State Department and other Government agencies. However, testifying before this committee, when faced with his own broadcast of May 3, 1943, in which he accused the Nazis of using the Katyn massacre as propaganda, he admitted under questioning that this broadcast was made on his own initiative.

This is another example of the failure to coordinate between Government agencies. A State Department memorandum dated April 22, 1943, which was read into the record (see vol. VII of the published hearings), stated:

and on the basis of the various conflicting contentions [concerning Katyn] of all parties concerned, it would appear to be advisable to refrain from taking any definite stand in regard to this question.

Mr. Davis, therefore, bears the responsibility for accepting the Soviet propaganda version of the Katyn massacre without full investigation. A very simple check with either Army Intelligence (G- 2) or the State Department would have revealed that the Katyn massacre issue was extremely controversial.

Furthermore, members of the staff of both OWI and FCC did engage in activities beyond the scope of their responsibilities. This unusual activity of silencing radio commentators first came to light in August 1943 when the House committee investigating the National Communications Commission discovered the procedure.

The technique utilized by staff members of OWI and FCC to silence was as follows: Polish radio commentators in Detroit and Buffalo broadcasting in foreign languages after the announcement of the discovery of the mass graves of Polish officers at Katyn reported facts indicating that the Soviets might be guilty of this massacre.

In May 1943 a member of the FCC staff suggested to a member of the OWI staff that the only way to prevent these comments was to contact the Wartime Foreign Language Radio Control Committee. This committee was made up of station owners and managers who were endeavoring to cooperate with the OWI and FCC during the war years. Accordingly a meeting was arranged in New York with two of the members of this industry committee. They were specifically requested by the OWI staff member to arrange to have a Polish radio commentator in Detroit restrict his comments to straight news items concerning Katyn, and only those by the standard wire services. The fact that a member of the FCC staff attended this meeting is significant because the FCC in such a case had no jurisdiction. In fact, the FCC member was in New York to discuss the renewal of the radio license of one of these industry members. The owner of the radio station in Detroit was contacted and requested to restrict the comments of the Polish commentator on his station, and this was done.

By applying indirect pressure on the station owner, these staff members accomplished their purpose, namely, keeping the full facts of the Katyn massacre story from the American people. (See vol. VII of the published hearings.)

Office of Censorship officials testified and supported the conclusion of this committee that the OWI and FCC officials acted beyond the scope of their official Government responsibilities on this matter of Katyn. Testimony before this committee likewise proves that the Voice of America—successor to the Office of War Information—had failed to fully utilize available information concerning the Katyn massacre until the creation of this committee in 1951. The committee was not impressed with statements that publication of facts concerning this crime, prior to 1951, would lead to an ill-fated uprising in Poland. Neither was it convinced by the statements of OWI officials that for the Polish-Americans to hear or read about the Katyn massacre in 1943 would have resulted in a lessening of their cooperation in the Allied war effort.83

1932 Pulitzer Prize for Walter Duranty Defended in 2003

Many elite White American and British journalists supported the Soviet experiment with communism and whitewashed Stalin’s acts of genocide. Sarnoff’s cousin, Eugene Lyons, was initially one of them until the publication in 1937 of his best-selling book, Assignment in Utopia, in which he described Soviet Russia as it truly was and admitted his part in spreading pro-Stalin disinformation.

Once he gave up his allegiance to communist dogma and was outside of the Soviet Union, Lyons wrote about thousands of homeless children roaming through the Russian countryside in search of food. Their “kulak” peasants, he pointed out, had died from starvation or allowed them to escape before being herded in cattle trains, taking them into exile to slave labor camps, where they were discarded without adequate food and shelter. He wrote about the peasants from liquidated Ukrainian villages who were hardly prosperous “kulaks,” as presented in Soviet propaganda posters. “I saw batches of the victims at provincial railroad points under G.P.U. guards, like bewildered animals, staring vacantly into space,” the journalist told American readers.84 He then described in Assignment in Utopia how most Western journalists in Moscow, including himself, had reported on “the liquidation of the kulaks as a class”:

For a few correspondents it provided a useful opportunity to demonstrate their “friendship” and “loyalty” for the Soviet regime by explaining away ugly facts, wrapping them in the cellophane of Marxist verbiage, slurring over them with cynical allusions to broken eggs for Soviet omeletts. Others were curbed by the censorship, and grateful enough on occasion for this convenient alibi for silence.85

“Broken eggs for Soviet omelets” referred to the expression used by Walter Duranty, the Anglo-American New York Times reporter in the Soviet Union in the 1930s who worked for the Times until 1941.86 In his report from Moscow in March of 1933 titled, “Russians Hungry But Not Starving,” Duranty described the “mess” of collectivization. “But – to put it brutally – you can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs.”87

Duranty received the Pulitzer Prize for his earlier reporting from Soviet Russia. The New York Times eventually published a weak admission that “Times correspondents and others have since largely discredited his coverage.” It noted that “Since the 1980s, the paper has been publicly acknowledging his failures.”88 However, the Pulitzer Prize Board has declined to withdraw the award for Duranty, stating in November 2003 that there was “no clear and convincing evidence of deliberate deception” in his earlier 1931 reporting, for which he had won the prize.89 The 2002-2003 Pulitzer Prize Board membership reads like a Who’s Who of the American media, academia, and intellectual establishment.90 These men and women of the Pulitzer Prize Board would have most likely never thought twice about revoking the journalism prize if it were discovered that the winner had supported fascism and Hitler.