By Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

Soviet influence at Voice of America during World War II — documents and analysis

Soviet influence at WWII Voice of America

From VOA to communist regime journalist

Choices of VOA’s pro-Soviet journalist

VOA journalist marries Communists

A pro-Soviet propagandist at OWI and VOA

VOA communist partner Stefan Arski

Pro-Soviet collaborators at OWI and VOA

A VOA friend of Stalin Peace Prize winner

Among Soviet sympathizers at VOA

Critics of her communist influence at VOA

Was she VOA’s communist ‘Mata Hari’?

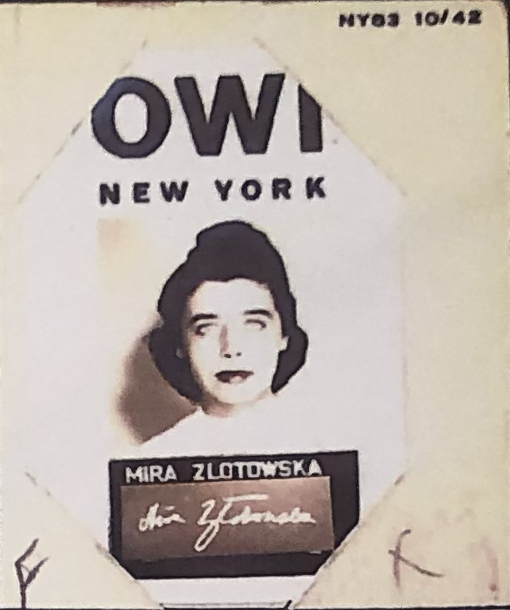

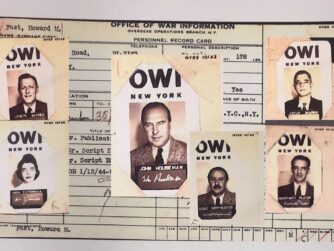

Mira Złotowska, later known as Mira Michałowska who published books and articles in English as Mira Michal and used several other pen names, was one of many radically left-wing journalists who during World War II worked in New York on Voice of America (VOA) U.S. government anti-Nazi radio broadcasts but also helping to spread Soviet propaganda and censoring news about Stalin’s atrocities. While not the most important among pro-Soviet propagandists at the Voice of America during the war, Michałowska later went back to Poland, married a high-level communist diplomat and for many years supported the regime in Warsaw with soft propaganda in the West while also helping to expose Polish readers to American culture through her magazine articles and translations of American authors. One of the American writers she translated was her former VOA colleague and friend, the 1953 Stalin Peace Prize winner Howard Fast who in 1943 played an important role as VOA’s chief news writer. Despite today’s Russian attempts to undermine journalism with disinformation, the Voice of America has never officially acknowledged its mistakes in allowing pro-Soviet propagandists to take control of its programs for several years during World War II. Eventually, under pressure from congressional and other critics, the Voice of America was reformed in the early 1950s and made a contribution to the fall of communism in East-Central Europe.

Marriage to Złotowski, a suspected spy

In the 1930s, Mira Zandel whose last married name was Mira Michałowska studied journalism in Warsaw for one year after getting her high school diploma, known in Polish as matura. She married a Polish nuclear physicist and chemist, Ignacy Złotowski who in the 1930s collaborated with double Nobel Prize winner Madame Marie Curie Skłodowska and, after her death, with her daughter Irene, at the Radium Institute in Paris. He also collaborated with Nobel Prize winner Jean Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie at Laboratory of Nuclear Chemistry at Collège de France. While they were married, Mira Złotowska continued her university studies in Paris. Her husband was sometimes identified in congressional and other American documents as Ignace Złotowski. His scientific collaborators, Jean Frédéric Joliot-Curie, was a prominent member of the French Communist Party and was known to have passed to the Soviets the information he had received about British and American nuclear weapons program. Joliot-Curie was the recipient of the first Stalin Peace Prize, given in 1951. As a foretaste of their later political choices, Ignacy Złotowski and his wife were already moving in communist circles, first in France and later in the United States.

Złotowska and her husband emigrated to America through Casablanca and Lisbon after the German occupation of France. She noted on her OWI job application that she had arrived in New York on November 11, 1940. They may have celebrated her 26th birthday together in the United States, but she and Złotowski would go eventually their separate ways, although it is not known when exactly their marriage and relationship had ended. Professor Złotowski found work as a research assistant at the University of Minnesota School of Chemistry in Minneapolis, was an assistant professor at Vassar College and later a professor at the University of Ohio from July 1944 to January 1, 1946. He returned to Poland in 1946 and was appointed as the chief of the American Section in the Foreign Ministry in the communist-dominated government. He was sent back to the United States in October 1946 as an alternate delegate for the United Nations General Assembly session. It was then that he was tainted with accusations of engaging in atomic espionage.

A high-level Polish defector, General Izydor Modelski, a former military attaché at the communist regime’s embassy in Washington, testified in April 1949 before the House Subcommittee on Un-American Activities that he became convinced Professor Złotowski, who may or may not have been still Mira Złotowska’s husband, was in charge of the Warsaw regime’s intelligence unit attempting to acquire in 1946 atomic information in the United States. General Modelski, who was a highly respected military officer in the Polish Army before the war and fought against the Soviets in the 1920 war and opposed the 1926 military coup in Poland, told the House subcommittee that he had informed the United States intelligence service that Złotowski “is a Communist,” that “he is a scientist” and that his visit to the United States “is not a diplomatic trip.” Modelski, who immediately after his arrival in the United States in 1946 started to cooperate secretly with the U.S. intelligence service, said he was quite sure Złotowski was a spy, but he did not know whether any intelligence information gathered by him was passed directly to Poland or to Russia. He speculated that it could have been sent both to Warsaw and to Moscow. U.S. atomic program secrets would have been far more useful to Russia than they would be to Poland which was never going to have atomic weapons.

How much Mira Złotowska knew about her husband’s or ex-husband’s alleged spying activities in the United States, or if she knew about them at all, cannot be determined from any documents I have seen. In another congressional testimony, which he gave in May 1949 before the Senate Subcommittee on Immigration and Naturalization of the Judiciary Committee, General Modelski described Professor Złotowski as “a prominent Communist” and “a great scientist” who in 1946 became deputy to Polish communist ambassador in Washington Professor Oskar Lange, a know KGB asset. [ref]After the war, Ignacy Złotowski was a university professor in Poland highly valued for his work by the communist authorities. An article inserted into the Congressional Record in 1968 alleged that as a nuclear scientist, Złotowski participated in Soviet atomic espionage in the United States. I found no records to prove it. We know that his wife or ex-wife was in contact with a known Soviet intelligence agent in the United States, Bolesław (Bill) Gebert, but Soviet diplomatic cables deciphered under the Venona project do not identify Złotowski as a spy.[/ref]

I could not find the record of Mira Złotowska’s eventual divorce from her scientist husband, but she lived in New York when on October 17, 1942 she was hired by the Office of War Information as an assistant script editor (Polish) while her husband worked in Minnesota.

What became known later and may have contributed to spying accusations being made against Mira Złotowska were her contacts in the United States during and after World War II with two individuals whom the KGB regarded as trusted collaborators. One of them was an intelligence agent and another an important agent of influence. These contacts could have been related to her job as a journalist at the Voice of America or could have been driven by her desire to see a pro-Moscow socialist government being established in Poland after the war, or most likely both. There is no documentary evidence that Mira Złotowska had spied for the Soviet Union at that time or later. She was, however, publicly accused in articles published in the United States in the late 1960s of spying on Americans when after the war she was the wife of the Polish communist regime’s ambassador, Jerzy Michałowski, first in London (1946-1953) and later in New York at the U.N. (1956-1960) and at the embassy in Washington (1967-1972). According to the Polish Wikipedia article, she and Michałowski were married in 1947, but there is no specific citation exactly when and where.

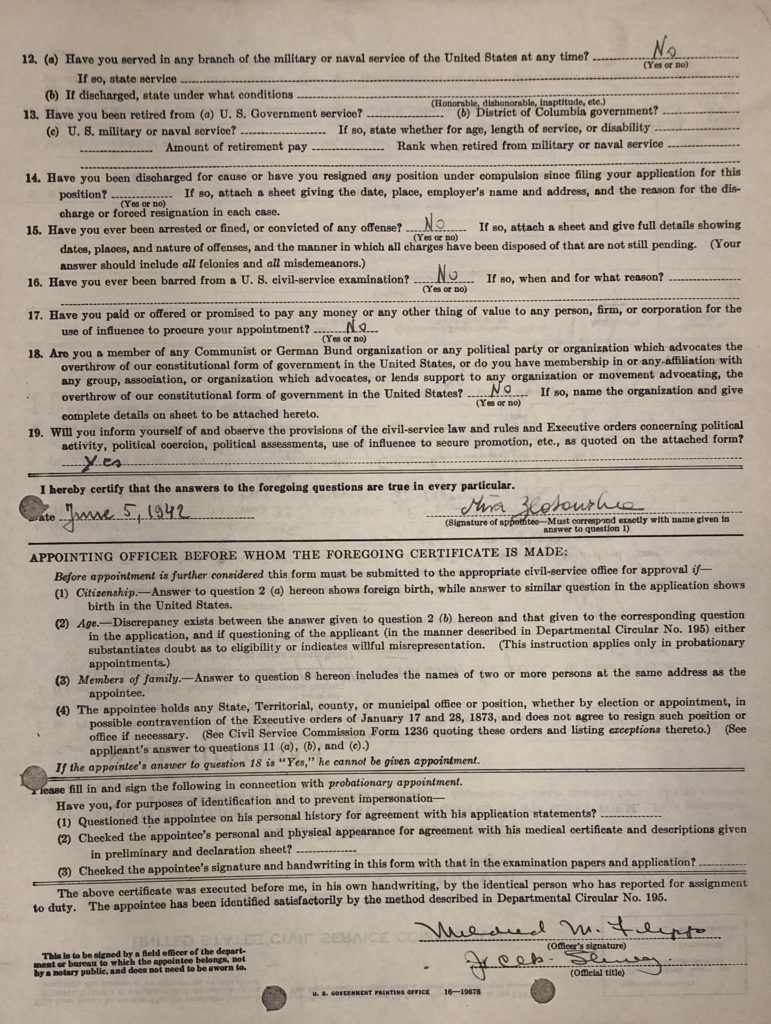

Reported arrest for communist ties

Mira Złotowska’s archived personnel records show that she apparently lied on her U.S. government job application by responding “No” to the question whether she had ever been arrested. According to a detailed biographical article about her in Polish Wikipedia, she was arrested in Poland in 1935 under suspicion of collaborating with a Communist Party newspaper, but this information lacks a specific citation. The Polish Communist Party was at that time illegal in Poland after it supported the Soviet attack on the country in 1920 and was regarded by the vast majority of Poles as a subversive organization taking orders from Soviet Russia. The investigation of her alleged communist ties was terminated after a few months, and she was released from jail without being charged in Poland with any crime. In a twist of historical irony, Stalin ordered the pre-war Communist Party of Poland to be dissolved in 1938 after having many of its leaders who lived in exile in the Soviet Union arrested, tried and executed on various false treason and espionage charges. The post-war Polish Communist Party, which governed the Polish People’s Republic from 1948 to 1989, was called the Polish United Workers’ Party.

Zenon Kliszko

Mira Michałowska’s biographical entry on the Association of Polish Writers website also mentions her marriage to a Communist Party activist Zenon Kliszko before her marriage to Ambassador Michałowski. Rumors of her marriage to Kliszko, which could have been her first marriage, but for which I have not yet seen a definite documentary proof, show that she was regarded as well-connected with the post-war communist elite in Poland, in which Kliszko played a key role. According to one Polish media article, she supposedly rescued Kliszko from prison in pre-war Poland by producing a fake doctor’s certificate that he had a mental impairment, but her family doubts that she and Kliszko were ever married.[ref]Piotr Oczko, “Wybór Miry. O Mirze Michałowskiej, Miesięcznik Znak, nr 769, June 2019.[/ref] Still, her links with high-level Communist Party leaders made her a sought after figure for Western diplomats and journalists looking for information about the communist system and for access to its various officials, which could explain how accusations of spying might have originated. Kliszko was a high-ranking Polish Communist Party activist who was also arrested during the Stalinist period but after 1956 became the right-hand man to the Party’s First Secretary and de facto the country’s communist ruler Władysław Gomułka.

When Gomułka came to power after the 1956 anti-regime demonstrations and was regarded at first as a communist reformer wanting more independence from the Soviet Union, Złotowska and Kliszko were no longer in a close relationship if such a relationship existed. Kliszko was a typical example of a right-wing communist ideologue.

Anti-Semitism

Many years later, Zenon Kliszko was blamed for the regime’s decisions which led to student protests in 1968 and the forced exodus from Poland of many Polish Jews, including artists, intellectuals and some party and government officials. The Polish Communist Party and the communist government turned out to be spectacularly right-wing after all in its treatment of Jews, just as the regime was repressively right-wing from the very beginning in treating all political opponents. Kliszko was also blamed for the decision to open fire on striking Polish workers in 1970. He was eventually fired from his job and expelled from the Communist Party by the new party leader, Edward Gierek.

In an article published in Poland in June 2019, a Polish scholar suggested that Mira Michałowska and her diplomat-husband became belated victims of the anti-Semitic Communist Party purge when Jerzy Michałowski after retiring from diplomatic service in 1971 was, according to the author, removed from the Party ranks and his wife was banned for several years from traveling abroad because she reportedly, at least at that time, refused to provide the regime’s intelligence service with reports about her foreign contacts. The article does not specify how or from whom this information was obtained, but it is believed to have come from the surviving members of her family.[ref]Piotr Oczko, “Wybór Miry. O Mirze Michałowskiej,” Miesięcznik Znak, nr 769, June 2019.[/ref]

Life of privilege

Whatever may have caused Mira Michałowska eventually to privately dislike the regime, she may have done well for her journalistic and writing career by her links with the Communist Party elite in Poland and by marrying one of its ambassadors, as well as by her earlier decision to leave her job as an editor of propaganda materials for the U.S. government and to return to Poland after the war. If she had to live in Poland, this former Voice of America journalist, as a wife of a key regime diplomat, was able to travel abroad and live in the West instead of spending most of her time under the grim material realities of life under communism.

Even if she had married a party apparatchik like Kliszko who would not have been able to travel frequently to the West, as a member of the party aristocracy even her life in Poland would have been, and it was when she was there, still incomparably better than for the majority of ordinary Poles. Living in London, New York and Washington, DC in the 1950s and the 1960s put her in touch with many influential individuals and celebrities and was good for her writing career. She seemed to take full advantage of the many privileges and perks reserved for the ruling elite in Poland and by all accounts tried to help the regime develop a better and gentler image in the West, just as she was helping to consolidate its power in Poland at the end of the war when she worked on Voice of America broadcasts and for Time and Harper’s magazines in the 1940s.

While I found no evidence that Michałowska had supported political violence and repressions, she was permanently loyal to the regime that used intimidation and force well into the 1980s.

After their return to Poland, Mira Michałowska‘s former Voice of America colleague and friend Stefan Arski frequently condemned former anti-Nazi Polish fighters who opposed the regime and refugees in the West who fought against Hitler’s armies as being Fascists and American spies. Michałowska to the best of my knowledge did not use such language. She had far more class and grace. Her defense for first supporting and then continuing her writing and translating career under the regime which censored many Polish and foreign writers might have been that the Soviets were ultimately responsible for the suppression of freedom in Poland. She would probably claim that progressive left-wing journalists and writers like herself who chose to support the new order rather than to oppose it openly were in their own way helping the Polish people live better and safer lives by bringing Poland slightly closer to the West within the limits imposed by the Soviet Union and the top leadership of the Communist Party. In addition to writing books and articles, she also translated into Polish books of several American authors, including Ernest Hemingway, Sylvia Plath, E.L. Doctorow, Saul Bellow, Anaïs Nin, Joan Didion, Gore Vidal, Jerzy Kosiński and a few others. She brought America closer to Polish readers living under communism while also helping to keep the regime in place but perhaps trying to give it a more human face. It is the best defense that can be made.

For most Poles, who had rebelled again and again against communism, such attempts to reform it from within by the regime’s supporters among writers and artists, were not enough. Opponents of communism realized that there were millions of them when Pope John Paul II made his first visit to Poland in 1979. At that point, the regime was already doomed to fall as soon as the Soviets lost their will to invade Poland to keep it in power. The regime could not survive on its own. Many of the left-leaning intellectuals who initially supported the communist system eventually became activists in the anti-communist opposition. Mira Michałowska did not appear in that group. To my knowledge, she never issued any public apologies for her earlier propaganda work in America at the Office of War Information in support of communism in Poland.

Ted Lipien was Voice of America acting associate director in charge of central news programs before his retirement in 2006. In the 1970s, he worked as a broadcaster in the VOA Polish Service and was the service chief and foreign correspondent in the 1980s during Solidarity’s struggle for democracy in Poland.