As Vladimir Putin and his propagandists intensify their campaign to falsify history and interfere in U.S. elections, it is helpful to remember that such Russian attempts to present lies to influence American politics and media are not new. Americans, including top political leaders and journalists, had been previously deceived on a much more massive scale by propaganda from the Kremlin. During World War II, Joseph Stalin received help from many quarters in spreading his disinformation lies and propaganda attacks. His “useful idiots” included the Communist Party USA and many ideologically motivated, usually unwitting agents of influence. Some were working for the U.S. government, including those who had prepared Voice of America World War II radio programs for foreign audiences and the Office of War Information propaganda materials targeting Americans and American media.

Soviet leaders were exploiting social problems and conflicts in American society for propaganda purposes in the same way Russian propagandists exploit problems and conflicts today to the advantage of President Putin and his government. They skillfully use disinformation to divide and confuse Americans, targeting journalists, political leaders, experts, academics, and a variety of extremist groups.

The success of Soviet and communist propaganda in deceiving many American leaders and many journalists during World War II and even for a few more years after the war was nothing short of phenomenal and affected especially the U.S. government’s own propaganda agency and its early Voice of America radio broadcasts.

The manipulation and subversion of American politics and institutions by Soviet propaganda is a historical fact that, unfortunately, has been largely obscured and forgotten. The Voice American management today still does not admit that VOA in its early years had employed many Soviet sympathizers. Such unwillingness to acknowledge past mistakes and to learn from them–combined with generally poor knowledge of history among Americans–makes it harder for today’s journalists to understand how Putin conducts his propaganda warfare and how to respond to it effectively.

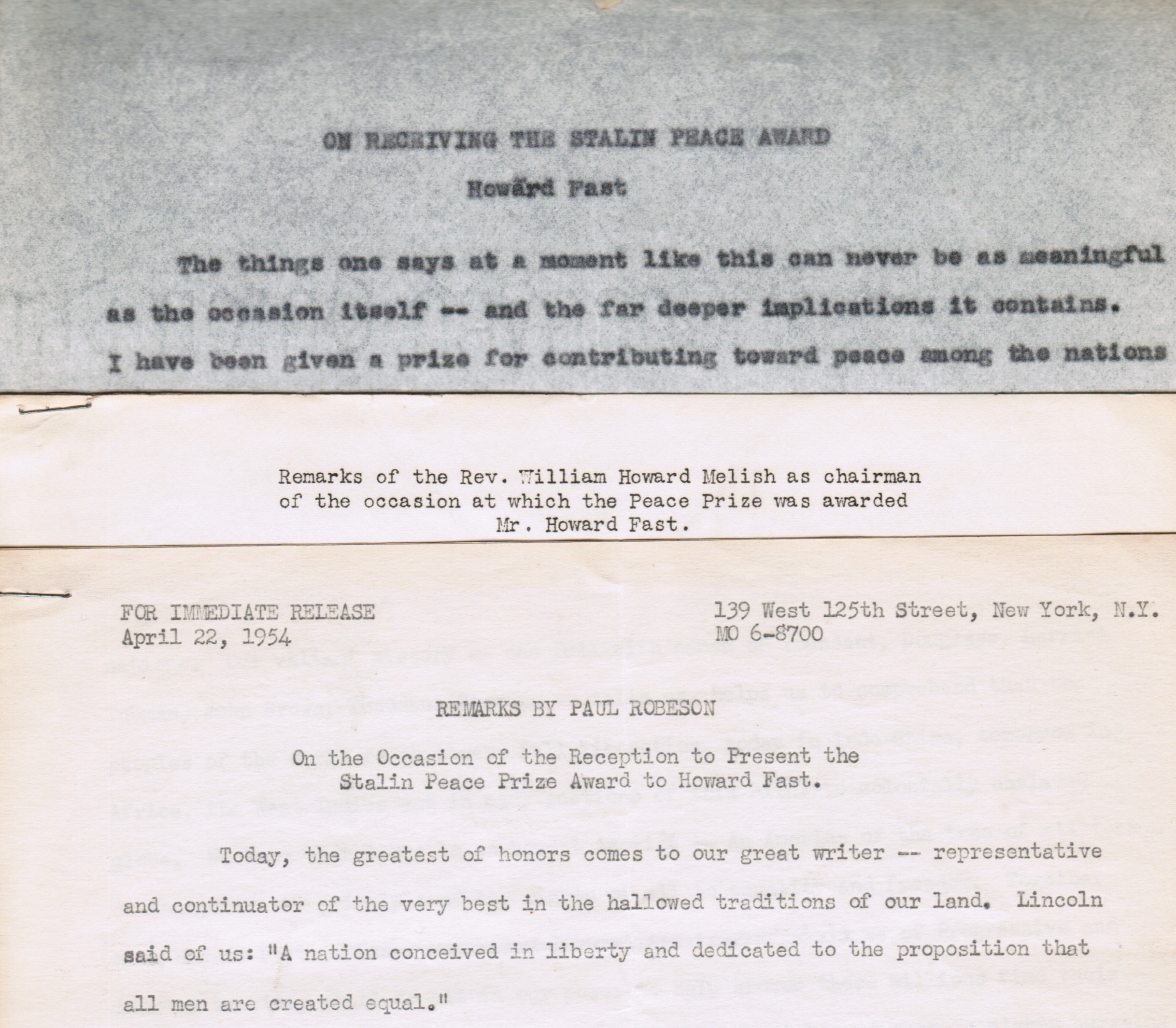

The Cold War Radio Museum has acquired recently original documents with texts of speeches delivered in New York on April 22, 1954 at the ceremony during which former Voice of America chief wartime (1943) writer and editor Howard Fast (1914-2003) received his 1953 Stalin International Peace Prize. The peace offensive played a key role in Soviet propaganda and disinformation campaigns of the Cold War era. In his speech, Fast repeated many of the Soviet propaganda slogans, few of which were even remotely true.

Howard Fast’s four-page, onion-skin paper, carbon copy speech has a worn first page, other pages mildly yellowed with one emendation in pencil on the first page.

The original documents also include two mimeographed pages of remarks by Rev. William Howard Melish, with penciled speaker’s notes on the verso of the last page. He was one of the honored guests at the 1954 New York event. Another special guest was African-American actor and singer Paul Robeson. Like Fast, Robeson was also a Communist Party USA member. He had received the Stalin Prize the preceding year.

A two-page press release of Robeson’s comments is mimeographed, with a fold crease and some yellowing, a small chip at the center fold, and ink jotting on the verso of the last page.

At the time when the Soviet regime was still enslaving millions of people, Fast praised the Soviet Union in his 1954 speech for defending world peace:

This prize, awarded to me and to many others by an international jury, originates in the Soviet Union. If I had no other cause for honoring the Soviet Union, I would honor it greatly and profoundly for giving prizes for peace.

In his speech during the ceremony in honor of Howard Fast, Paul Robeson praised Joseph Stalin who died a year earlier, in March 1953:

This is the Stalin Peace Prize — given in the name of one of the greatest leaders of the Peoples of the Soviet Socialist Republics and of all human kind. Stalin understood profoundly the meaning of equality among nations and the unbreakable unity of these Soviet Socialist Republics with the New China, with the New Peoples Democracies does honor to his memory.

By that time, Stalin and the leaders of China and other communist states were already responsible for the murder of millions of people.

Fast, who at times claimed to be a journalist, should have known these facts.

Robeson, who had experienced severe racism in America, was a far more tragic figure of the two and could have had an excuse for bitterness toward American capitalistic democracy, but he also remained a true believer in communism and the Soviet Union long after Stalin was exposed as a mass murderer.

Both Robeson and Fast later left the Communist Party. Fast’s daughter, Rachel Fast Ben-Avi, wrote that after Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev detailed Stalin’s atrocities, her father resigned from the Communist Party “immediately, loudly, publicly.”[ref]Fast Ben-Avi, Rachel. “A Memoir” in Red Diapers: Growing Up in the Communist Left, edited by Judy Kaplan and Linn Shapiro (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 133.[/ref]

But neither Fast nor Robeson condemned communism, the Soviet Union, and the new leaders in the Kremlin. In 1956, Robeson expressed his support for the Soviet invasion of Hungary.

At the 1954 ceremony in New York, Rev. William Howard Melish, a pro-Kremlin American peace activist who frequently traveled to Russia, praised Fast and Citizen Tom Paine, one of Fast’s early books.

Fast could not receive his Stalin Peace Prize in Moscow in 1953 because the State Department refused to provide him with a U.S. passport.

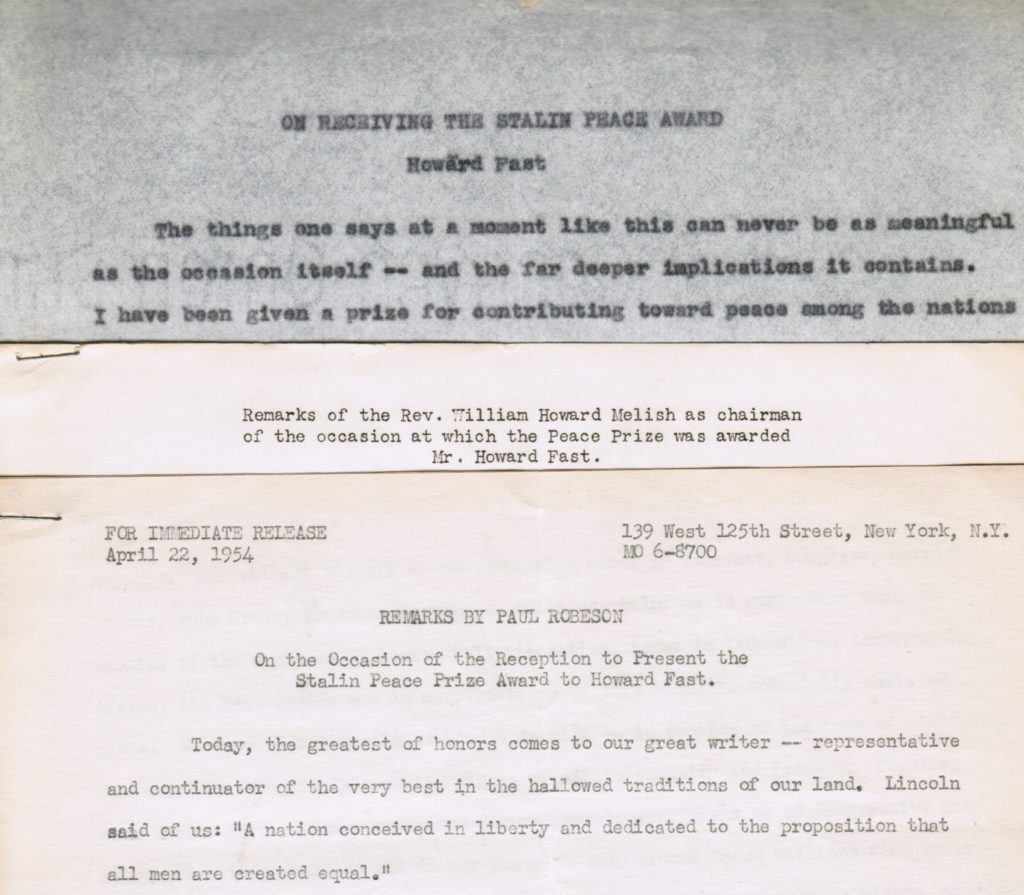

In 1954, Fast was no longer a U.S. federal government employee, but ten years earlier he was an important figure among journalists and broadcasters at the U.S. Office of War Information. During World War II, pro-Soviet fellow travelers and communist sympathizers were put in charge of the U.S. government’s domestic and foreign propaganda. Howard Fast was the chief writer and editor of Voice of America radio broadcasts in 1943.

After leaving VOA in January 1944 under some pressure from the U.S. State Department but still highly-regarded by his OWI bosses, Fast became a card-carrying member of the Communist Party USA and was a reporter and editor of the party’s newspaper. In addition to his political and journalistic activities in support of communism and the Soviet Union, Howard Fast was also a talented and prodigious author of bestselling historical novels, including Spartacus, which was made into a popular Hollywood movie.

While working at the Voice of America, Howard Fast admitted to using his Soviet Embassy contacts as news sources while rejecting negative information about Stalin as anti-Soviet propaganda.

I established contact at the Soviet embassy with people who spoke English and were willing to feed me important bits and pieces from their side of the wire. I had long ago, somewhat facetiously, suggested ‘Yankee Doodle’ as our musical signal, and now that silly little jingle was a power cue, a note of hope everywhere on earth…[ref]Howard Fast, Being Red (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990), 18-19.[/ref]

Whether Fast’s claim about Yankee Doodle was true could not be confirmed, but in 1943 he was the primary writer and editor of Voice of America news.

As for myself, during all my tenure there [VOA] I refused to go into anti-Soviet or anti-Communist propaganda.[ref]Howard Fast, Being Red (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990), 23.[/ref]

During World War II, VOA engaged in a massive coverup of Stalinist crimes and atrocities and would continue limited censorship in favor of the Kremlin until several years after the war. This changed only in response to strong criticism from members of Congress when new journalists, most of them refugees from communism, replaced pro-Soviet writers and editors hired during the war by VOA’s first director John Houseman.

Fast’s and Houseman‘s bosses–OWI director Elmer Davis and Robert E. Sherwood–were close to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his wife Eleanore Roosevelt. Sherwood, a Hollywood playwright, was FDR’s speechwriter.

The pro-Soviet propaganda activities these OWI officials originated and engaged in had a definite effect on FDR’s policy toward Russia, as well as on American perceptions of the Soviet Union and Joseph Stalin. By withholding information about Stalin’s atrocities from foreign audiences and Americans, these idealistic but extremely naive pro-Soviet American propagandists helped to minimize any initial opposition in the United States to Soviet control of East-Central Europe and the establishment of communist regimes in the region.

While the Soviet military presence was a decisive factor for keeping East-Central Europe under Moscow’s domination, Soviet propaganda and disinformation contributed to President Roosevelt’s unnecessary concessions at wartime conferences at Tehran (1943) and Yalta (1945) and to his willingness to believe in Stalin’s deceptive promises. This in turn facilitated the establishment of pro-Soviet communist regimes in the region and paved the way for Cold War conflicts in Korea and Vietnam.

Howard Fast resigned from his job at the Voice of America in January 1944 to devote himself to his work for the Communist Party, which he left only after Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev in his 1956 initially secret speech revealed some of Stalin’s crimes. As a journalist, Fast was embarrassingly naive, but he was hardly the only such person and journalist in the United States. In 1956 he was shocked by Khrushchev’s speech, but he never wavered in his support for socialism and the post-Stalin leadership in the Kremlin.

In the anthology, Red Diapers: Growing Up in the Communist Left, published in 1998, Howard Fast’s daughter, Rachel Fast Ben-Avi, wrote:

People at the Office of War Information, where he worked, drew him and my mother into the Cultural Section of the Communist Party.[ref]Fast Ben-Avi, Rachel. “A Memoir” in Red Diapers: Growing Up in the Communist Left, edited by Judy Kaplan and Linn Shapiro (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 126.[/ref]

She observed that her parents devoted themselves to the Party for the next twelve years and it became their entire life.

Rachel Fast Ben-Avi recalled that the Roosevelts had invited her father and mother to a luncheon at the White House on January 19, 1945. Her father, she pointed out, was famous and admired, and “Eleanor Roosevelt loved his books.”[ref]Fast Ben-Avi, Rachel. “A Memoir” in Red Diapers: Growing Up in the Communist Left, edited by Judy Kaplan and Linn Shapiro (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 126.[/ref]

Whether the Roosevelts knew that by then Howard Fast was already a Communist Party member could not be established.

Fast’s daughter also wrote about gifts of food and alcohol sent to their family by various embassies of communist countries and being invited to their diplomatic receptions. One of the gifts received from the Soviet Consulate, which Fast gave to his daughter, was a framed picture of Stalin holding children in his arms. She also recalled her father being under FBI surveillance in the 1950s and his three-month federal prison sentence after being found guilty of contempt of Congress. Because of his communist sympathies and support for the Soviet Union, Fast was also blacklisted in Hollywood for several years.

Rachel Fast Ben-Avi was present at the ceremony during which her father received his 1953 Stalin Peace Prize in New York City on April 22, 1954. The Stalin Peace Prize was later renamed retroactively Lenin Peace Prize so it can be said that the former Voice of America chief news writer and editor Howard Fast was the winner of both Stalin and Lenin Peace Prizes. W.E.B. Du Bois, an American civil rights activist, presented the award to Fast in 1954 when it was still the Stalin Prize.

Years later, Fast’s daughter wondered how his father could have not known about Stalin’s many crimes, including the fate of family friends, Russian Jews who had “disappeared into the Soviet Union, never to be heard from again.”[ref]Fast Ben-Avi, Rachel. “A Memoir” in Red Diapers: Growing Up in the Communist Left, edited by Judy Kaplan and Linn Shapiro (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 133.[/ref]

But she also presents him as a father who possessed “obvious goodness.”[ref]Fast Ben-Avi, Rachel. “A Memoir” in Red Diapers: Growing Up in the Communist Left, edited by Judy Kaplan and Linn Shapiro (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 126.[/ref]